Editor's note: Elizabeth Drew is a Washington-based journalist and the author, most recently, of "Washington Journal: Reporting Watergate and Richard Nixon's Downfall." The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

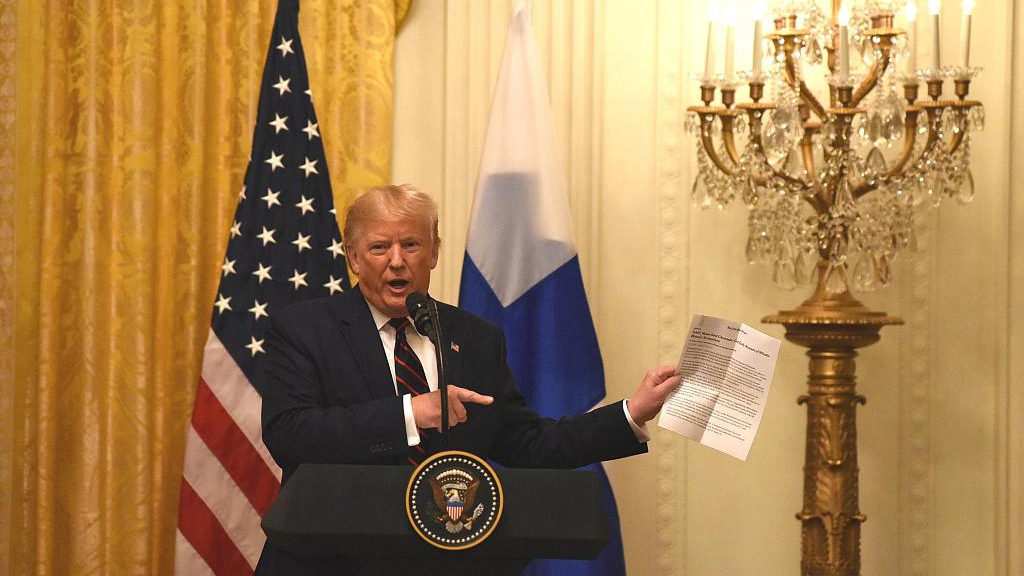

U.S. President Donald Trump's presidency is in peril. He's likely to be impeached (the equivalent of an indictment) by the House of Representatives, and it cannot be ruled out entirely that the Senate will vote to convict him and thus remove him from office. Impeachment alone would leave an asterisk by Trump's name in history. And even if he isn't convicted, which requires a two-thirds vote, any Senate Republican votes against him will undermine his argument that the whole affair is a "hoax."

The issues raised by Trump's recent actions – in particular, his pressuring of a foreign government for his own political benefit (which could be a crime) – are at least as serious as the charges that forced President Richard Nixon to resign in the wake of the Watergate scandal. But until last week, House Democrats, most of whom already believed that Trump should face an impeachment inquiry, had been bumbling along, frustrated by the president's across-the-board efforts to stonewall investigations of his multitude of alleged misdeeds and by Trump-supporting witnesses who got the better of the committees investigating them. Then, out of the blue, came the news that a whistleblower's report regarding Trump was being withheld from Congress, which, by law, was supposed to receive it.

Over a dizzying three days, it emerged that Trump, having held up military assistance to beleaguered Ukraine, which is locked in a war with Russia, had gotten on the phone with that country's young president, Volodymyr Zelensky. Following Zelensky's suggestion that he would like to receive the military funds, Trump replied, in words that have now become infamous: "I would like you to do us a favor, though." Trump went on to press Zelensky to find dirt on former Vice President Joseph Biden, who is now Trump's leading rival for the presidency in 2020. Trump instructed Zelensky to work with his personal lawyer, Rudolph Giuliani, and Attorney General William Barr. But recently the Washington Post cited evidence that the so-called transcript had been edited.

Trump and his allies charge that Biden had pushed for the dismissal of a Ukrainian prosecutor to help his own son, Hunter Biden, who served on the board of a major Ukrainian energy company. That charge has been widely dismissed, not least because the timing simply doesn't work out as Biden's opponents claim. But Trump doesn't exactly cherish the truth, and, despite the trouble Russian assistance in 2016 had caused him, he remains willing to look at "opposition research" from other countries in future elections.

