Editor's Note: Chris Deacon is a postgraduate researcher in politics and international relations at the University of London and previously worked as an international commercial lawyer. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

In elections for Japan's upper house held on July 21, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe's ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its allies were unable to win a super-majority, resulting in a major setback for Abe's plans to revise the constitution.

In Japan's bicameral political system, elections are held for both a lower house and an upper house, with the latter's elections being held every three years for two different sets of seats.

The seats up for grabs yesterday were last secured in 2013 when the LDP performed particularly well. Analysts, therefore, predicted that the party would not quite be able to match that performance and lose ground, as has come to fruition.

While it is generally the lower house that is considered to be the most important chamber, for some time now Abe has pursued reform to Japan's constitution, particularly in relation to the pacifist Article 9.

Revising the constitution requires a two-thirds super-majority in both the lower and upper houses, as well as simple majority approval in a public referendum.

The LDP has been in coalition with another party – the Komeito, associated with the lay Buddhist organization Soka Gakkai – although Abe would be more likely to be able to rely on the votes of other right-wing parties to support his proposed revisions.

Ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) executives watch a monitor displaying a news broadcast of the result of the upper house election at the party's headquarters in Tokyo, Japan, July 21, 2019. /VCG Photo

However, despite winning a clear majority in upper house elections, Abe and these partners were not able to win a two-thirds majority, as would be required to amend the constitution.

Given that Abe is only able to serve as prime minister until 2021 due to internal limits within his own party, this election was seen as a crucial test as to whether he would be able to proceed with the reforms. If he wishes to continue building a legacy for his premiership, as he seems intent to, Abe may need to rethink his plans.

It is possible, for example, that Abe might seek to water down his proposed constitutional changes so as to win the support of some opposition parties who are opposed to his current plans.

The Democratic Party for the People (DPP), for example, could be amenable to this. In Japan's current chaotic opposition politics, this party was created from the remnants of the short-lived Kibo no To (Party of Hope), set up by Tokyo governor Yuriko Koike.

This party would be much more likely to cooperate with Abe on this issue than the main opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan (CDPJ), which itself was formed out of the remnants of the Democratic Party of Japan when the party was split by the creation of the Party of Hope and – as its name suggests – is strongly opposed to Abe's planned revisions.

Even if Abe is able to win a super-majority across the lower and upper houses for revised plans, he will still have to contend with the prospect of a national referendum.

Currently, a clear majority for constitutional reform does not exist; although, it is certainly not impossible that public opinion could change, particularly if Abe's proposals are watered down.

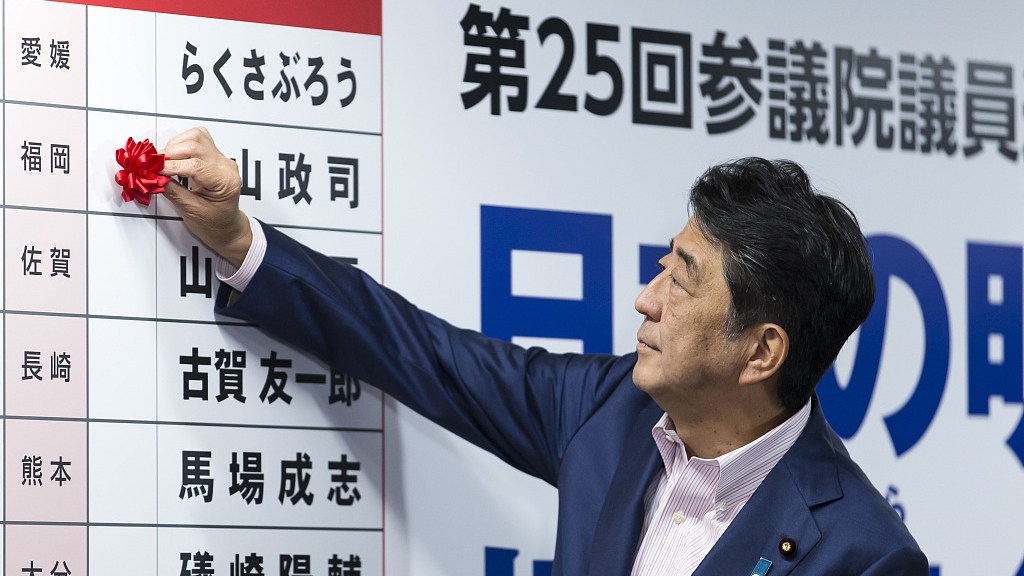

Japan's Prime Minister and ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) President Shinzo Abe (C) places a red paper rose on an LDP candidate's name to indicate an upper house election victory at the party's headquarters in Tokyo, Japan, July 21, 2019. /VCG Photo

Abe will be concerned, however, that he may gain "lame duck" status if he is blocked from pursuing one of his core political aims either by parliamentarians or public opinion.

In recent months, he appears to have strongly focused on building a foreign policy legacy, including, for example, reaching a resolution with Russia on the disputed Northern Territories and launching negotiations with DPRK leader Kim Jong Un. He may seek to increase the attention paid to these areas instead.

There is also the possibility that the LDP's internal rules could be revised to allow Abe to serve a further, fourth term as its leader and, provided the party's electoral success continues, as prime minister.

Indeed, the LDP's secretary general stated on July 21 that he believed, given the public's continued appetite for the party and Abe as its leader, it would not be "unnatural" for such a measure to take place.

This could give Abe more time to build support for his proposed constitutional revisions; however, these have been in discussion for some time now, and Abe has previously held the requisite majorities in both houses and yet not moved ahead.

There is also currently no reason to believe that public opinion would markedly change in the event of a longer Abe premiership.

For the time being, therefore, we wait to see Abe's next move on this issue for hints as to whether he still wishes to pursue his goal of revising the constitution. It would almost certainly be his dream legacy as prime minister, but it may remain just out of his grasp.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3