China during the Song Dynasty witnessed unprecedented baby booms as the empire’s population crossed the 100-million mark for the first time. Economic and cultural prosperity obviously created favorable environment for the empire’s offspring, valued as carriers of bloodlines and bearers of fortune.

Genre paintings featuring happy young kids graced Song art across the Northern and Southern eras. Children at Play on the Winter’s Day is one of the best-known works by imperial academy artist Su Hanchen.

Besides pet cats, Song juniors weren’t short of toy options, either. Records identified the Chinese word for “toy” to be originated right in this dynasty when a toy market culminated and matured. Such toy stories were documented in Children at Play in an Autumn Garden, also painted by Su Hanchen.

Explore

3D model

Spinning wheel

with figures on horseback

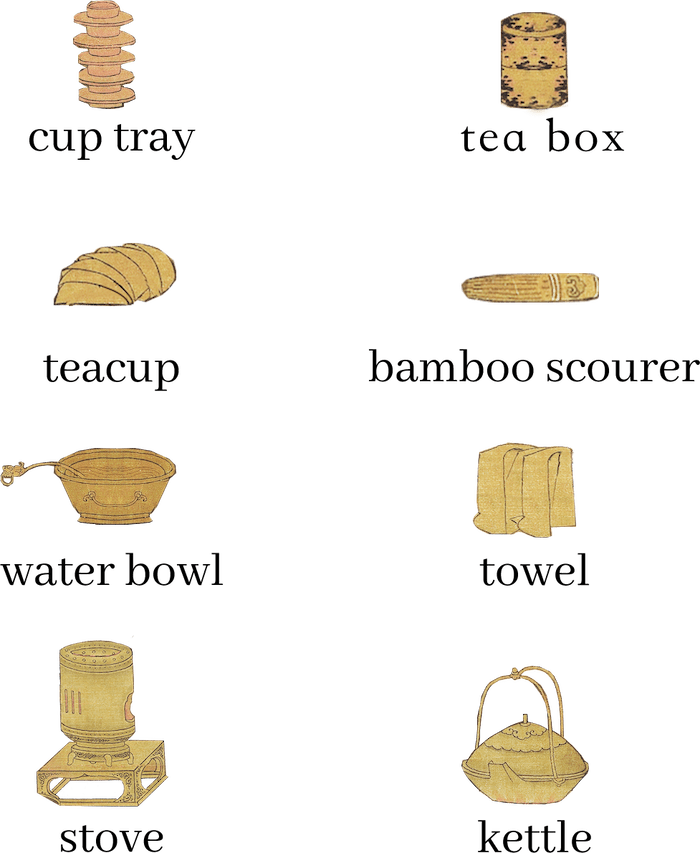

Tea culture in China reached a peak during the Song Dynasty. From nobles to peddlers, drinking tea was a popular pastime for everyone. Tea houses were all over town and sophisticated tea skills, etiquettes and related activities were subject matters in genre art.

The Water Mill at the Dam painted a panoramic picture of a state-owned milling workshop in operation and a nearby liquor shop where people enjoyed a drink as travelers and laborers went about their days. It’s a realist work that shows a scene of urban commerce and early industrial development during the Song Dynasty.

On the right side of the riverbank stands a tall liquor house, featuring a sign that reads “New Arrivals” and a banner hanging on the gate’s tower. Customers can be seen on the upper floor, while outside, busy laborers hustle by.

Between the mill and the tavern, cattle wagons carrying goods cross a bridge. Land and water transport developed tremendously during the Song Dynasty.

Goods were usually delivered on wheelbarrows and flat carts. The materials and end products used in the mill and at the pub required logistics that combined manpower and vehicles.

The levigator on the left powers the heavy revolving stone to grind the grain into flour.

The giant strainer on the right sieves the flour into finer powder ready for consumption. Thanks to this device, the rotation of the water-powered wheel is translated into linear motion that repeats itself back and forth, filtering bigger grains into smaller particles. Later literature such as Agro-Book by Wang Zhen of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) would high tribute to such mechanical innovations for greater and faster output.

“A play of Zaju might be funny,

You come with nothing and go empty.”

—— A poem by Wu Qian, Southern Song official

Zaju was an assorted show with comedic, musical and dramatic acting on stage. It became a popular form of theatrical entertainment during the densely populated and culturally sophisticated Song Dynasty.

Most Zaju plays were farce-style funny yet with Song Chinese folk humor.

Eye Drug for Sale is believed to be a poster promoting an upcoming Zaju comic show, or alternately as a household pin-up for private viewing. Painted on a silk square of 24cm x 24cm, it reminds the highly developed scene of theatrical culture of that time.

The advertised Zaju play would feature a drug-selling practitioner to be teased and challenged by a purported patient seeking eye treatment.

The “doctor” wears a sky-pointing black hat, carries a large drug bag and adorns himself with a dozen eye patterns all over his outfit. The middle-aged customer, dressed in court errand costume and holding a sign fan reading “jest,” points to his own eye complaining disorders but actually intends to make tricks of the charlatan doctor.

