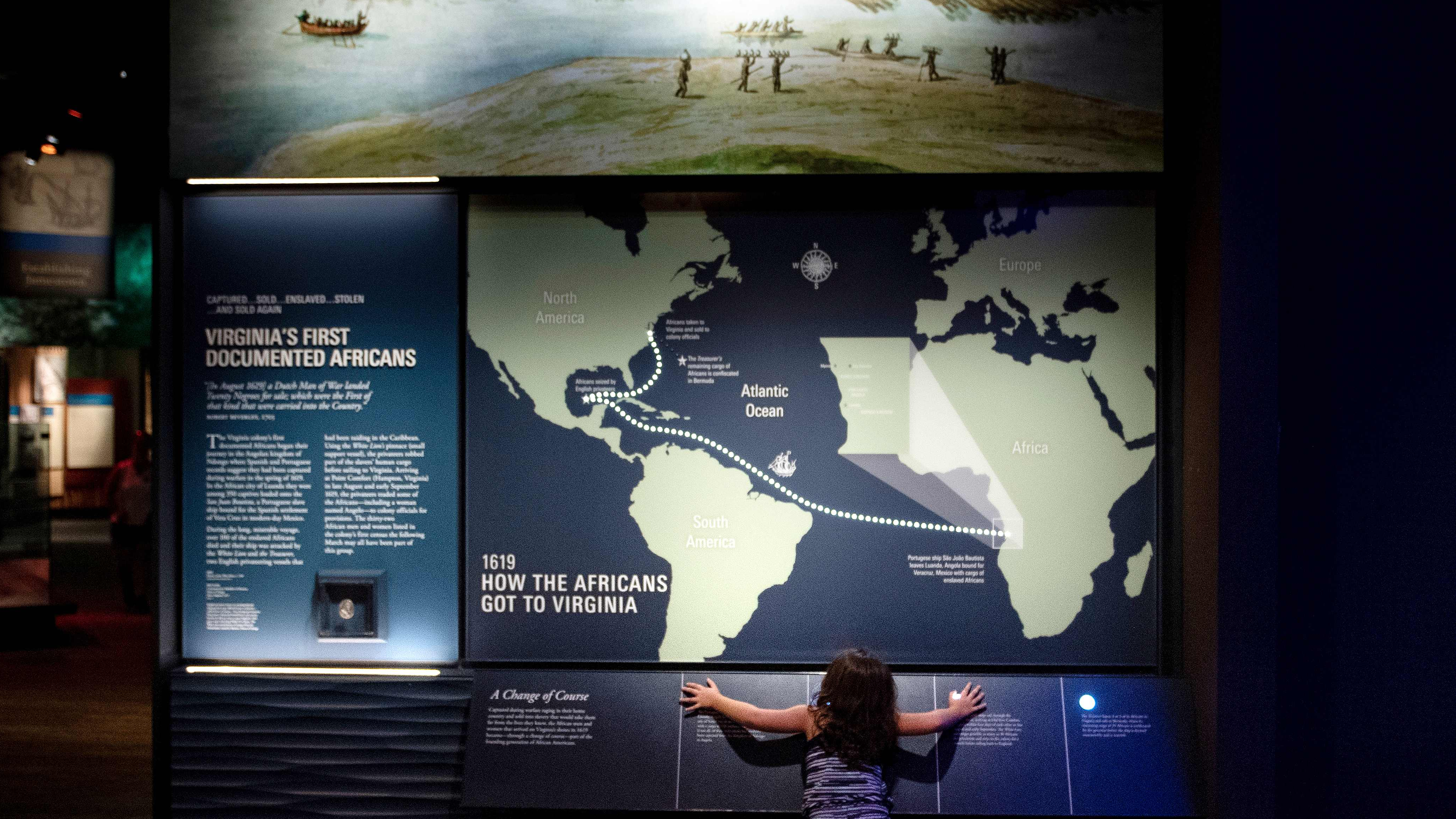

People view an exhibit about slavery at the historic Jamestown Settlement, in Williamsburg, Virginia, U.S. August 19, 2019. /AFP Photo

In an effort to remind the world of the painful history of slave trade, Ghana is commemorating the year 2019 as the "Year of Return" to remember the 400th anniversary of the first slave ship that crossed the Atlantic to reach North America in 1619.

The year-long program peaked this month ahead of the annual remembrance day for the abolition of the slave trade on August 23 with a string of prominent African Americans visiting a number of sites linked with slave trade history in the West African country.

A delegation of the U.S. Congressional Black Caucus led by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi took a tour of some of the prisons in Ghana last month that are euphemistically described as "slave forts."

There were 40 such prisons built by European – mainly Portuguese and Spanish – slave traders across the Ghanaian coast where African captives were held before being shipped to America.

Emerging from one such pitch-dark dungeon in Cape Coast Castle, Roxanne Caleb, an African American preacher couldn't stop tears rolling down her eyes as she told AFP: "I wasn't prepared for this. I'm heartbroken. My mind still can't wrap around the fact that a human being can treat another worse than a rat."

"This has been understanding my history and my roots where I came from. I am very thankful I came here as part of the Year of Return," she said.

The "Year of Return" has already resulted in a surge of visitors to Ghana, which has long championed itself as a destination for African Americans to connect with their roots and heritage.

Fishermen carry their nets at Cape Coast Castle, Ghana, as they walk down the same steps many enslaved Africans walked before they were loaded onto ships to be sailed across the Atlantic Ocean, August 18, 2019. /AFP Photo

The West African nation is hoping the numbers rise from 350,000 in 2018 to 500,000 visitors this year, including 45,000 African Americans. It is also expecting tourism revenue of 925 million U.S. dollars by the year-end.

