Editor's note: Guy Burton is an assistant professor at Vesalius College, Brussels. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The Brazilian political system was thrown into disarray last Sunday and it could lead to wider problems across the region. The investigative media website, The Intercept, published an archive of conversations which revealed the efforts the judicial system went to interfere in the political process. chief among those accused is the current Justice Minister Sergio Moro, who became famous as the judge at the center of the "Operation Carwash" scandal.

Operation Carwash was a money laundering investigation which began in 2014 and then began investigating corruption at Brazil’s state oil company, Petrobrás. The scheme involved executives pocketing bribes in exchange for large construction contracts. It sucked in politicians from across the political spectrum, including the then governing Workers' Party.

Among those caught up were former Presidents Dilma Rousseff and Lula. Rousseff had chaired the Petrobrás board during Lula’s two terms as president, between 2003 and 2010, before herself becoming president in 2011. Although she claimed to have no knowledge of the corruption which took place, the public was unconvinced. She was subsequently impeached and forced out of office in 2016 in the wake of a severe recession and on an unrelated charge.

That same year, Lula was questioned about his involvement in the corruption scandal. In 2017 he was prosecuted for accepting a triplex from Petrobrás and was convicted. He appealed the decision, during which time he became the favorite for the 2018 presidential election. In April, the court upheld his conviction and extended the sentence to 12 years, with Moro ordering him to prison.

With Lula out of the race, the far-right populist, Jair Bolsonaro, took the lead in the polls and won the election in October. One of his first appointees was Moro as his justice minister.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro (C) attends a ceremony to commemorate the participation of Brazil in World War II in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, May 8, 2019. /VCG Photo

The Intercept alleges that Telegram chats took place between Moro and the chief prosecutor in the investigation, Deltan Dallagnol. Moro is accused of not behaving impartially, as is expected, and instead offering advice and suggestions to Dallagnol over how to advance the case. Among the other criticisms made of the judiciary concerns the evidence used against Lula: that it was neither clear that Lula owned the triplex nor that it came from Petrobrás.

For now, President Bolsonaro has not defended Moro. On June 11, the two men met, but when he was asked to comment by the media at a public event, he cut questions short. A parliamentary inquiry has been set up, which Moro will attend, as well as the Senate’s constitutional and judicial committee. He is also trying to shore up support in Congress. Lula’s lawyers have moved quickly, with the Supreme Court to review whether Lula was wrongfully detained on June 25.

Bolsonaro’s silence indicates the extent to which he is under siege both in Congress and the country. Since taking office in January, he has had difficulty building a governing coalition to support his legislative agenda in Congress. He also has one of the lowest approval ratings for any president six months into office, following Brazil’s return to democracy in 1985.

In April, a Datafolha survey found that two-thirds expected a better performance and just over half were satisfied with the government. His education minister resigned while in May there were large protests by university students and teachers against the ministry’s decision to cut spending in federal universities by 30 percent. By contrast, pro-government demonstrations have been much smaller.

The implications of the Intercept allegations are several. The most immediate is that it risks politicizing the judicial system. This is ironic since it was under the Workers' Party governments that effort was put into improving the quality of the system, by building up the autonomy and capacity of the police and judiciary, with more financial investment. For the left, Lula’s conviction and Rousseff’s impeachment showed that the judiciary was working to its political agenda and bias; the exposure of the Moro-Dallagnol conversations will only confirm that view.

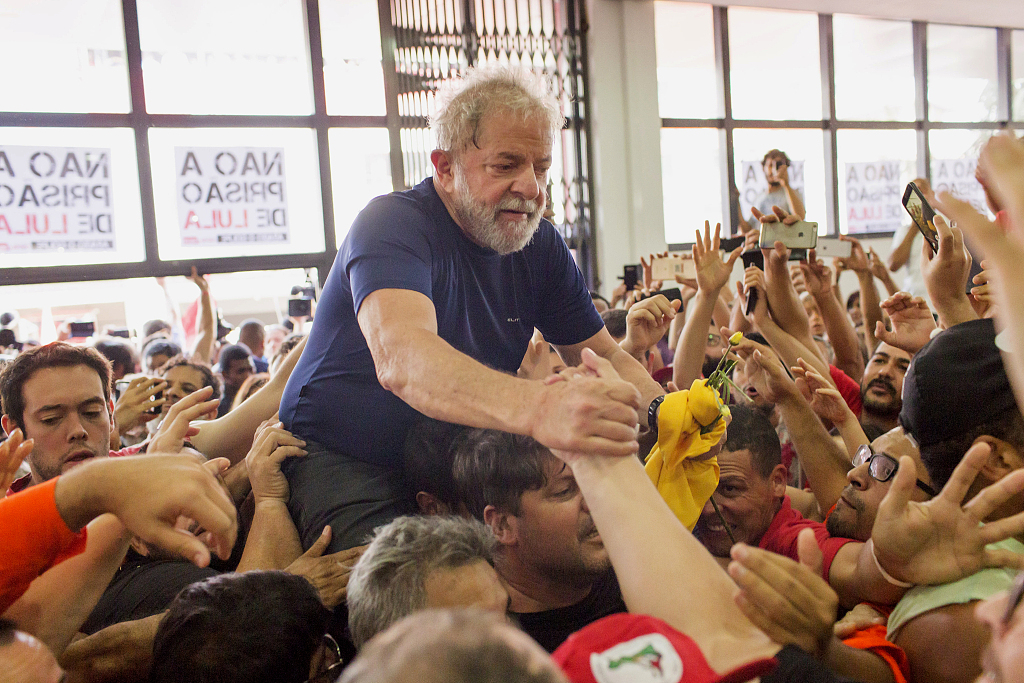

Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, Brazil's former president, greets supporters inside the headquarters of the Workers' Party in Sao Bernardo do Campo, Brazil, April 7, 2018. /VCG Photo

More broadly, the revelations may only exacerbate already declining support for the political system. Bolsonaro’s victory was only the most visible manifestation of this crisis. Latinobarómetro, which surveys public attitudes across Latin America, reported a sizable fall in support for democracy in Brazil in its latest report, published late last year. When asked if they agreed with the statement that democracy is the best form of government, 81 percent of surveyed Brazilians agreed; by 2018 this had fallen to 56 percent. In addition, 17 percent of the Brazilians surveyed in 2018 said the country was not a democracy, which was above the regional average of 14 percent, but behind Venezuela (37 percent) and Nicaragua (35 percent).

The loss of public support for the political system is not only felt in Brazil. Latinobarómetro reports a general malaise for democracy in Latin America as a whole – if not to the same extent as in Brazil. In the same five-year period, 2013-18, the number of Latin Americans who declared themselves satisfied with democracy fell from 79 percent to 65 percent.

While the reasons for such disillusion are varied, the Moro scandal in Brazil may only compound that frustration. Although Operation Carwash began in Brazil, it developed and escalated to take into account corruption across several other countries in the region, from Peru to Mexico to Colombia and Argentina. Particularly notable and tragic was former Peruvian President Alan Garcia’s suicide in April, when the police came to arrest him.

The revelations associated with the Moro scandal may be seized upon by societies in those countries as they ask themselves whether the same could be happening there. As Brian Winter, the editor of Americas Quarterly, pointed out, this may have implications for not only those watching the news, but involved in those investigations: "Many prosecutors doing their own hard work [will] feel betrayed [by the exposures because] they know they will be accused of bias [and] impropriety."

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3