Playing Flower-drum portrays two Zaju entertainers saluting each other in fist-and-palm gestures. Their costumes, flowery head ornaments, earrings and foot sizes are evidently feminine.

Actresses made up a large chunk of Zaju performing artists during the Song Dynasty, cast to play male characters very often. Record books show at least half of the 72 leading performing artists acclaimed on the capital’s opera stage in late Northern Song were female, reflecting the popularity of pop divas of that time.

“Without half a speck of skin or flesh,

But carrying a load of suffering and sorrow,

A marionette himself, he still is pulling strings,

Manipulating a small model of himself to have his foes stay close.”

--“Heaven as Seen When Drunk” by Huang Gongwang, Yuan Dynasty artist

Explore

3D model

Chinese puppetry Kuilei was documented to have originated in the Han Dynasty (202 BC-AD 220), picked up in the Tang (618-907) before reaching new heights in the Song. Popular among both imperial and civilian audiences, Song-style puppetry plays, stringed or rod-driven, nurtured generations of performers and story titles.

Skeleton Puppet Play, by Southern Song painter Li Song, features a skeleton-shaped devil pulling multiple strings attached to the joints of a smaller skeleton, reminding how sophisticatedly puppetry craftsmanship and performance had developed in his time.

The painting on silk should originally be attached to a near-round fan with trace of a vertical axis. The big skeleton ghost, on the left half, with a breastfeeding woman behind him, manipulates the little skeleton in the center, across which a young lady stands and her toddler son crawling on the ground.

Thin apparels on the big skeleton and toddler suggest warm weather conditions so experts inferred that the artwork was probably created for the early summer Dragon Boat Festival in an implied theme of warding off evil spirits.

The skeletons should represent ghosts but here the big devil, quite an artist, even equipped with a musical instrument, seems to be teasing the toddler with fun instead of horror. The fine distinction between death and life was insightfully addressed in Taoist and Buddhist philosophical creeds of the time.

“Though an age-inherited ritual,

the Nuo looks more theatrical.”

--Zhu Xi, Song Neo-Confucian philosopher

Aesthetical tastes meant so much in Song China that people’s beautifying efforts would start from their headdresses. Seated Portrait of Song Renzong’s Empress shows two servants each wearing a black hat adorned with blossoms of peach, apricot, lotus, chrysanthemum and plum.

Such Song signature head ornament was aptly dubbed as “a full year’s sceneries” as it displays a kaleidoscope of all seasons’ floral beauties.

Men in that era would also wear floral headdresses, which reflected highly developed horticultural market selling fashionable accessories

Song cosmetics became less vibrant and more au naturel as women followed the time’s philosophical and cultural preference for noble grace and natural subtlety. Their makeup routine became more sophisticated thanks to enriched variety of substances. From base foundation to layer application, a whole set of cosmetic skills were developed fashionably and adopted widely.

A trendy style of eyebrow Song ladies would pick was Daoyun, whereby the outer edge of the arched strips would be smudged and gradually fade from dark to light to create a misty effect.

Women still preferred face beauty radiating from a foundation with white powder applied before adding rouge for a rosy complexion. Three more white patches were also purposefully painted on the forehead, chin and bridge of the nose.

Aristocratic women in the Song carried on the makeup use of pearls from earlier times to manifest lofty status and graceful demeanor. Resplendent pearls could be commonly seen on their foreheads, temples and cheeks.

Dubbed “lip-rouge” or “mouth-rouge,” red on lips was essential for women of the Song, sometimes mixed with a bit ochre, added with aromatics.

Song China’s connoisseurship for refined elegance affected people’s apparels. A signature pattern is Beizi, a long-sleeved outerwear worn by both men and women for centuries.

Women’s Beizi featured narrow sleeves, parallel collars that ran the length of the robe and slits on both sides. In Enjoying the Moon on Terrace, all three noble ladies are robed with knee-length Beizi, paired with a long skirt, slightly exposing undergarments.

The Beizi was made in fine geometric patterns and motifs of plants and animals. The most distinctive style would feature flowers characteristic of all four seasons. These ornamental elements generally appeared on the fabric itself or the hem.

Explore

3D model

The Palace Orchestra Rehearsal depicts scenes of performances and rehearsals by female court entertainers in the Southern Song. All the maids are dressed in red Beizi embellished with small flower patterns.

The Beizi would vary in style to cater to different situations. Women working in the process of raising silkworms and weaving silk as depicted in the painting Sericulture sport shorter robes made with light fabric. Casual and loose-fitting robes practically allowed them to move freely.

