United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres speaks at a news conference at UN headquarters in New York City, September 18, 2019. /VCG Photo

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres speaks at a news conference at UN headquarters in New York City, September 18, 2019. /VCG Photo

United Nations chief Antonio Guterres issued a warning call this week that the organization was running out of money and emergency measures would be needed to pay staff members' salaries come November.

How could one of the world's biggest international agencies, set up to promote peace and security and advance development goals, be low on cash? Here's a look at how the UN's finances work and why purse strings are being tightened.

All 193 member states are meant to contribute annual funds for UN general operations, calculated based on the size of each country and its economy.

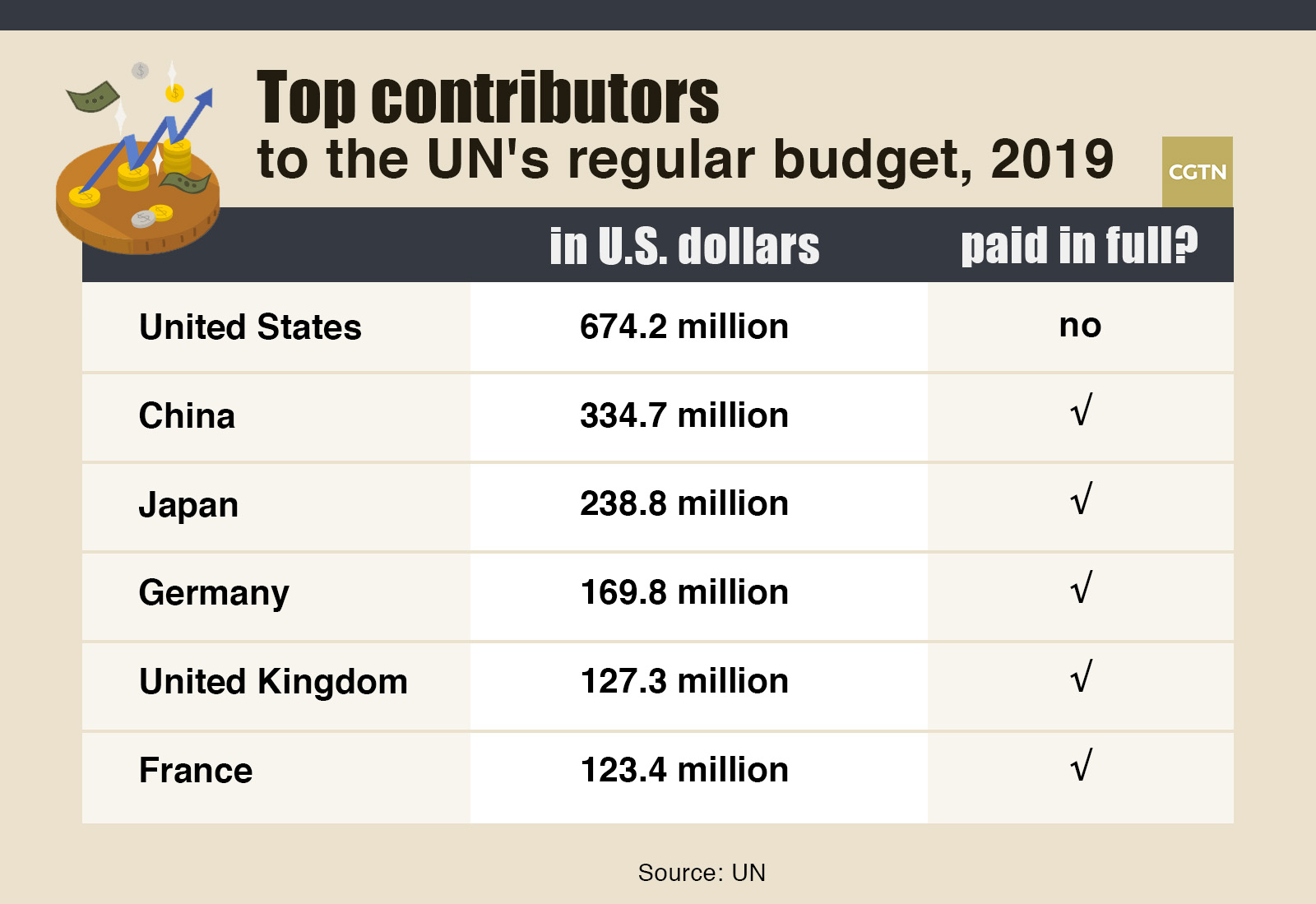

For 2019, net contributions were set at 2.85 billion U.S. dollars, with the U.S. asked to pay the most (about 674.2 million U.S. dollars), and small or poor nations like Vanuatu, Micronesia, Somalia, Belize and Central African Republic paying the minimum of 27,883 U.S. dollars each.

The UN's financial rules and regulations state that this money is "due and payable in full within 30 days" of states being informed of their respective contributions for the year. This year's deadline was January 31.

However, only a few dozen countries ever comply in time. As of October 8, 2019, the UN was still waiting for funds from 63 countries – equaling about 30 percent of contributions.

CGTN Graphic by Li Jingjie

CGTN Graphic by Li Jingjie

Added to this is the fact that many states have a backlog of unpaid annual dues from previous years.

As a result, "we risk ... entering November without enough cash to cover payrolls," Guterres warned this week, urging countries to pay up. With the UN reaching its deepest deficit in a decade, "our work and our reforms are at risk," he added.

The UN's regular budget is used for running operations – including communications and political, humanitarian and economic affairs – at the UN's headquarters in New York as well as its seats in Vienna, Nairobi and Geneva, Switzerland.

Peacekeeping operations and international tribunals – such as the ones for Rwanda or the former Yugoslavia – are covered by separate budgets.

But the current deficit – Guterres called it "the worst cash crisis facing the United Nations in nearly a decade" – has meant drastic measures will need to be taken, including leaving vacant posts unfilled, allowing only essential travel, and cancelling or postponing meetings.

Funds may also need to be borrowed from the money set aside for peacekeeping operations.

