Over 100 lives are feared dead after a boat packed with migrants sank off the Libyan coast, the Medecins Sans Frontieres revealed on Tuesday, bringing the death toll of Mediterranean migrants to over 900 this year.

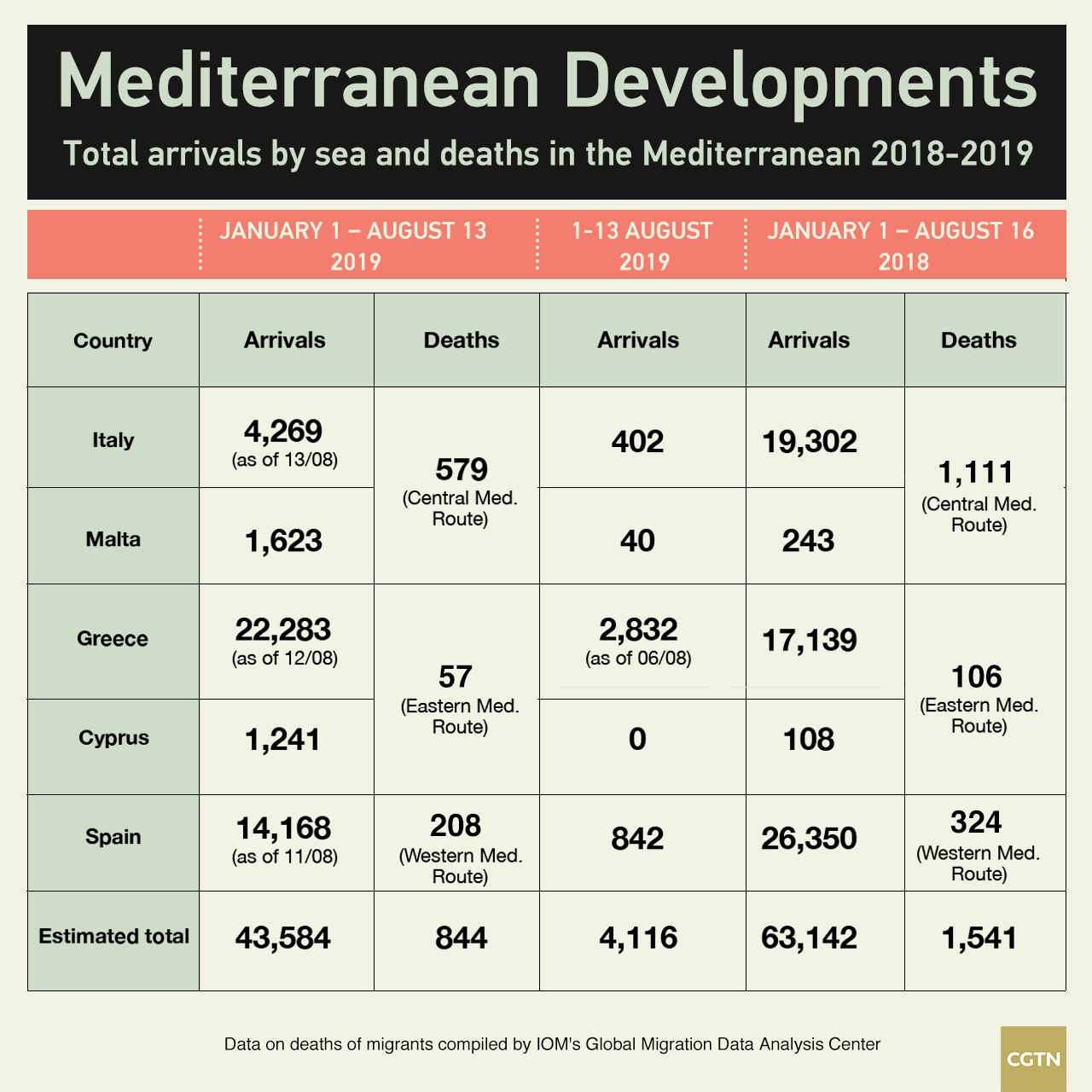

From January to August 13, 2019, 844 people died on the three main Mediterranean Sea routes, representing about 55 percent of the 1,541 deaths confirmed during the same period in 2018, reported the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Only last month, another boat carrying about 250 people, mainly from Eritrea and other sub-Saharan Africa and Arab countries, capsized off the coast near Komas, east of Tripoli. Libya Coast Guard and local fishermen rescued 134 people, while about 115 were missing.

