More than 8 million Guatemalans on Sunday voted in a second-round run-off election for a new president who is likely to face a major challenge coping with a deal signed with Washington in July to turn the country into a buffer zone to stem illegal immigration despite the endemic poverty and violence plaguing the Central American nation.

Election results are expected to begin arriving on Sunday night in what is expected to be a tight race.

Voters must choose between conservative Alejandro Giammattei and his center-left rival, former first lady Sandra Torres. Both veteran political campaigners have criticized the deal, but will probably be unable to do much to stop it.

Whoever takes office in January will inherit a country with a 60% poverty rate, widespread crime, and unemployment, which have led hundreds of thousands of Guatemalans to migrate north.

Honduran migrants, part of a caravan trying to reach the U.S., walk during a new leg of their travel in Chiquimula, Guatemala October 16, 2018. /Reuters Photo

"A lose-lose situation"

Threatened with economic sanctions if it said no, the outgoing government led by President Jimmy Morales signed an agreement to make Guatemala a so-called safe third country, meaning the U.S. can turn away asylum seekers who have passed through the Central American country without seeking refuge there.

The pact, part of U.S. President Donald Trump's campaign to stem migration at his country's southern border, has proved highly unpopular in Guatemala, with demonstrators blocking roads and occupying the emblematic University of San Carlos.

In a poll by Prodatos for the Prensa Libre newspaper, 82 percent of respondents opposed it.

A woman holds her son as she waits to get into Mexico, near the border gate between Guatemala and Mexico, in Tecun Uman, Guatemala, November 2, 2018. /Reuters Photo

The agreement was reached last month despite Guatemala's constitutional court granting an injunction blocking Morales from signing the deal.

Guatemala's human rights ombudsman Jordan Rodas questioned its legality, while Amnesty International described it as "cruel and illegal."

The deal would allow the U.S. to send some Honduran and Salvadoran asylum seekers who passed through Guatemala back to the poor, crime-stricken Central American country, an influx it is ill-prepared to receive.

Risa Grais-Targow, Latin America director at consultancy Eurasia Group, said the agreement would expose the country to the risk of tariffs on its goods or taxes on remittances, which account for 12 percent of the country's GDP according to the World Bank.

"The next president faces a lose-lose situation when it comes to managing the deal with the United States," she said. "That is the biggest challenge the incoming president faces."

A man runs in front of a campaign sign for Sandra Torres, presidential candidate for the National Unity of Hope (UNE), ahead of the second round run-off vote, in Guatemala City, Guatemala, August 10, 2019. /Reuters Photo

The Unpopular pair

Neither candidate has a glowing reputation, both having failed in previous bids for the presidency.

The center-left Torres, whose ex-husband Alvaro Colom was president from 2008-2012, has been suspected of involvement in corruption before.

Influential businessman Dionisio Gutierrez recently described her as "a questionable politician with a history that should worry any citizen."

Giammattei, a conservative, has hardly come off any better, with investigative website Nomada branding him as "impulsive... despotic, tyrannical... capricious, vindictive," among other undesirable traits.

But the 63-year-old, a doctor by profession, scores well on key voter concerns such as the economy, corruption and security.

A CID-Gallup opinion poll of 1,216 voters conducted between July 29 and August 5 gave Giammattei the advantage going into the run-off vote, with 39.5% support, versus 32.4% for Torres. The poll had a margin of error of 2.8 points.

Between them, the two candidates failed to win the presidency five times. Polling suggests that although Torres came out on top in a first found of voting in June, her unpopularity may prove her undoing.

"I wasn't going to vote, but ... seeing the circumstances I better vote so that Sandra doesn’t win," said Ricardo Son, an 84-year-old retiree in Guatemala City.

A women runs in front of a campaign signs for Alejandro Giammattei, presidential candidate of "Vamos" political party, ahead of the second round run-off vote, in Guatemala City, Guatemala, August 10, 2019. /Reuters Photo

Entrenched corruption

Both candidates have concentrated their campaigns on attacking entrenched corruption and promising to improve education and health care while investing in poorer areas to reduce poverty and discourage Guatemalans from seeking the "American dream."

Almost 60 percent of Guatemala's 17.7 million citizens live in poverty.

Combating gang violence is another major issue, with 2018 statistics putting the murder rate at 22.4 per 100,000 people, one of the highest in the world.

Around half the killings are blamed on drug trafficking and extortion operations carried out by powerful gangs.

Giammattei has proposed the death penalty for some criminals and promised to erect an "investment wall" on the border between Guatemala and Mexico to curb migration.

