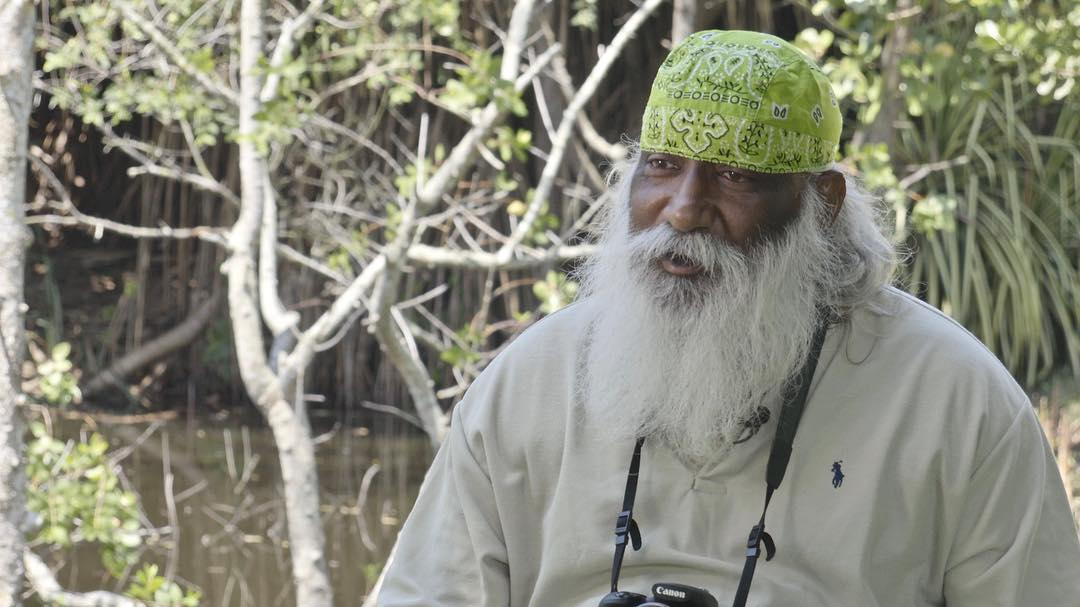

Subaraj Rajathurai has been a wildlife consultant for over 30 years. /CGTN Photo

"Now that we are moving more and more into natural areas and homes are being built on the edge of reserves, we must be more tolerant and be able to live in harmony with nature. Otherwise there is only going to be one winner and it is not going to be wildlife," Subaraj Rajathurai, a Singapore-based wildlife consultant, said in a firm warning.

Singapore's impressive transformation from a squatter colony to a cosmopolitan city and developed economy in a single generation is one of Asia's biggest success stories.

Unfortunately, this success has come at the cost of the city-state losing some of its natural habitats and wildlife.

As its population continues to grow, tropical rainforests and wetlands have been giving way to offices and apartment complexes.

As Subaraj Rajathurai, who runs Strix Wildlife Consultancy explains, "rainforests are down to about 3% of what was here, mangroves may be about 2%, so you can see its very small numbers and some of them are broken up into fragments."

Rajathurai adds that the reduction in the native fauna has resulted in the disappearance of one-third of the country's native animals in just a matter of 30 years.

Many animals have paid the price. We have lost many habitats down to the very last bits of it. And as a result, some of the animals that are more specialized to forest areas or mangroves, they've actually disappeared from the island."

Rajathurai breaks down the numbers.

"We have lost maybe about 30 percent of the mammals that were once found in Singapore. For freshwater fish, we have lost about 40 percent, birds may be close to 20 percent."

Natural habitats making way for the urbanization. /CGTN Photo

However, there are some animals who have successfully managed to adapt and move from their natural habitats to man-made ones.

"It is a small percentage of the biodiversity that is able to adapt very well. Some of them have foregone their specialty and become more adaptable," says Rajathurai.

An excellent example of the animals that have not only adapted but managed to thrive and grow in the urban environment are Singapore's otters.

"The smooth-coated otter has always been riverine. They depend on the rivers and mangroves. And here we do not have a lot of that and a lot of our rivers have been made into reservoirs and canals and somehow they have managed to find a way to survive," says Rajathurai.

In fact, the now famous and tourist favorite otters have been spotted across Singapore, making appearances at the Botanic Gardens, splashing in the Singapore river, and swimming about in the Central business district.

"They are going into underground canals, rivers. They have been moving underground. And amazingly are now found in most parts of the island. They are fish eaters by large. Our reservoirs are stocked with fish, so they have the food."

Otters are spotted splashing about in Botanic Gardens ponds. /CGTN Video

Rajathurai shared with us that in 1990, there was just one recorded otter in Singapore. That number has now expanded to an estimated 70 otters in the city-state.

The return of otters in Singapore is being seen by many observers as an amazing example of cohabitation between people and wildlife.

But Rajathurai warns that "there are other animals that still require special habitats that are fast disappearing and they need us to protect them in nature reserves and nature parks."

He adds that "today we have places like Pulau Ubin protecting mangroves but there is such a high demand for those small areas that the animals are still being impacted upon rather than being allowed a way to come back."

Rajathurai believes that in order to preserve the ecosystem and avoid isolating some species, there is a strong need to have better connectivity between the fragmented areas.

"We are trying to connect them, the different fragments of the genetic pools. The ecolink is a good example. But we need more of those."

The "Ecolink" that Rajathurai refers to is an ecological corridor or an overpass built especially for wildlife to pass between fragmented habitats.

Singapore which prides itself as a Garden city, has been focusing on a wide range of efforts to protect the native flora and fauna.

The Wildlife Reserves Singapore Conservation Fund (WRSCF) was established in 2009 with the primary purpose of conserving Singapore's endangered native wildlife.

To date, WRSCF has supported over 30 projects on the conservation and research of species that include the endangered banded leaf monkey, the elusive leopard cat, long-tailed macaques, coral reef restoration, local butterflies, amphibians, reptiles, and freshwater crabs.

As Rajathurai puts it, ultimately it is all about maintaining a balance between conservation and development. And the onus is not just on the authorities, but on the general public as well.

"We use nature reserves and nature parks as multi-use areas also for recreation and exercise. When people go in and abuse that privilege, playing loud music and going in huge groups, those are the things that belong in a park, they don't belong in Bukit Timah or MacRitchie Reservoir."

"I think we need to show our nature reserves a little more respect rather than treat them like neighborhood parks," he adds.

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3