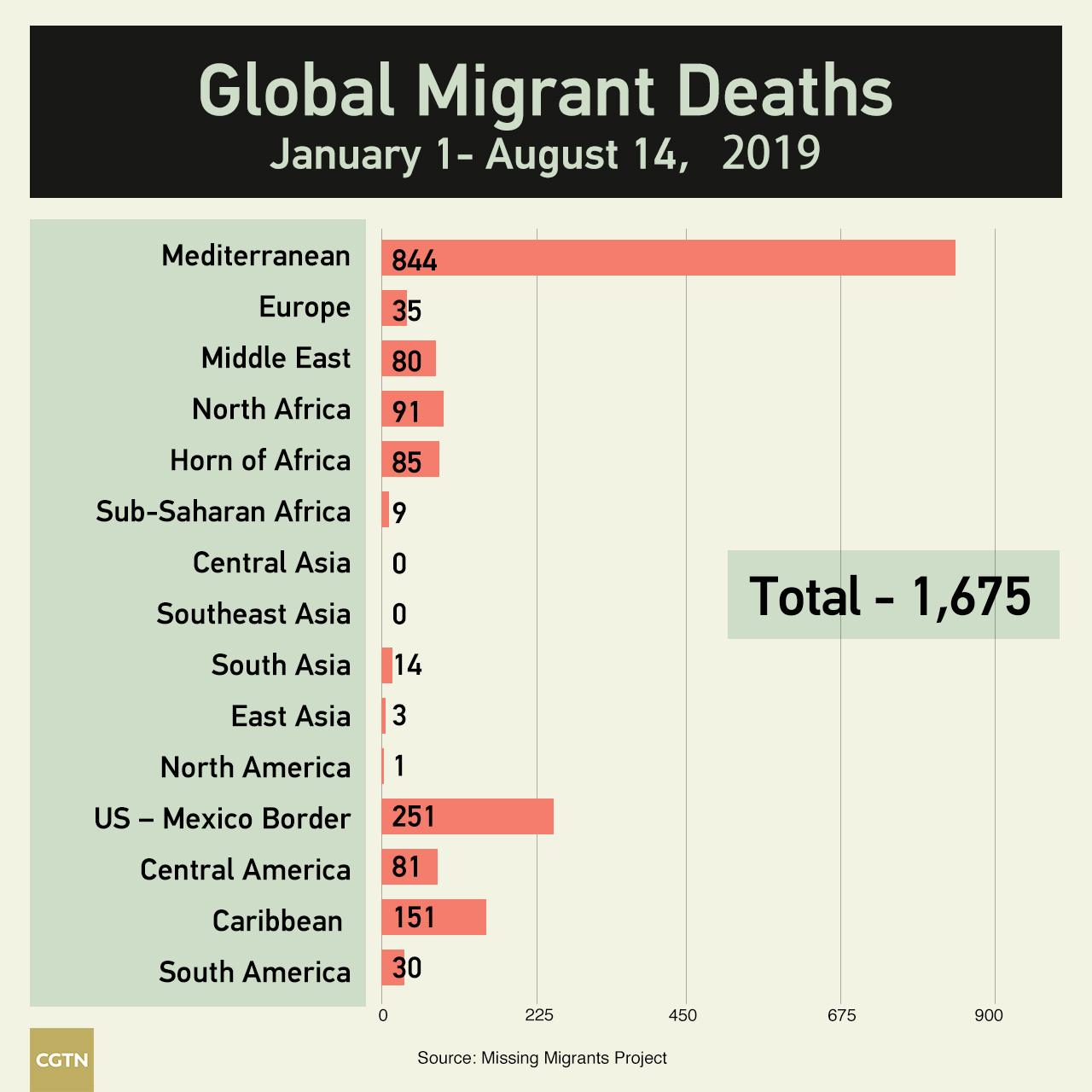

The Missing Migrants Project data from IOM based staff and the Global Migration Data Analysis Centre reports that drowning and hypothermia are the main causes of death in the Mediterranean. This year alone, 1,675 people died worldwide on route to what they hoped to be a better life.

IOM data indicates that 43,584 migrants and refugees have entered Europe by sea through August 13, roughly a 31 percent decrease from the 63,142 that arrived during the same period last year. Arrivals this year to Greece and Spain are at 22,283 and 14,168, respectively, accounting for almost 84 percent of the regional total, with the balance arriving in much smaller numbers to Italy, Malta, and Cyprus. Arrivals to Spain are about 46 percent lower.

The decrease in the number of deaths and arrivals isn't convincing to Vicki Squire, professor of International Politics at the University of Warwick and principal investigator in the project "Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by Boat" by mapping and documenting migratory journeys and experiences along key routes.

"Arrival figures are complex and what we currently see is shifting numbers on different routes to Europe as well as significant levels of deaths and arrivals – this remains unacceptable," said the scholar to CGTN Digital.

