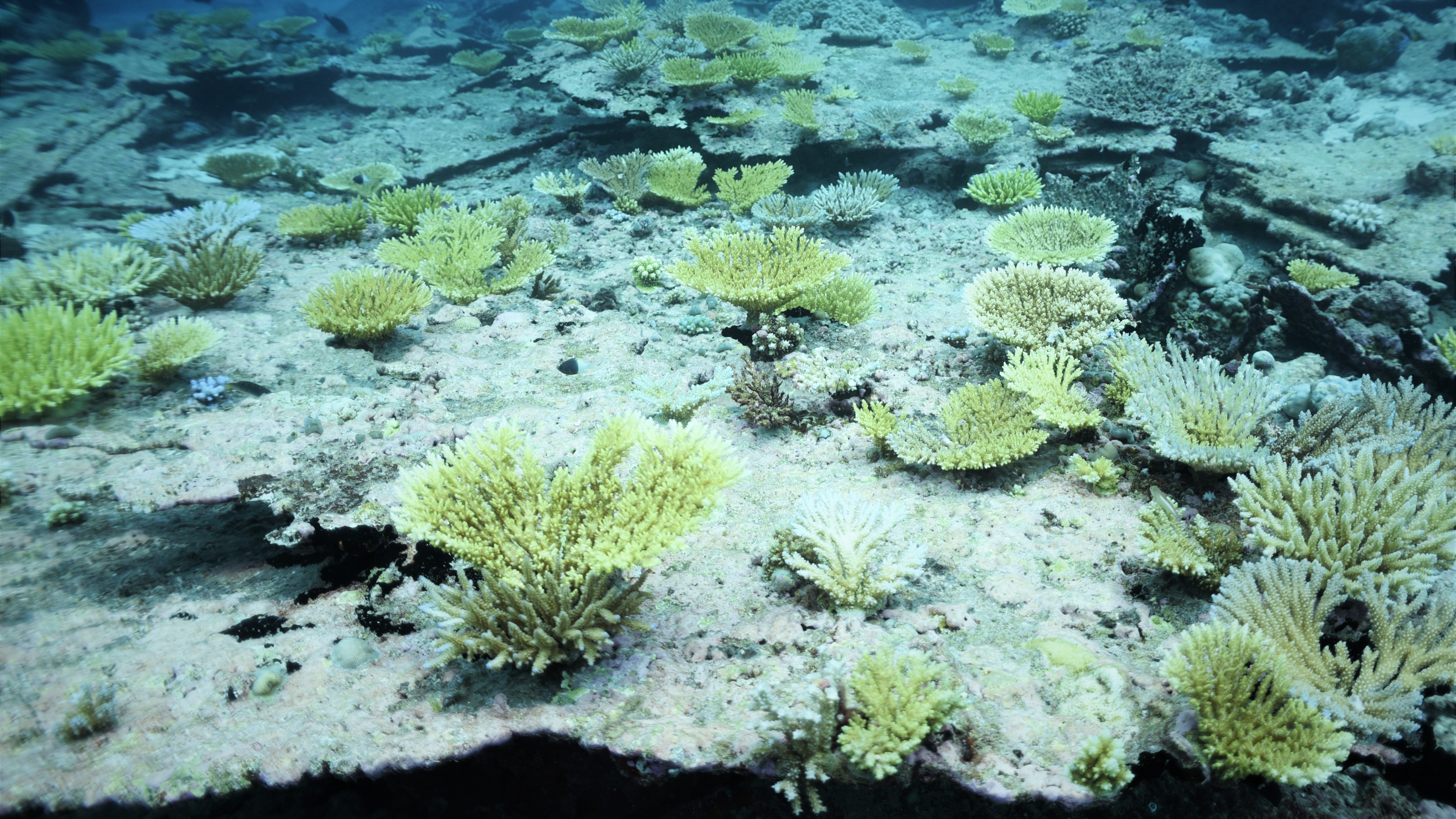

A young coral reef regrowing in British Indian Ocean Territory. /ZSL Photo

Two extreme heatwaves within one year killed nearly 70 percent of corals in the central Indian Ocean, a study released Friday said.

The scorching sun increased the seawater temperature for eight weeks in 2015, affecting nearly 60 percent of hard corals within the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) at depths of up to 10 meters.

For some species – including the Acropora corals known for providing habitat to gastropods, fish, turtles and lobsters – the damage was much more significant, with high temperatures killing 86 percent of them.

In 2016, another heatwave spell lasting for over four months bleached 68 percent of the remaining hard corals. As a result, 29 percent of them died. Surveys carried out in 2015 and 2017 found that “approximately 70 percent of hard corals were lost,” researchers said.

Coral reefs, an underwater structure formed by marine animals, occupy barely 0.1 percent of the ocean area but protect coastlines of more than a hundred countries from seawater rise.

The structure also provides habitat to more than 25 percent of all marine species existing on the planet. Global warming, changing ocean chemistry and mining are some of the leading causes behind its destruction.

“We know it has taken about 10 years for these reefs [in BIOT] to recover in the past but, with global temperatures rising, severe heatwaves are becoming a more regular occurrence, which will hinder the reef’s ability to bounce back,” Dr. Catherine Head, the study's lead author, said.

In order to quantify the scale of the destruction, researchers from the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) compared data on the coral reef in BIOT waters before and after the heatwave.

The findings published today in the journal Coral Reefs also found that the second heatwave caused fewer casualties despite lasting longer.

The resilience of the remaining corals to rising temperatures and their ability to endure and regenerate may be key to protecting reefs from climate change-induced rises in sea temperatures, researchers mentioned.

“It is encouraging that reefs may have some degree of natural resilience, though further research is needed to understand the mechanisms by which some corals are able to protect themselves,” Head added.

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3