Editor's Note: Guy Burton is a visiting fellow at the Middle East Center at the London School of Economics and an adjunct professor at Vesalius College, Brussels. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Israel goes to the polls on September 17. But it’s not certain who will win. This will be the second election in less than six months; the last one took place in April.

Little separated the two main parties then, and there’s little to suggest that this election will lead to much difference between the two either. What will make the difference is most likely which one will be able to energize their base to come out and vote, given a general apathy among voters.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party and the Blue and White alliance, led by former army head Benny Gantz and former finance minister Yair Lipid, are predicted to have the largest share of the vote, and recent polls point to a difference of one or two seats between them.

Whoever comes first in total seats will have the opportunity to negotiate a coalition, many of them coming from the political right of the spectrum, representing Jewish immigrants, settlers and orthodox Jews.

Benny Gantz, head of Blue and White Party, and his wife Revital, speak to the media before casting their votes on September 17, 2019, in Rosh Haayin, Israel.

Benny Gantz, head of Blue and White Party, and his wife Revital, speak to the media before casting their votes on September 17, 2019, in Rosh Haayin, Israel.

Netanyahu has more of an incentive to form the next government and prolong his status as Israel’s longest-serving prime minister. He is under investigation in three separate cases and so needs to form a majority coalition to gain immunity should the attorney general decide to indict him.

He is accused of accepting bribes in exchange for favors. Perhaps the most egregious is Case 2000 in which he arranged favorable coverage in Israel’s leading newspaper in exchange for legislation to undermine a rival one.

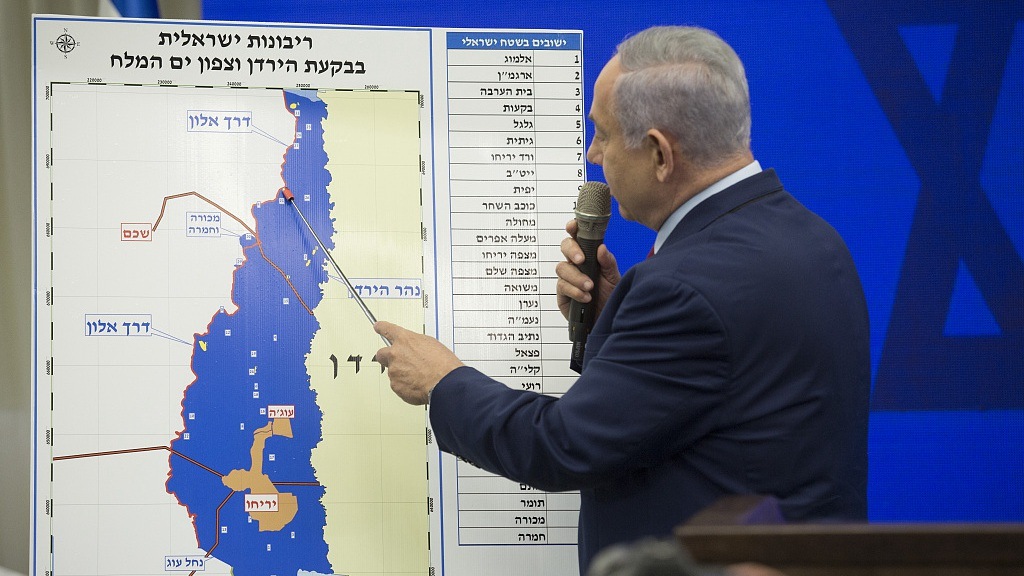

Netanyahu has spent the campaign pressing his own right-wing status. He has promised to annex the Jordan Valley in the West Bank, occupied territory that would be expected to end up in any future Palestinian state should a peace deal be reached.

He has also played on public suspicion and prejudice against the Arab population, which makes up around 20 percent of Israel’s population.

At the 2015 election, he accused them of voting “in droves” while on April he made unsubstantiated claims that Arabs were engaging in voter fraud. Last week, he was condemned for spreading the message that “Arabs want to annihilate us all” on his Facebook page.

