Editor's Note: Tom Fowdy is a British political and international relations analyst and a graduate of Durham and Oxford universities. He writes on topics pertaining to China, the DPRK, Britain and the United States. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

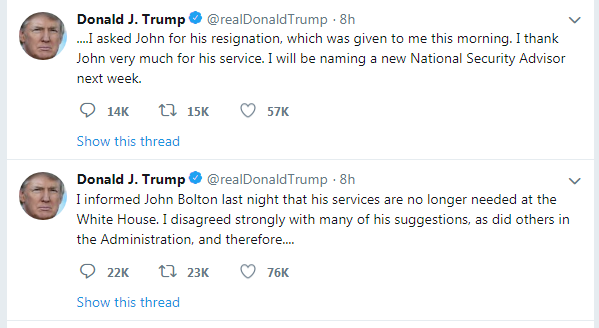

On Tuesday night, U.S. President Donald Trump announced on Twitter that he had informed national security adviser John Bolton that his “services are no longer needed at the White House” and had “asked for his resignation,” citing that he “disagreed strongly with many of his suggestions.” Bolton had joined Trump’s national security team just over a year ago, and owing to his extensive ties within the American bureaucracy and ultra-belligerent, pro-war foreign policy outlook, had gained a reputation among the Washington, D.C. community for steering the President’s decisions toward hawkish causes of action, perceived as a huge detriment on a number of issues.

As a result, it is not surprising to see that his departure is being met with celebration among foreign policy analysts and scholars. Bolton was a notorious and feared neoconservative, but what does his departure signal now for American foreign policy? The former UN ambassador was blamed extensively for a range of Trump policy failures pertaining to Iran, DPRK, Venezuela and Afghanistan. As a result, the president’s bid to jettison his influence may now signal a shift toward reconciliation and diplomacy in these areas, setting the stage for him to “wrap things up” in the view of the 2020 election. However, one should not hold their breath: We don’t know who he will appoint next.

John Bolton was appointed to the position of U.S. national security adviser 18 months ago, following the departure of General H.R McMaster. McMaster had been forced out of the job because of his disagreements with the presidency, being deemed not hawkish enough, particularly on the matter of the DPRK. Bolton was appointed his replacement and came with an established legacy and brand name. He was known and feared in Washington for his relentless pro-war and realist views of foreign policy. Only months before his appointment, he had penned an op-ed setting out why the U.S. ought to bomb the DPRK to resolve the nuclear crisis.

In doing so, he was perceived as a man who did not follow orders but constantly sought to push his own agenda and exert influence over others. He was known for utilizing an extensively entrenched network of ties in the American bureaucracy to get his own way, including the usage of orchestrated tactics such as leaking information and undermining his colleagues, thus steering U.S. foreign policy discourse. In every sense, he was a Machiavellian who knew how to oil the American machine to his own advantage. When appointing him, Trump sought to reassure supporters that he could control him, expressing the usual overconfidence in his own abilities.

However, that turned out not to be the case. Bolton’s role was both dramatic and extremely disruptive to U.S. foreign policy. First, he pushed Washington to the verge of war with Iran by manipulating intelligence reports pertaining to Iran’s nuclear program and subsequently advocating pre-emptive strikes on the country. Secondly, he drove U.S. foreign policy into a botched regime change attempt in Venezuela, also aiming to push it toward military action.

Thirdly, he was infamously blamed for ruining Trump’s summit with DPRK leader Kim Jong Un in Hanoi, having urged the president to reject a deal abruptly in favor of demanding more unilateral terms on denuclearization, something which would receive the vocal condemnation of Pyongyang. After Bolton publicly vowed to place more pressure on the DPRK, Trump began to marginalize him on the issue and even openly disagreed with him. Then finally, he was also perceived to be near the center of blame for the breakdown of talks with the Taliban, something which may have been the tipping point for his departure.

So that begs the question, what now? Bolton was in every instance, opposed to diplomacy and reconciliation and in favor of pressure, belligerence and confrontation. If his successor is in line with following Trump’s own agenda, then the balance of opinion in the White House will tilt more toward rapprochement with other countries. This may open a stumbling block on Trump’s attempt to resolve the aforementioned issues. In the view to his own re-election, the president himself may be aiming now to wrap up deals with Iran and the DPRK and finally put them to bed, something which could have already been long done with the latter.

However, one must not hold their breath. While one of its worst offending members has gone, this is still as a whole a very erratic U.S. administration which even prior to Bolton’s influence held a strong preference for unilateral and coercion-based foreign policy. This is a move in the right direction and one observers can drink to, but we ultimately don’t know who will replace him and where the pendulum will swing thereafter. In any sense, the unpredictability and chaotic character of this White House will continue, albeit in a slightly more tolerable way.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3