Torres wants to put troops on the streets to fight gangs and use welfare schemes to alleviate poverty, a strategy she supported as the first lady between 2008 and 2011.

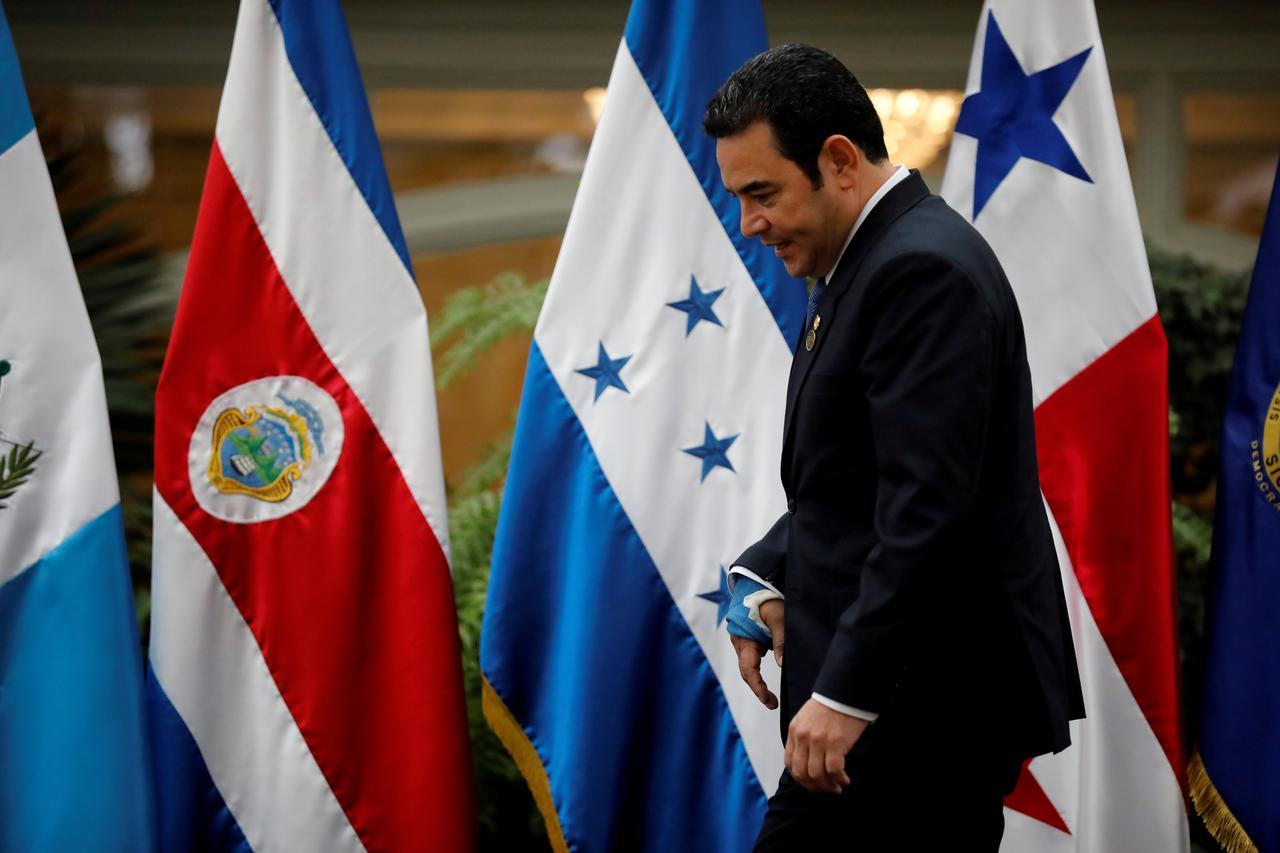

Guatemala's President Jimmy Morales is seen before a family photo during a meeting of the Central American Integration System (SICA), in Guatemala City, Guatemala, June 5, 2019. /Reuters Photo

Many Guatemalans are fed up with the political class after corruption scandals led to the arrest of former President Otto Perez in 2015 and then threatened to unseat his successor, incumbent President Jimmy Morales.

Both candidates have vowed to fight corruption without "foreign interference," an apparent allusion to the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), the United Nations mission that brought down Perez and went after Morales.

The CICIG mission is due to end in September and both presidential candidates have ruled out extending it, although they claim they will create special prosecution agencies to fight corruption.

Morales, who terminated the commission's mandate effective as of September, is barred by law from standing again. But his legacy could prove lasting if the migration deal he authorized becomes a defining feature of the next administration.

(With input from agencies)

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3