Whether Netanyahu forms the next government or not won’t make much difference to Israel’s broad strategy toward the Palestinians and the peace process.

While he has long been against the peace process, Netanyahu has gone slowly on his commitments associated with it since his first premiership in the 1990s and in his current one, which began in 2009.

Meanwhile, the mainstream of Israeli political opinion has moved to the right over the past decade, with the alternative contender for power, the Blue and White alliance, being little more than a mirror of Netanyahu’s Likud. Its leaders, along with those that they and Netanyahu will court after the election, have all served at some time or other in Netanyahu’s cabinet. Should any of them take the top job, it’s extremely unlikely that they will diverge much from the general direction taken to date.

Israeli Prime Minster Benjamin Netanyahu points to a Jordan Valley map during his announcement in Ramat Gan, Israel, September 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

Israeli Prime Minster Benjamin Netanyahu points to a Jordan Valley map during his announcement in Ramat Gan, Israel, September 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

The annexation of parts of the occupied and Palestinian-dominated West Bank has become so mainstream that the main mediator in the currently stalled peace process, the U.S., has not pushed back.

When U.S. President Donald Trump was elected, he made it clear that he would side with Israel. In December 2017, he announced that the American embassy would move to Jerusalem, flouting international convention to wait until the city’s final status had been settled in a peace deal. He also withdrew U.S. funding from the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNWRA), the UN agency responsible for providing services to Palestinian refugees and their descendants, and closed the Palestinians’ representative Palestine Liberation Organization office in Washington.

If Trump thought that these actions would browbeat the Palestinians to accept Israel’s position, it hasn’t worked.

In June, Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, and former property lawyer and Trump’s special envoy to the Middle East, Jason Greenblatt, launched the first part of their so-called “Deal of the Century” to resolve the conflict in Bahrain.

The plan was a glossy brochure of proposed projects and initiatives that would encourage Palestinian entrepreneurship and development, but it struggled to gain traction before its presentation in Bahrain.

The Palestinians rejected it, pointing out that the Oslo peace process in the 1990s had similarly sought to deal with economic matters and leave political issues to the end. Additionally, the Gulf Arab states showed little interest in stumping up the 50 billion U.S. dollars that the plan is expected to cost.

U.S. Vice President Mike Pence shakes hands with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu ahead of his address to the Knesset, Israeli Parliament, in Jerusalem, January 22, 2018. /Reuters Photo

U.S. Vice President Mike Pence shakes hands with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu ahead of his address to the Knesset, Israeli Parliament, in Jerusalem, January 22, 2018. /Reuters Photo

What the Palestinians most care about now is a political solution; from that economic considerations will flow.

But it’s not clear what the U.S. position is on a Palestinian state, now that it seems to be following Israel’s lead and unwillingness to consider anything more than a limited amount of autonomy.

Given this state of affairs, the prospects for the second, political part of the U.S. peace plan are similarly low. Greenblatt’s announcement that he is leaving the special envoy post after the Israeli election will, therefore, make little difference. His replacement is unlikely to either have much time to make changes to the forthcoming plan or impose a new direction on it.

Yet even if Greenblatt’s successor were to offer a new direction, it’s not the lukewarm Arab response they most need to contend with, but the state of public and political opinion in Israel.

That has hardened against the Palestinians over the past few elections and political cycles, and Netanyahu has been both a mover and beneficiary of that process.

Whether he remains in power or Israel finally moves into a post-Netanyahu era, his legacy will be strong.

The simple fact is that Israel is currently in a strong position vis-à-vis the Palestinians and is unwilling to budge.

Moreover, it faces no repercussions for holding that position, by the U.S. or other countries. Until that happens, Israel’s politicians and the public won’t be forced to consider the consequences of their actions and that Palestinian rights and statehood are necessary.

And it’s unlikely that today’s election will do much toward that end.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)