Editor's note: Sun Hong is an associate research fellow at the Institute of African Studies of the China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations. The article reflects the author's views, and not necessarily those of CGTN.

This week from June 18 to 21, Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, gathers 11 African heads of state and over 1,000 business leaders from the U.S and the continent to attend the 12th U.S.-Africa business summit. This event is regarded as one the most important mechanisms for U.S.-African relations, or at least economic cooperation. This gathering gives us an opportunity to examine Trump’s newly-formulated Africa policy.

Last December, John Bolton revealed the Trump administration’s Africa Strategy, in which the focus is misplaced on competition with China. The strategy announced that the U.S. government will divert existing limited resources in Africa to contend with China for economic influence.

This year, the new nominee for U.S. AFRICOM Commander, Gen. Stephen Townsend, claimed bluntly that China would pose a threat to U.S. national security interests in Africa. In the meantime, senior U.S. officials and Congressmen made groundless accusations of China’s Belt and Road Initiative dragging African countries into a debt trap. It is out of this mentality that the new Africa policy is formulated, where economy is rising to top priority, while anti-terrorism and promotion of democracy is being downgraded.

Strengthening economic relations

The U.S. government has been airing grievances for not getting high returns from its annual 9 billion U.S. dollars of aid channeled to the continent. Scholars also lament that the U.S. has lost ground to geopolitical competitors, like China, in the region. In 2016, Africa accounted for 1.5 percent of the total U.S. exports, while it made up 4.2 percent of the Chinese export market. Against this backdrop, Trump administration is determined to expand economic influence on the continent.

Pineapples in Soyo, September 29, 2017. /VCG Photo

On one hand, efforts to provide official support for the private sector are stepped up. Since assuming office, the Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, Tibor Nagy, has traveled to a dozen African countries to promote U.S.-Africa economic relations, setting the record as the official who has traveled the most to the continent for any first year in office.

In October 2018, Trump signed the bi-partisan BUILD Act into law. This Act establishes the International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC) as the main development finance institution to encourage U.S. companies to fully explore markets in low and lower-middle income countries, especially those in Africa.

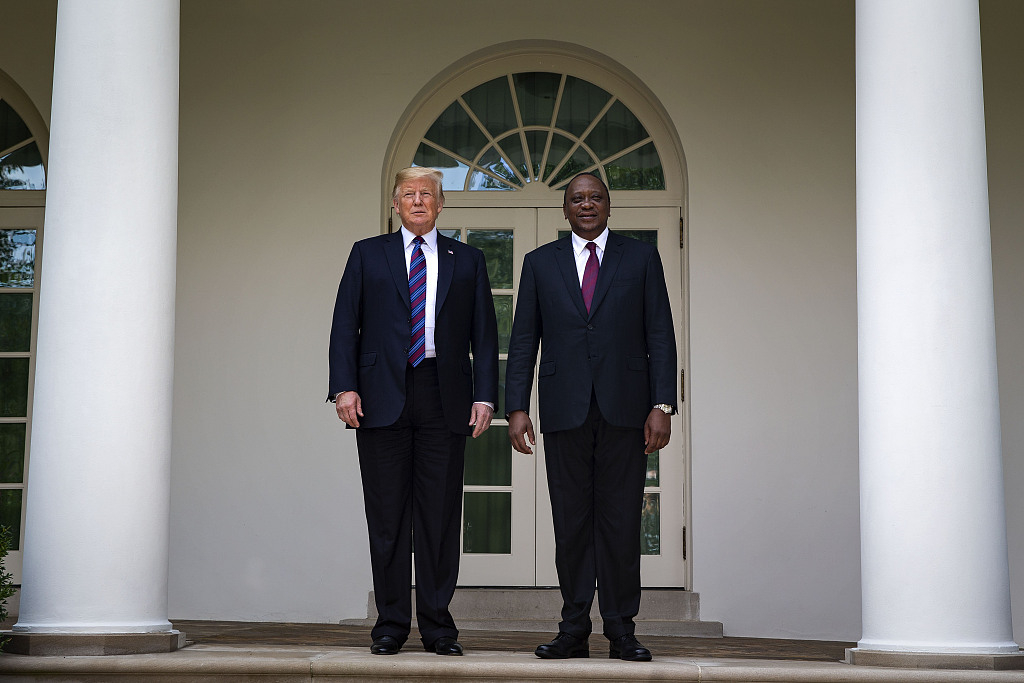

On the other hand, the U.S. also eyes stronger economic partnership with certain countries, especially those with rapid growth, mature business environment or strategic importance. Kenya, Ethiopia, Ivory Coast, Mozambique, to name just a few, are countries on its radar. For example, during his first official meeting with Trump, President Kenyatta inked deals worth 900 million U.S. dollars.

Cutting security and democracy input

It was made clear by an official that Pentagon’s decision to withdraw 10 percent of the troops of the current 7,200 stationed in Africa is to focus on countering the so-called threat from China and Russia.

Another distinct rupture from his predecessor is that Trump is not so passionate about intervening in African countries’ domestic affairs in the name of promotion of western democracy, free and fair elections, etc.

U.S. President Donald Trump and Uhuru Kenyatta, Kenya's president, meet at the West Wing colonnade of the White House in Washington, DC, August 27, 2018. /VCG Photo

Take the presidential election in Democratic Republic of Congo, for example. Though the influential Catholic Church and other observers deem the election “rigged” and the opposition leader Martin Fayulu should have been the winner, the U.S. government, unlike its previous style, took a hands-off approach and endorsed the results. Some even criticized that Trump supported Guaido in Venezuela but abandoned Fayulu.

Time to recalibrate

Trump’s Africa policy will bring about positive changes for Africa in terms of economic development. The newly-founded IDFC will contribute to filling the infrastructure financing gap, accelerating local industrialization, and creating more jobs for African youth. However, the U.S. government should be reminded that Africa is not a “prize” to race after, nor a battlefield where major powers could carry out geographic competition.

The groundless and untenable accusations that China drags African countries into a “debt trap” will only irritate both China and African countries and deteriorate the business environment which will in the end hurt the interests of everyone. According to much research, the largest creditor of most African countries is west-dominated multilateral financial institutions.

The African continent is big enough for every sincere partner, including China and the U.S. It’s meaningless and against the interest of African people to see each other through a zero-sum lens. As an old Chinese saying goes, if you want to go fast, go alone; if you want to go far, go together. Considering the good records of China-U.S. cooperation in areas like public health, especially co-combating the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2015, there’s a good chance for the two powers to make greater contributions to African development rather than making enemies.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3