By any measure, the barriers to reproductive health in the world's poorest nations remain particularly acute, 25 years after the International Conference on Population and Development sought to re-engineer the debate about population growth.

Until that momentous Cairo meeting, the population focus was on numbers, but delegates agreed that the conversation should be steered toward social, economic and political equality, including sexual and reproductive health and rights, as this would better promote individual well-being and sustainable development.

A program of action was developed that encompassed such areas as safe pregnancy, childbirth services, family planning and prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections.

The thinking was that enhancing individual health and rights would eventually lead to lower fertility and slow population growth – a topic that gains worldwide attention annually on World Population Day (July 11).

But while some progress has been made, reproductive health remains a severe challenge for the world's least developed countries (LDCs).

A look at the latest available United Nations statistics gives an indication of the scale of the problem.

The UNFPA says its aim is "to ensure that every pregnancy is wanted, every childbirth is safe and every young person's potential is fulfilled." /VCG Photo

In 2015, the maternity mortality ratio (deaths of women from causes related to pregnancy and childbirth) was 12 per 100,000 live births in the planet's richest nations. In LDCs the number rose to 436.

The bottom line is that 99 percent of all maternal deaths occur in developing countries – not all of which are LDCs, according to the World Health Organization.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where more than half the deaths occur, a number of countries have halved their levels of maternal mortality since 1990, the WHO says. In other regions, including Asia and North Africa, even greater headway has been made.

Between 1990 and 2015, the global maternal mortality ratio dropped by only 2.3 percent per year, though the decline has accelerated since 2000. Yet that 40 percent or so cumulative reduction was well below the 75 percent envisaged in the Cairo declaration.

Access to contraception

The 2015 average was at 216 per 100,000 live births, down from 385 in 1990. One of the global sustainable development goals is to bring it down to 70 by 2030.

The vision of reproductive health embodied in the Egyptian capital was not only that every birth should be healthy, but that every pregnancy should be intended and every sex act should be free of coercion and infection – a roadmap that even developed nations find hard to fully meet. Factors such as education and cultural practices like child marriage and female genital mutilation also impact on reproductive health.

For an issue like contraception, the gap between rich and poor is as stark as the maternal health ratio. The contraceptive prevalence rate for women aged 15-49 who are married or in a union is currently estimated to be at 68 percent among MDCs, according to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Among LDCs, the figure is 42 percent as against the global average of 63 percent.

Here is a sample of other relevant statistics:

• Teenage birth rate per 1,000 women aged 15 to 19, 2006-2017: MDCs 14, LDCs 91.

• Secondary school enrolment, net percentage of female secondary school-age children, 2017: MDCs 93%, LDCs 36%.

• Total fertility rate, per woman, 2017: MDCs 1.7, LDCs 3.9 (global average 2.5).

A lot of these issues arise because women living in poverty around the world are exposed to greater health risks and cannot pay for healthcare and adequate nutrition.

Funding an issue

The situation isn't helped by a lack of access to good information and services to protect women's reproductive health – including control over the number and timing of children.

The global efforts to minimize the risks to reproductive health are continuing. For instance, the WHO says improving maternal health is one of its key priorities as it works to contribute to the reduction of maternal mortality by increasing research evidence, providing evidence-based clinical and programmatic guidance, setting global standards, and providing technical support to member states.

Funding for all these efforts has, however, not kept pace with need. And in more recent times, the United States has dealt a severe blow to the global reproductive health program by withdrawing financing from UNFPA, which focuses on family planning as well as maternal and child health in more than 150 countries.

The U.S., then the fourth largest donor, said two years ago that it was dropping funding because UNFPA "supports, or participates in the management of, a program of coercive abortion or involuntary sterilization."

The agency rejected the claim as erroneous saying its mission is "to ensure that every pregnancy is wanted, every childbirth is safe and every young person's potential is fulfilled."

It is a mission that must be supported if women's health and rights are to reach full potential around the world.

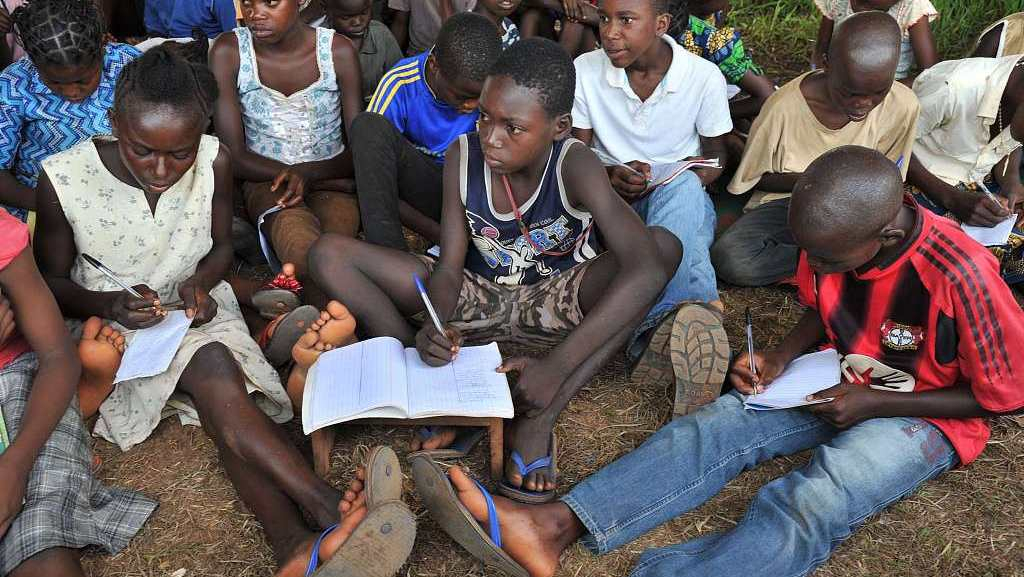

Top Photo: A girl writes in a notebook as she attended a class in a tent, used as a temporary classroom, on February 6, 2014, on the Saint-Marc Grand Seminary site in Bimbo, southwest of Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic where thousands of internally displaced were housed. /VCG Photo

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3