The UN employs over 37,500 people worldwide, in its four main centers as well as field offices in Afghanistan, Mali or Haiti. UN agencies like the IAEA, UNICEF or the UNHCR have their own budgets.

U.S. President Donald Trump address the United Nations Security Council in New York City, September 26, 2018. /VCG Photo

U.S. President Donald Trump address the United Nations Security Council in New York City, September 26, 2018. /VCG Photo

Guterres already embarked on some serious cost-cutting earlier this year, or the UN would currently have a deficit of about 600 million U.S. dollars and would have been unable to organize last month's General Assembly – a key annual event attended by leaders from around the world – according to spokesman Stephane Dujarric.

As it is, the UN was running a deficit of 230 million U.S. dollars at the end of September.

Countries like Brazil, South Korea, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Argentina and Venezuela are among those who have fallen behind on their payments.

But among the top six member states – who contribute a third of the UN's general budget – the U.S. is the only one that has yet to pay its 2019 dues in full.

Not only that, it also owes close to 400 million U.S. dollars in arrears, putting its total due payment at over 1.0 billion U.S. dollars, according to various reports.

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres (C) arrives in Beni on the second day of his visit to the Democratic Republic of Congo, September 1, 2019. /VCG Photo

United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres (C) arrives in Beni on the second day of his visit to the Democratic Republic of Congo, September 1, 2019. /VCG Photo

The U.S. has long grumbled about its sizable financial contribution to the UN and President Donald Trump has made no secret about his dislike of multilateralism and his desire to put "America First".

"We reject the ideology of globalism, and we embrace the doctrine of patriotism," he told the UN General Assembly last year. Last month, he told world leaders that "all of our partners are expected to pay their fair share" of defense and other costs.

The Trump administration has already quit the UN's education and culture body UNESCO, citing "mounting arrears" as well as anti-Israel bias in the organisation and a need for fundamental reform.

Washington has also cut support to the UN program for Palestinian refugees UNRWA, complaining of the "very disproportionate share of the burden" it had to shoulder, and to the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) over abortions.

Responding to Guterres comments, Trump tweeted on Wednesday: "So make all Member Countries pay, not just the United States!"