Editor's note: James Rae is a director of Asian Studies at California State University in Sacramento, California, U.S. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Japan has launched a direct assault on the South Korean economy with its reducing exports of valuable chemicals used in the high technology sector. Why did Japan do this, and where do bilateral relations go between the two large Northeast Asian countries?

To find the answer, we must begin a century ago during Imperial Japan's colonial occupation of Korea that lasted from 1910 to 1945.

Among the crimes committed under Japanese rule was the use of perhaps millions as forced labor generally and compelling tens of thousands of women to serve as military sexual slaves specifically.

Those victims began to demand acknowledgment, compensation, and apologies from the contemporary Japanese government, and despite their age, organized more directly through legal and social channels starting in the 1990s.

In winter 2018, alongside growing support from South Korean President Moon Jae-in, the S. Korean Supreme Court ruled in favor of the victims in their lawsuit against Japanese companies. The Japanese government had tried to claim that it formerly settled all such claims when it provided some financial aid and loans (less than 1 billion U.S. dollars) to the Korean government in 1965, and more recently in arranging a voluntary compensation fund for survivors while eschewing official responsibility in both instances.

Embarrassed by its World War II behavior but unwilling to satisfy long-standing demands for greater accountability and worried that these issues might persist and even grow, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has raised the stakes in cutting off these chemical components, which are essential for smartphones, televisions, and semi-conductors.

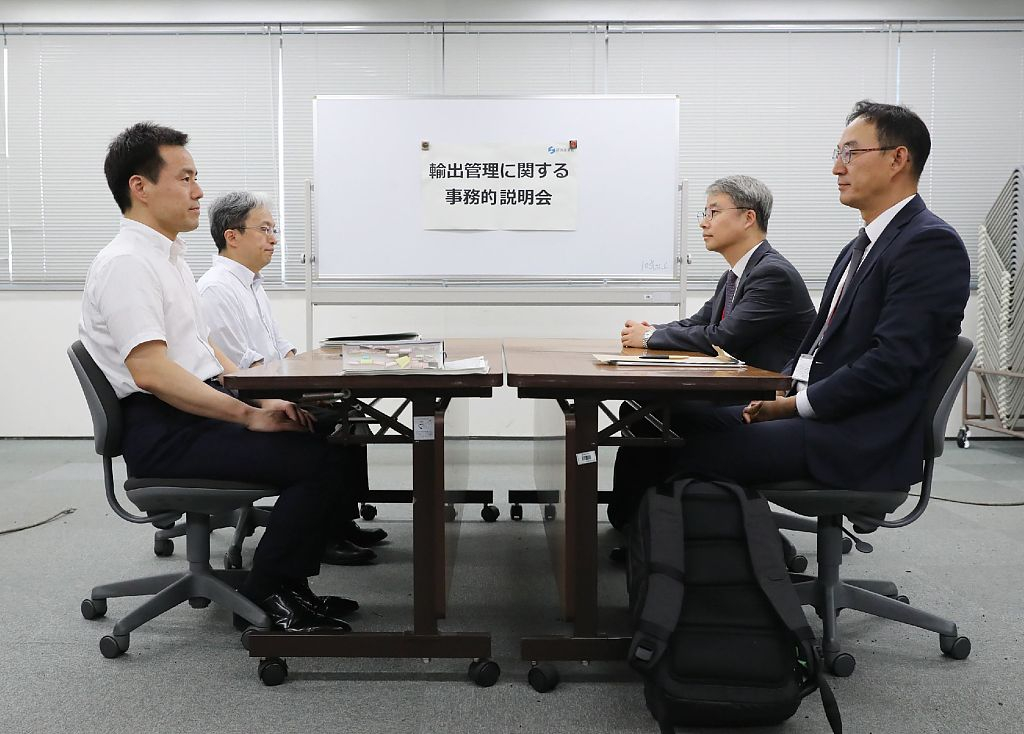

A director (Front L) of trade control policy division at Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) holds a meeting with South Korean officers (R) on the imposed restrictions in Tokyo, July 12, 2019. /VCG Photo

Of course, the United States has partially normalized pursuing self-aggrandizing national interests through trade policy, and so Japan's behavior may be only a symptom of the new global economic environment.

In that regard, it risks undermining the relatively harmonious economic relationship between Japan and South Korea, and indeed the burgeoning positive trade ties among Asian markets reflected in the recent G20 summit in Osaka where Japan and China expressed a keen interest in furthering cooperation and regional integration.