“Investigate things and deepen self-awareness”

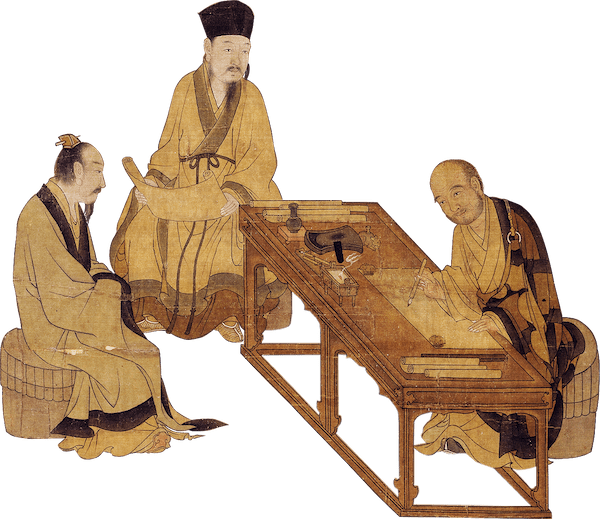

The reverence for the past among the Song intelligentsia is reflected in their pursuit of friendship with fellow literati. The Zither Player Rests as the Ruan Player Strums portrays two scholars sitting in nature,

Stop playing and find a friend. In the case of the painting "Listening to the Qin", which was painted by Zhao Ji-zong of the Song Dynasty and titled "One Man in the world", the music of the qin implies that the emperor guided and his subjects followed it

"Listening to the Qin" in the form of a vertical axis, the three main figures and the stone house, east, west, north and south four directions, almost in the shape of a cross

Corresponding angles. The composition of people and objects in the painting is concise and balanced, vaguely revealing a unique rigor and incompatibility in the context of Chinese painting

As the monarch, Huizong played the piano and his court officials listened to him, which actually showed that under the leadership of the monarch, the court officials were in harmony and propriety

A state of clarity. Huizong nominated "listening to qin" rather than "playing the qin", which emphasized that the emperor's "moral voice" could be accepted by

Xuan aficionado who lives in the north, the champions league, center sits, is bei song himself.

The bronze tripod, covered with verdigris, was placed on the exquisite stones and regarded as an ancient bronze ware.

The person wearing the red official robe has a higher rank, holds the fan low head, calmly listens to the music with respect. Some scholars believe that the red robe was CAI Jing.

The bronze tripod, covered with verdigris, was placed on the exquisite stones and regarded as an ancient bronze ware. One of the broken branches of flowers in the tripod entered the water, and several small white flowers blossomed on the branches.

Wearing green official robes of lower rank, cage sleeve back, slightly forward, respectful manner, appreciate the music.

The Song literati spared no effort in networking, sharing poems, artworks, tea, incense and flowers – all tasteful symbols or lofty items associated with the intellectual class.

Genre paintings featuring happy young kids graced Song art across the Northern and Southern eras. Children at Play on the Winter’s Day is one of the best-known works by imperial academy artist Su Hanchen.

Household affection for cats is visible from Song’s “children at play” paintings in which the plump pets pose playfully along with their young lords. Cats were often adopted as new family members with gifts for their previous owners in exchange.

Though the Scholars of the Liuli Hall depicts a gathering of poets in the earlier Tang Dynasty (618-907), similar parties involving intellectual elites were common throughout ancient China. Paintings of historical tales reflect the admiration that the Song people had for scholars of earlier times, as well the arts and crafts from bygone eras. The famous “Literati Gatherings at the West Garden” featured large numbers of the intelligentsia who interacted with poems, songs, calligraphy and paintings and shared an appreciation for the style of greats from the past.

China experienced progressive synthesis of Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism during the Song Dynasty. People tended to meditate Chan (Zen) for enlightenment, practice Taoist principles for healthy living and adopt Confucianism for social order. Worshippers would entrust the supernatural with their wishes in return for votive offerings.

Guanyin

of a Thousand Arms and Eyes

is one of many Song Dynasty paintings

depicting the bodhisattva of compassion,

who extends 1,000 hands to lift

mortal beings from suffering, and opens an

eye in the middle of each palm to look

after the human world.

Everything

with form is unreal—— The Diamond Sutra

The dragon in ancient Chinese mythology is a divine beast with supernatural powers and

a caretaker sent from Heaven, flying between Earth and

the sky, bringing with it

wind and rain.

The Nine Songs of Qu

Yuan depicts the dragon

in its auspicious glory,

breaking through the

clouds and radiating with might.

Ancient Chinese longed for immortality and sought all means to achieve it.

Song people’s reverence for Gods and belief in cause and effect led them to restrict their behavior in the hope of a tolerable afterlife.

Illustrated in the above painting is the fifth kingdom ruled by Yanluo.

The Yejing, or Mirror of Deeds, reflects the behavior of a dead person during their life.

Yanluo makes a fair judgment and issues his verdict before passing the spirit on to the next kingdom.

All lifetime wrongs

will be fairly reflected in the

Mirror at Hell

Variations of the Ten Kings of Hell painting were normally hung next to a Ksitigarbha statue in the confession hall of a temple to remind people of karma.

null

null