"It's like a pilgrimage. This year we've [had] a lot more African-Americans coming through than the previous year. I'm urging all of them to come home and experience and reconnect to the motherland," Kojo Keelson, who has been conducting guided tours around the Cape Coast Castle, told AFP.

A decade ago, then U.S. president Barack Obama visited the Cape Coast Castle with his family and paid homage.

Angela, 'Eve' of African Americans

Meanwhile in the historic site of Jamestown in the U.S. state of Virginia – the first permanent English settlement in North America – archaeologists are working relentlessly to retrace the life of Angela, arguably the first documented African woman slave who arrived in North America in the first ships from West Africa in 1619.

The Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation in partnership with the National Park Service is excavating the historic site to learn more about Angela, who has been described as the "Eve" of enslaved Africans. The study so far has revealed that Angela was originally from the kingdom of Ndongo, in what is now Angola.

Angela, along with hundreds of other slaves, were loaded onto a Portuguese ship in Luanda which then headed to Veracruz, in the Spanish colony of modern-day Mexico. At the time, Portuguese and Spanish slave traders had already been selling Africans as laborers in the Americas – Brazil, for instance – for nearly a century.

Archaeologists work in an area of a dig site associated with Angela on the grounds of the Colonial National Historical Park, in Jamestown, Virginia, U.S., August 19, 2019. /AFP Photo

Nearly a third of the 350 slaves died before the Atlantic crossing was complete because of the dire conditions on board the vessel. And before reaching Veracruz, the remaining slaves were stolen in the Gulf of Mexico by two English privateers. The English ships, the "White Lion" and the "Treasurer," brought them to Virginia where 20 to 30 were "bought for victuals."

In 1625, one of the first Africans, a woman named "Angelo" (Angela), was listed in a colony-wide census as living in the household of Captain William Pierce of New Towne, a well-connected and wealthy planter-merchant, the Foundation states on its website. Some historians disagree on her actual name, which was probably given by the Portuguese.

"To me, the story of Angela is sort of like Eve," Bly Straube, the curator at the Jamestown Settlement, told AFP. "She and her fellow Africans who arrived in 1619 are the founding generation of what would become our African American community today. That's the beginning."

Archaeologist Charde Reid calls the first slaves to reach Virginia as "our foremothers and our forefathers, of not only African American culture, but American culture in general."

The uprising of the enslaved

Their arrival in 1619, in hindsight, is seen as the genesis of a dark period in American history involving 250 years of slave practice subsequently making way for decades of racial discrimination, traces of which are still visible in the American society.

Nearly 171 years after the first slaves arrived in America, a historic event in one of the French colonies in the Caribbean, in what is today Haiti and the Dominican Republic, would set the grounds for the abolition of slave trade.

The night of August 22-23, 1791 witnessed an uprising of slaves in the western part of the island of Saint-Domingue that is considered a turning point in the history of the slave trade. The revolution soon spread from the island to other French Caribbean colonies. The ensuing war continued for 13 years and culminated in 1804 with the independence of that part of the island, which took the name of Haiti, and led to the recognition of the equal rights of all its inhabitants.

It is against this background that the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition is commemorated on August 23 each year.

Superintendent of Fort Monroe National Monument, Terry E. Brown, poses near a historical marker at the fort, in Hampton, Virginia, U.S., August 19, 2019, /AFP Photo

"This 23 August, we honor the memory of the men and women who, in Saint-Domingue in 1791, revolted and paved the way for the end of slavery and dehumanization. We honor their memory and that of all the other victims of slavery, for whom they stand," UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay said in a message for the Remembrance Day.

"The fight against trafficking and slavery is universal and ongoing. It is the reason for which UNESCO led the efforts to launch the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition. This special day acknowledges the pivotal struggle of those who, subjected to the denial of their very humanity, triumphed over the slave system and affirmed the universal nature of the principles of human dignity, freedom, and equality," Azoulay remarked.

Reminding the international community of the "horror of slavery," she described it as "the product of a racist worldview which perverts all aspects of human activity." Azoulay noted that slavery persists even today "in speeches and acts of violence which are anything but isolated and which are directly linked to this intellectual and political history."

The UNESCO director-general insisted that the year 2019 is a particularly important one for this commemorative day. “It is a time for taking stock and adopting new perspectives. It is the midpoint of the International Decade for People of African Descent (2015-2024), proclaimed by the General Assembly of the United Nations to encourage member states to pursue strategies for fighting racism and discrimination.”

In addition, the year also marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of UNESCO's Slave Route Project: Resistance, Liberty, Heritage. "The spotlight will be shone on this anniversary in Benin, where the project was launched in 1994, and where the International Scientific Committee for the Slave Route Project will be invited to look back on the work done and offer new insight into our current global circumstances," Azoulay stated.

The UNESCO chief also took note of Ghana's "Year of Return" and the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first African slaves in Jamestown. "All these commemorations encourage us to continue striving to put a definitive end to human exploitation and to ensure that the memory of the victims and freedom fighters remains a source of inspiration for future generations."

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, between 10 and 12 million enslaved Africans were shipped across the Atlantic to the New World from the 16th to the 19th century, of whom about 2.4 million died during the journey. Thousands more died resisting capture while many more starved themselves to death rather than face humiliation.

Terry Brown, the first black superintendent of the Fort Monroe National Monument, considers the history of slavery in the U.S. as "the greatest survival story written in American history."

Brown and his team have planned a series of events between August 23 and August 25 to celebrate the "contributions" of Africans to U.S. society. "The more we gather around, the more we talk, the easier it is to break with the insidiousness of racism," Brown told AFP.

(With input from AFP)

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3