Those goals are on hold while we see if Seoul and Tokyo can walk back this dispute and either settle the issue of forced labor or set it aside and emphasize the opportunities for positive-sum outcomes by delinking the human rights issue from trade.

Steps have been taken in both directions. On the one hand, S. Korea, Japan, and the United States are preparing for an opportunity to have a trilateral dialogue and indeed are pursuing diplomatic talks behind the scenes.

Moreover, China has resuscitated the regional free-trade talks among the three countries alongside the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). In an era of American economic protectionism, each of the three countries has a strong incentive to pursue regional cooperation, particularly China.

At the same time, Japan has resisted South Korean calls for inviting the United States to be a third party mediator and has reiterated its confidence that the export control regime is sound and valid, and may indeed have a national security rationale owing to a suspicion that some of the chemicals made their way into DPRK.

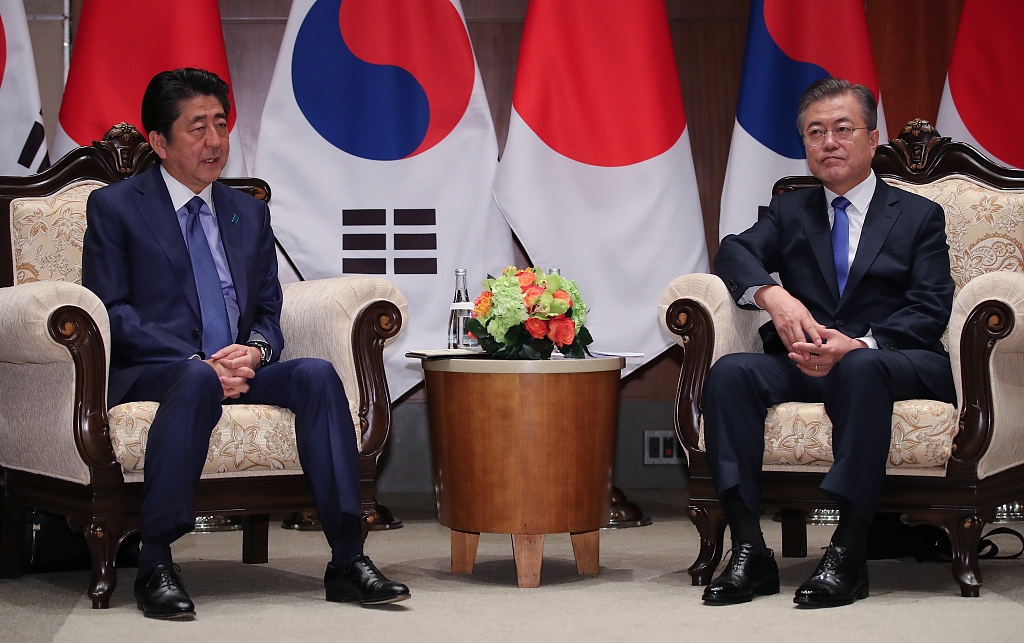

Moon Jae-in, the President of the Republic of Korea, meets with Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in New York, the U.S., September 25, 2018. /VCG Photo

In response, President Moon is advocating building a domestic supply chain for these rare chemicals while also calling for an international investigation into these highly suspect allegations that such materials were diverted to DPRK or even Iran. South Korea may also pursue a claim against Japan at the World Trade Organization (WTO).

All of this brings us back to the fundamental issue of Japan's wartime atrocities. If the victims' lawsuit was dismissed or President Moon disowned the victims' position, Japan would likely reciprocate and withdraw its new standards on export controls and return to the over-a-decade-long approach of offering S. Korea preferential treatment on these chemical compounds.

Not only is that politically risky for President Moon, and likely out of his hands, it demeans the legitimate claims of those very elderly and very real victims. It is also true that Japan has issued apologies, has arranged private funds to provide welfare for such victims across Asia and has provided aid and trade to help develop East Asian economies.

Perhaps the best hope is to leave the highly sensitive issues of historical memory and wartime accountability (along with island disputes, textbook controversies, and the like) to one political track, and keep the economic track moving harmoniously based on shared commercial interests.

For if the global supply chains are interrupted and East Asian regional economic ties fray, the potential for a global trade war where everyone loses only grows, and the glue that keeps the tenuous East Asian security environment together may weaken and come apart.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3