The question on the Brexit referendum ballot paper in 2016 was a simple Leave or Remain. The reality of carrying out the Leave instruction has proved to be a little more complicated.

As Britain's bid to leave the European Union heads into its latest crunch point at the end of October, what is expected to happen and what are the biggest uncertainties?

1. What do we know?

What we definitely know is that Prime Minister Boris Johnson has staked his political future on delivering Brexit, "do or die", by October 31, the date by which Britain must currently exit the EU.

We also know that opposition MPs united to pass a law mandating Johnson to request an extension to that deadline on October 19, unless parliament votes for departure via a deal or a no-deal before that date.

We know there is an European Council summit, a meeting of the leaders of all EU member states, is scheduled for October 17-18, which is likely to be decisive if a new agreement is to be hammered out.

We thought we knew that parliament would return from its controversial prorogation on October 14, which would leave just a handful of days for such a vote. However, the government's five-week suspension of parliament has been ruled unlawful in the Scottish courts and the Supreme Court will have the final say on Tuesday – if the verdict goes against Johnson, MPs could be recalled.

2. Is a no-deal still possible?

MPs legislated to prevent an October 31 no-deal by mandating the prime minister to request a Brexit extension on October 19, unless a deal or a no-deal exit had been agreed by parliament.

In Conservative circles the mantra "extension is extinction" is an indication of how bad for Johnson and the party it would be not to keep the promise of a Brexit at the end of October, so strategists and lawyers are desperately searching for legal loopholes.

Possible schemes include provoking the EU into refusing an extension by making the option unpalatable or making a deal with one member of the bloc to block a delay.

Johnson resigning to force another parliamentarian to form a government and make the request is not impossible, but he is unlikely to give up his long-held dream of being prime minister and it would be difficult for any other figure to quickly find a majority in the House of Commons.

Writing one letter calling for more time and another reversing the position has also been floated, but would likely be blocked in the courts. The nuclear option is simply to ignore the new legislation. This would provoke outcry far beyond what has been seen already, with court challenges, mass resignations and even jail sentences possible.

A future no-deal can only be ruled out with a deal or cancelling Brexit, but if Britain does wind up leaving the EU on October 31 without an agreement the next few weeks will be extraordinarily dramatic.

3. Is a deal still possible?

Johnson gave himself little room to maneuver when he said the EU must drop the controversial Irish border backstop and Britain would leave the bloc no matter what on October 31.

The minimal signs of negotiations contributed to over 20 Conservative MPs voting against the government in a bid to block no-deal and subsequently leaving the party. However, MPs' move to prevent a no-deal at the end of October appears to have spurred Johnson into action.

A deal is Johnson's cleanest route out of the corner he's in, and there are now signs that an agreement whereby the backstop covers only Northern Ireland, rather than the entire UK, is in the works.

Johnson will meet European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker on Monday and other European leaders at the UN General Assembly in late September. But even if a deal can be hammered out, it's far from certain a majority of MPs would back it.

4. Will an election be called?

Central to Johnson's grand strategy was to force an election on October 15 that would recreate the playing field of the Brexit referendum.

A united Leave vote for the Conservatives (with Brexit Party voters backing Johnson's absolutist approach) might just win a majority against support for Remain divided between several parties.

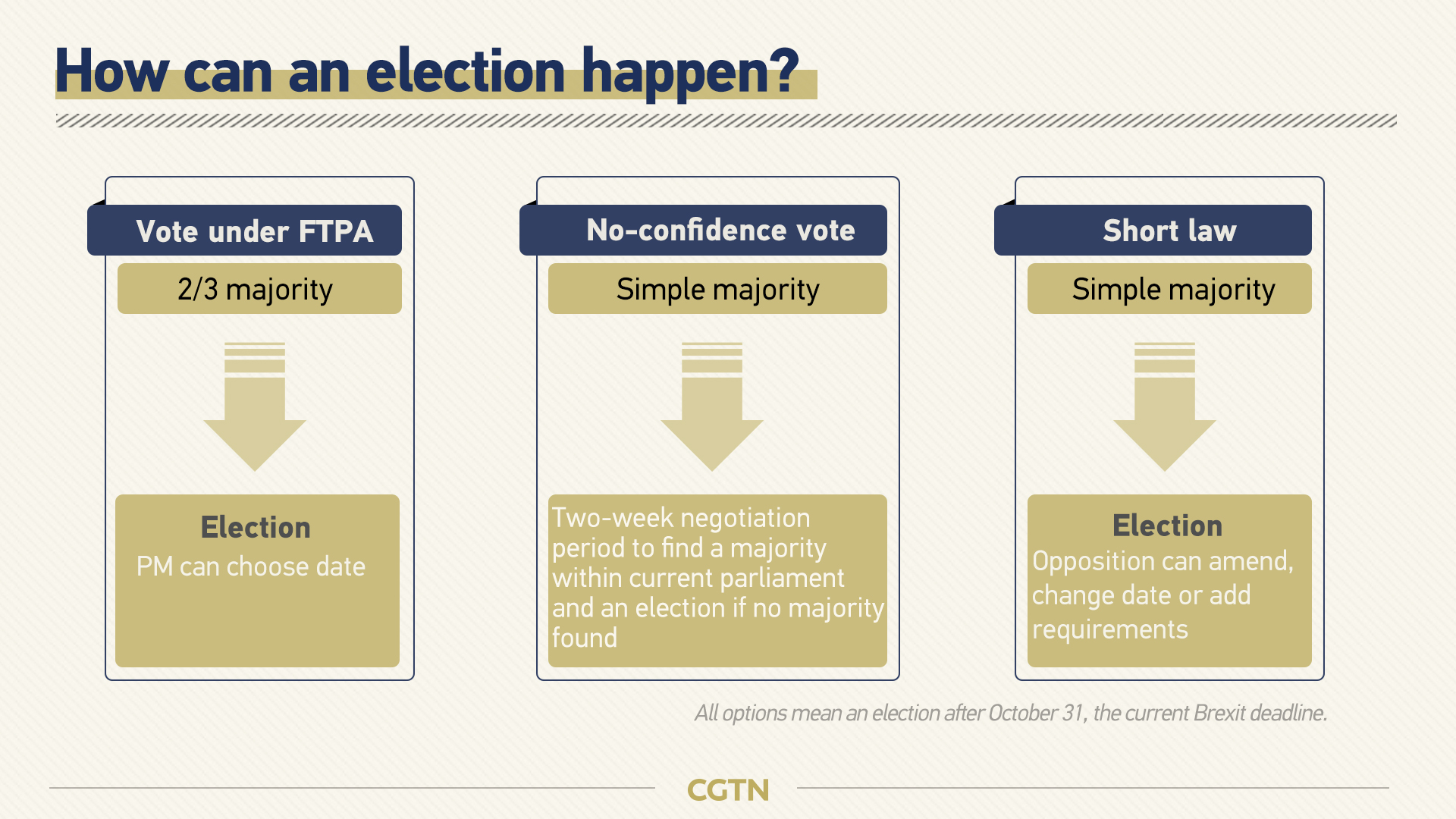

Unfortunately for Johnson, the gambit was undone when the opposition refused to play ball and an election by any of the three possible means before October 31 is now impossible. A later poll is far less palatable for the Conservatives – unless Brexit is delivered.

An election is nevertheless inevitable either way in late November or December. Johnson is governing with a minority of 40-plus, which is unsustainable. And if an extension to the Brexit deadline does take place, the opposition Labour Party would likely call a no-confidence vote in Johnson soon after.

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3

Copyright © 2018 CGTN. Beijing ICP prepared NO.16065310-3