Editor's note: Tom Fowdy is a British political and international relations analyst and a graduate of Durham and Oxford universities. He writes on topics pertaining to China, the DPRK, Britain, and the U.S. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

On September 6, former president of Zimbabwe Robert Mugabe passed away at the age of 95. Mugabe had ruled the African nation from 1980 to 2017, eventually being removed from power by a military coup.

His passing was met with a mixed reaction from around the world. He was deeply criticized by Western commentators, who saw his legacy as one of misrule and desolation, but nevertheless praised by many others including in Africa itself, for his early role as an anti-colonial revolutionary fighter and activist fighting for the equal standing of African locals against the Rhodesian regime.

Nevertheless, although originating with the right intentions, Mugabe's rule would go on to make many mistakes and decisions which cannot be overlooked easily, including catastrophic economic mismanagement which would severely deplete living conditions and create rampant problems such as corruption.

Still, for Zimbabweans and many throughout the continent, his legacy is likely to be revered than condemned; thus leaving him likely to be remembered globally in a static, binary way.

In Mugabe's youth, what would become "Zimbabwe" was instead known as the British Colony of Rhodesia, a jewel of the Empire whereby a minority of white settlers had enriched themselves at the expense of the majority, African population.

Although not as brutal as its neighbor South Africa in the promulgation of an explicit apartheid system, Rhodesia maintained its racial hierarchy by granting excessive rights and privileges to those who held property, in particular the ownership of farming land and, of course, denying them to those who did not.

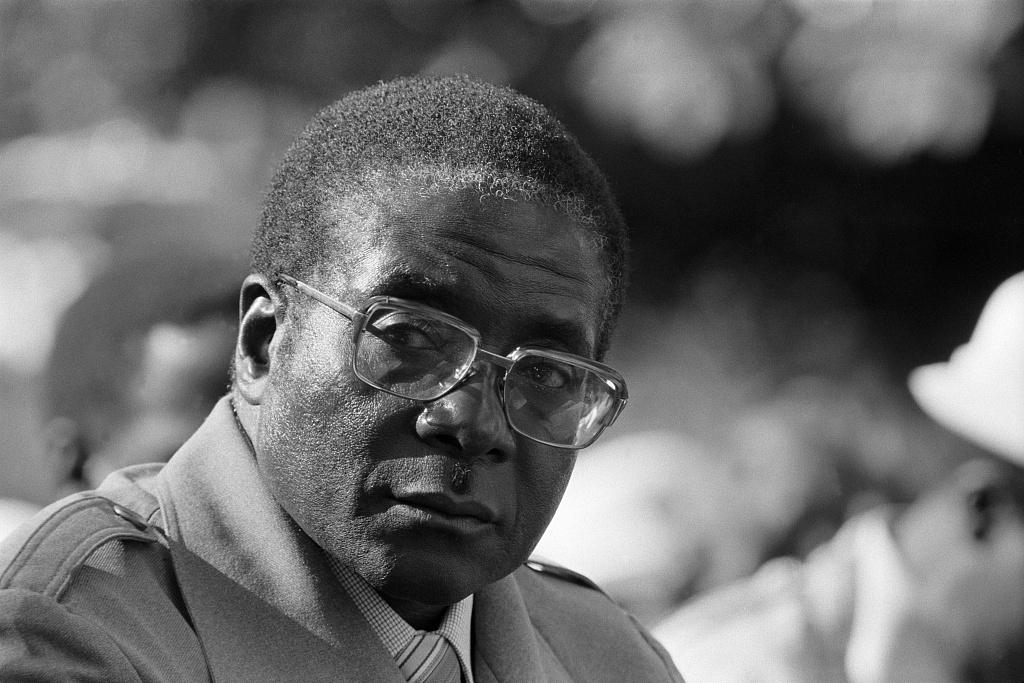

Zimbabwe's then president Robert Mugabe gestures at a "Zimbabwe African National Union" (ZANU) extraordinary congress in Harare, Zimbabwe, December 13, 2007. /VCG Photo

Most significant in this regards was the application of property ownership to the rights of suffrage, thus maintaining the supremacy of white settlers over the country's political system. However in the 1950s and 1960s, this order would become challenged. The British Empire was declining and had committed itself to decolonization whereby its territories were handed over to local rulers.

In tandem with this process, national liberation movements were also sweeping the developing world that sought to achieve the independence and sovereignty of their peoples against their former empires.

Rhodesia became the stage for one of these confrontations. In order to achieve independence, the British government in London requested that the colonial authorities granted the local's majority rule, thus conceding many of the privileges of its white community.

The colony's governor, Ian Smith, was not prepared to agree to this and demanded independence on status quo terms, unilaterally declaring Rhodesia as an independent nation without British recognition.

This, however, would fuel the fires of a liberation movement, inspiring a young teacher known as Robert Mugabe to jump into politics. The future president would serve as a key figure in the Rhodesian Bush War as part of the "Zimbabwe African National Union" (ZANU), and would later end up imprisoned for eight years from 1963 to 1975.

In exile in Mozambique, he was a key figure in ZANU's subsequent guerrilla campaign which would last until Ian Smith giving into international pressure by 1979, paving the way for majority rule in the country.

Mugabe, first as prime minister, would oversee the transformation of Rhodesia into "Rhodesia-Zimbabwe" and then Zimbabwe, pursuing the socialist redistribution of land from white to black families as his core economic policy, of which he encountered difficulties in the willingness of owners to sell, legal challenges, the country's rapidly growing population and the availability of funds to do so.

Zimbabwe's then president Robert Mugabe at a religious service in Paris, April 20, 1980. /VCG Photo

This would impact the country's agricultural and economic development, producing an economic deterioration in the 1980s and 1990s also promulgated by the wider decline in the continent induced by the forced "Opening up" of socialist economies.

Although conditions have since stabilized, the country would suffer from rampant hyperinflation, food insecurity, reducing life expectancies and soaring unemployment. Given this, Mugabe has faced scathing criticism from Western voices, who accuse him of corruption, economic desolation and subverting the country's democracy.

Nevertheless throughout Africa, views of his legacy remained more positive as news of his passing broke. It is important to consider these perspectives above that of Western commentary for the fact that such groups have a habit of pointing fingers and feeling superior to the rest of the world, without quite understanding the full picture and context.

For them, Mugabe is simply a villain, inconceivable to the fact that many Africans saw hope and inspiration in his vision of creating an independent and socialist Zimbabwe.

Of course, given he wasn't perfect and the flaws are too significant to be downplayed, it is likely he will continue to be judged by history in very binary terms, rather than an appeal to nuance in respect of what he sought to achieve, in opposition to the context of which he lived, operated and thus was ultimately shaped by.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com)

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3