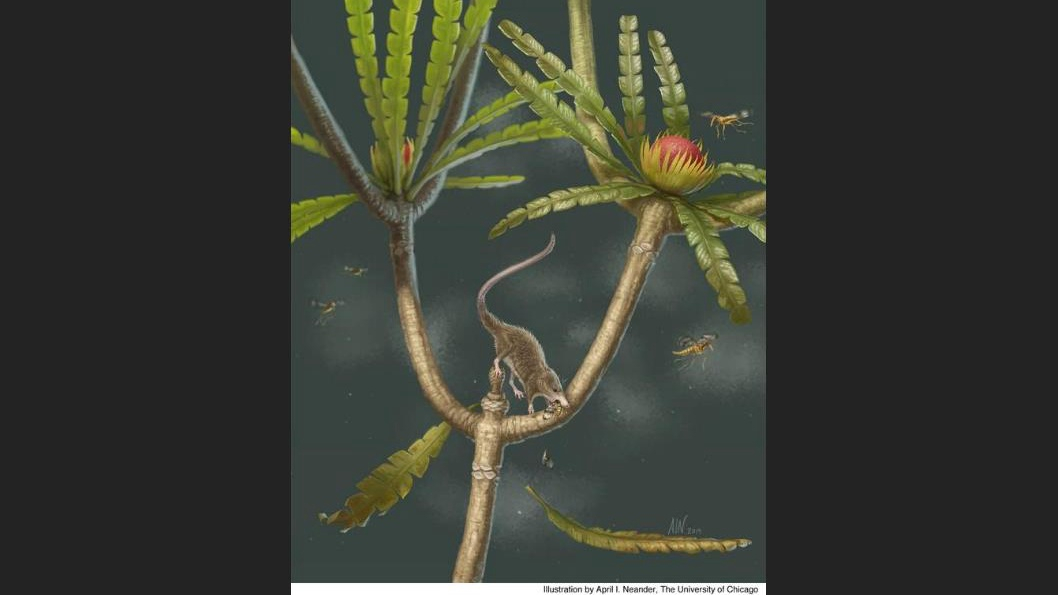

A life reconstruction of the newly-discovered primitive Jurassic mammal Microdocodon gracilis. /Reuters Photo

A shrew-like primitive mammal that inhabited China 165 million years ago represents a milestone in mammalian evolution, scientists said on Thursday, boasting a key anatomical trait in its throat that helped usher in the era of polite table manners.

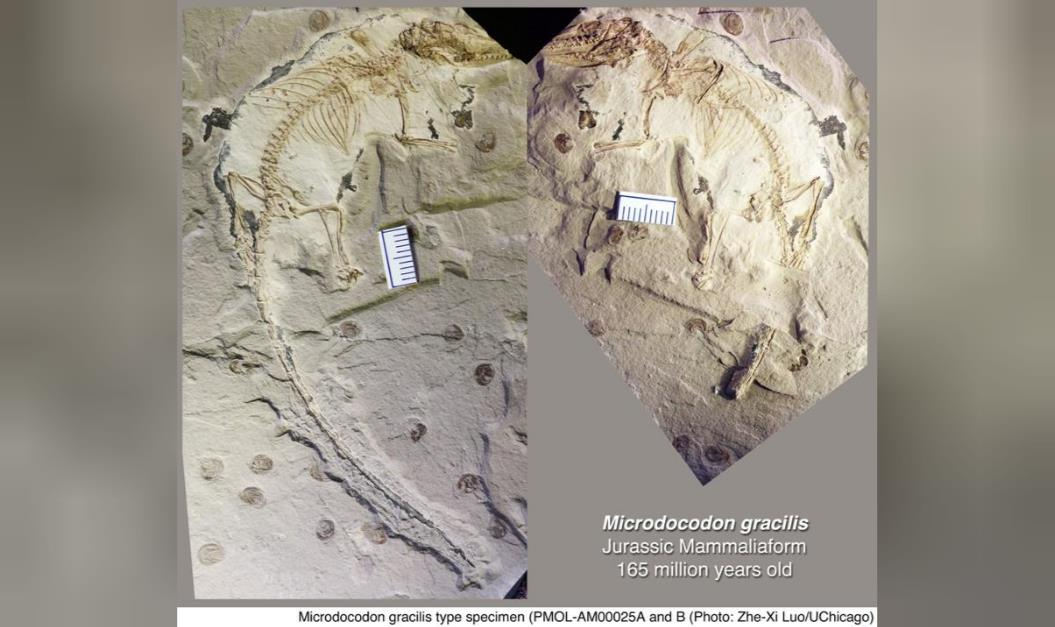

Scientists described an exquisitely preserved Jurassic Period fossil from Inner Mongolia of a furry critter called Microdocodon gracilis. It was a lightly built, long-tailed, insect-eating tree-dweller roughly five inches (14 cm) in length that lived in a warm lake shore environment alongside feathered dinosaurs and flying reptiles called pterosaurs.

Before Microdocodon, land vertebrates including amphibians, reptiles and predecessors to the mammalian lineage had resorted to gulping large chunks of food or swallowing prey whole, as crocodiles do today, relying largely on jaw strength or gravity to guide the meal down the throat. A revolutionary change present in Microdocodon's throat allowed for more finesse in muscle-powered swallowing and, thus, genteel dining.

The fossil of the newly-discovered primitive Jurassic mammal Microdocodon gracilis. /Reuters Photo

Microdocodon is the earliest-known creature whose hyoid bones in the throat are configured as in modern mammals. The delicate hyoids connect the back of the mouth, or pharynx, to the openings of the esophagus, which is the tube connecting the throat to the stomach, and the larynx, the "voice box" that provides an air passage to the lungs.

Unlike its evolutionary predecessors that possessed hyoids in a sturdy rod-like configuration, Microdocodon's hyoids had mobile joints and were arranged in a "U" shape that let it chew food in the mouth and then swallow it along with liquids one small lump at a time rather than in big, ungainly gulps.

"We, the mammals, distinguish ourselves from other vertebrates by chewing our food into tiny morsels for good digestion," said University of Chicago paleontologist Luo Zhexi, senior author of the research published in the journal Science. "The innovation to chew our food goes hand-in-hand with our sophisticated hyoid apparatus that enables us to swallow the chewed food, to drink water, and also for mammalian babies to suckle milk."

This apparatus for active swallowing apparently evolved in combination with the advent of complex teeth that let primitive mammals chew and then swallow this predigested food for more efficient energy intake, added University of Bonn paleontologist Thomas Martin, another senior author of the study.

Primitive mammals appeared during the Triassic Period roughly 210 million years ago. Mammals became Earth's dominant land animals after the dinosaurs were wiped out 66 million years ago by an asteroid impact.

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3