Squire explained that "one of the main reasons for reduced arrivals to the EU this year is the effort on the part of EU states to increase migration control operations beyond its shores, for example by supporting Libyan authorities to ‘rescue’ those at sea and return them there." But this, "essentially puts people at increased risk of harm and danger."

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Filippo Grandi, noted in a Euronews interview that investing in Libya "wouldn't be a bad thing" if it was done properly. Instead of trying to resolve the conflict and reconstruct the country, most of the resources are being allocated to the Coast Guard, which rescues the migrants and refugees at sea and sends them back to detention centers in Libya. These are mostly run by militias and not the authorities, noted the commissioner.

Reports of routine torture, rape, malnutrition, and diseases led the UN to call for the dismantling of all detention centers. In response, the Libyan government said it plans to shut down three of the biggest ones: Misrata, Tajoura, and Khoms.

Grandi admitted that Libyan camps are "so awful, and so dangerous, and so humiliating for people, that it is understandable" that people stranded there want to make a life-threatening journey across the sea.

The Salvini Decree and the 'growing homeless population'

The struggles of migrants and refugees worsened at the hands of Italy's far-right interior minister Matteo Salvini and his anti-immigration stance.

In December 2018, the "Salvini Decree" won a vote in the Italian parliament and was then formally endorsed by the president Sergio Mattarella. The bill abolishes humanitarian protection for those not eligible for refugee status but who cannot be sent home, including those with pending requests and permits to stay. This meant that people are forced to leave the welcome centers, becoming homeless. In January, the police demolished a camp near Rome with 500 people and on March 6 another one with around 1,500 people in Calabria, southern Italy.

Migrants wait to board a bus as they prepare to leave from the migrants center in Castelnuovo di Porto, north of Rome on January 23, 2019. Following the decision to close Italy's second largest migrant reception center. Vincenzo Pinto/VCG Photo

Vicki Squire was not able to say how many migrants become homeless following the minister's efforts to close down the centers. However, "what is clear is that many people are forced into precarious employment and face increased uncertainty about their future," she said.

In an article published in The Conversation, Squire says that at dusk, Termini station in central Rome comes alive with people lining in the pavement to sleep in the street. "The implications of Salvini’s actions are concerning, not only for 'migranti' who find themselves on the street but also for many Italians. A growing homeless population is not good for anybody," stated the scholar, noting that closing the centers also means fewer employment opportunities to local people.

"Salvini has a strong anti-migrant agenda and following and there is significant discontent among the Italian population regarding the EU's failure to show solidarity on migration issues. However, Salvini already faces significant criticism in Italy and it’s not clear he will be able to continue unabated," noted Squire to CGTN Digital.

The political crisis in the Italian government raises questions regarding the continuity of his anti-immigration policies. Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte resigned and attacked Salvini, accusing him of sinking the coalition and endangering the economy for personal and political gain.

Until then, Italian justice has taken a stance in some decisions. For example, a judge overturned Salvini's port closure and allowed an NGO search and rescue vessel to dock at Lampedusa.

This happened again on August 20, when Sicilian Prosecutor Luigi Patronaggio ordered that 83 migrants on board the Open Arms charity vessel must be disembarked. The rescue ship was anchored off the island of Lampedusa for 19 days, because it had been refused permission to dock by Salvini.

Lack of solidarity and ONG criminalization

In this case, before the judicial order and offer from Spain to receive the ship, France, Germany, Romania, Portugal, Spain, and Luxembourg said they would help relocate the migrants. Nevertheless, migrant issues, in general, have seen a lack of generosity from EU countries.

Spanish NGO Proactiva Open Arms rescue a woman in the Mediterranean open sea about 85 miles of the Libyan coast on July 17, 2018. Pau Barrena/ VCG Photo

"EU states could show greater solidarity not only with each other but also globally, in order to provide safe and legal routes for those in-flight who seek peace and safety," said Squire in line with Filippo Grandi. “In Europe, the race is about who does the least to accept these people and dealing with them rather than a race for generosity," stressed the UN Commissioner.

NGOs have also "faced increased criminalization across the EU and in particular in Italy," noted Squire. "This is a serious risk to civil liberties and a worrying trend that has not been challenged adequately by the EU," said the scholar.

Some NGOs were accused of fomenting or increasing trafficking when, according to Grandi, they play a significant role in the rescue mechanism in the Mediterranean.

In her research, Squire and her team discovered that for many migrants and refugees “destination Europe” is not a pull factor in their migration journey. They fled war or conflict, threats of terrorism or cult groups, kidnapping and torture or violence. Some of them were also sent to Europe against their wishes. Some fled to Libya to escape poverty, conflict, and persecution elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East only to find a war-torn country and the feeling that their only choice at survival is a perilous boat journey at the hands of smugglers.

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3