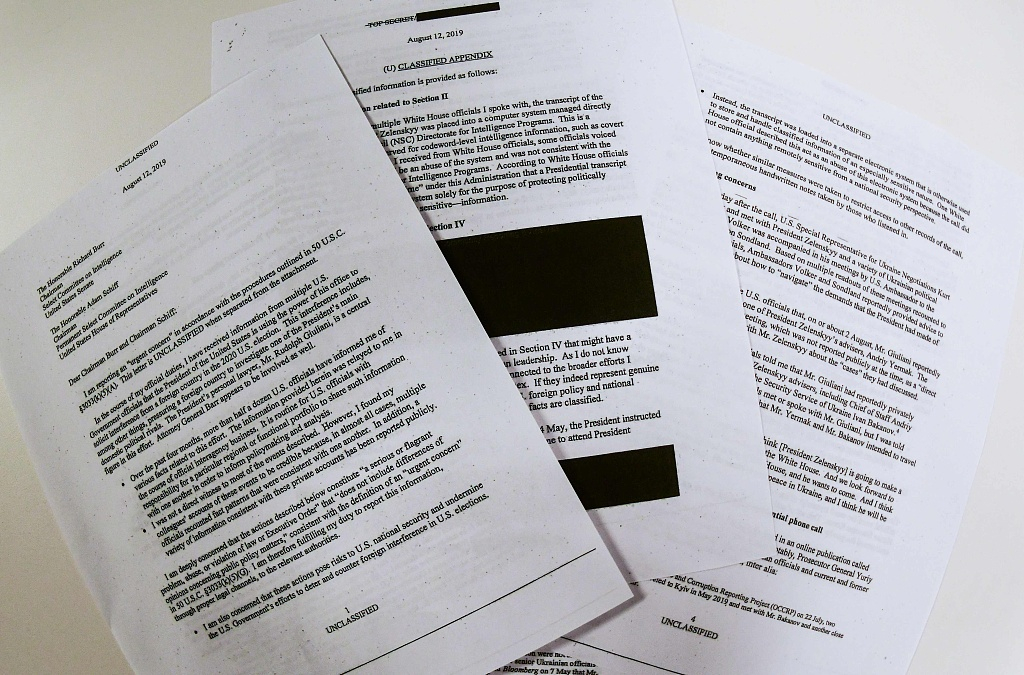

The transcript of Trump's conversation with Zelensky shocked readers in both parties on Capitol Hill. Trump, rejecting his aides' advice, apparently decided to make the transcript public because he thought it was exculpatory. (He must think that everyone talks like a mafia don.) Similarly, the whistleblower's complaint, released under pressure, was chilling and alarming in its details about the extent to which the administration had pressured Ukraine in the interest of the president's personal ambitions.

Photo illustration released on September 26, 2019 shows redacted pages of the whistleblower complaint referring to U.S. President Donald Trump's call with his Ukrainian counterpart Volodymyr Zelensky. /VCG Photo

Photo illustration released on September 26, 2019 shows redacted pages of the whistleblower complaint referring to U.S. President Donald Trump's call with his Ukrainian counterpart Volodymyr Zelensky. /VCG Photo

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, had been resisting calls by Democrats in her caucus to launch impeachment proceedings against Trump. She feared that a highly divisive impeachment process would jeopardize the 41-seat net gain by Democrats in the 2018 election – the party's largest since 1974 (shortly after Nixon's resignation). Although she had numerous allies, their number shrank steadily as evidence of Trump's abuses of power – or even alleged commission of crimes – continued to mount.

Pelosi and her allies also had to confront the possibility that Trump would welcome an impeachment fight. But such a scenario – partly a product of White House propaganda and bravado – is a serious misreading of reality. Trump now seems more unbalanced and mercurial than ever – though he has referred to himself as "a very stable genius". No U.S. president wants to be impeached, because once the process gets underway (as has happened only three times before, against Andrew Johnson, Nixon, and Bill Clinton), there is no knowing how far it might go.

Though much informed opinion holds otherwise, I have never ruled out the possibility that at some point, congressional Republicans, weary of defending Trump's actions, – which they abhor and which may be damaging the party (and thus themselves) – abandon him. That might be beginning to happen. Only a tiny number of congressional Republicans have defended Trump on the merits; instead, others attack the whistleblower or – seriously – Hillary Clinton.

The Ukraine story is now spreading and has pulled in both Barr, who apparently regards the president as a private client, and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, as well as, at the president's insistence, Vice President Mike Pence (a sullied Pence might not seem a viable alternative to Republicans tempted to remove Trump from office). All three men had been trying to distance themselves from Trump's Ukrainian gambit. But Barr has been pursuing fodder for the president's fantasy that Special Counsel Robert Mueller's investigation had suspicious origins, and has traveled to Italy and elsewhere to raise questions (while Trump pressed Australia for assistance). Pompeo, for his part, lied to reporters about his involvement in the effort to pressure Ukraine. While a secretary of state rarely listens in on the president's phone calls with foreign leaders, it turned out that Pompeo was doing so for Trump's call with Zelensky.

As the story spreads, it grows darker. Meanwhile, Trump is trying to learn the identity of the whistleblower (who is protected by law), which could expose that person to great danger. And he is accusing some people – including Adam Schiff, the chair of the House Intelligence Committee – of treason. My sense is that Trump fears the tough, focused Schiff. Trump has ominously noted that traitors used to be shot or hanged. And he hasn't helped himself with members of either party by declaring, in one of his hundreds of febrile tweets, that forcing him from office could lead to a "civil war."

Trump has taken the United States somewhere it's never been before. His presidency may not survive it.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2019.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)