The latest round of Beijing-Washington trade talks ended with a temporary détente on Friday. In the partial trade deal, China agrees to purchase more American farm produce while the U.S. forestalls a tariff hike from 25 percent to 30 percent on a bunch of Chinese goods planned on October 15.

The truce, which U.S. President Donald Trump touted as the "phase one" deal, ran counter to many predictions, but it was hardly surprising. "It reveals that the U.S. needs a partial deal more than China," Zhao Minghao, a long-time China-U.S. observer, told CGTN. He cited the risk of an economic recession in the U.S. as the major motivating factor.

The U.S. Federal Reserve sliced interest rates twice in three months. The move – the first since the 2008 recession – was interpreted as a signal of economic slowdown. In the meantime, the U.S. manufacturing industry is taking its worst hit as the 15-month-long trade war has raised the prices of goods imported from China while thinning out American factory exports.

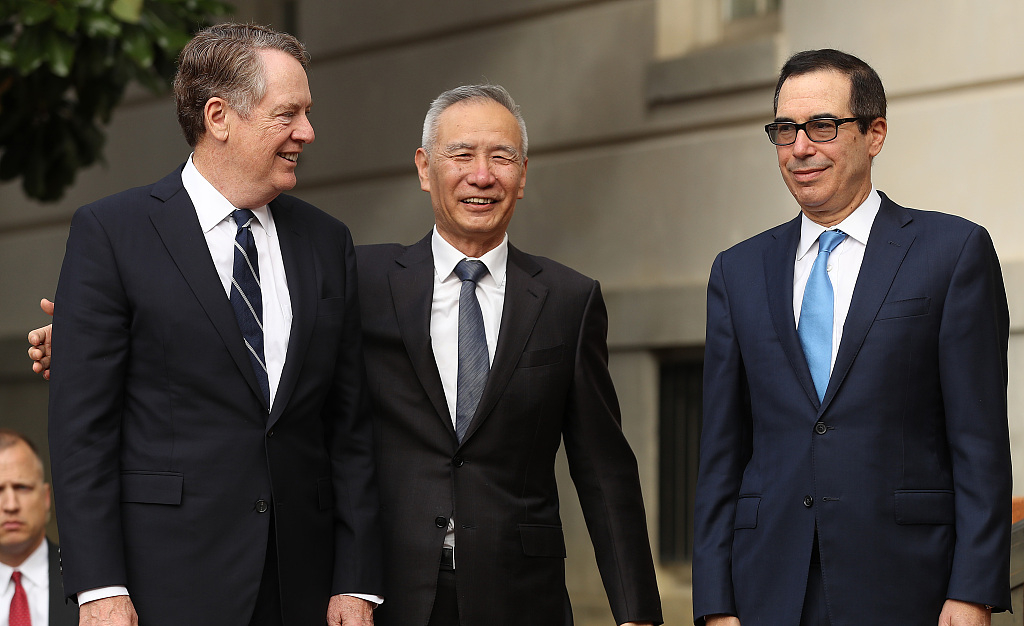

Chinese Vice Premier Liu He (C) poses for photographs with U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer (L) and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin as they begin another round of trade negotiations in Washington, DC, October 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

Chinese Vice Premier Liu He (C) poses for photographs with U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer (L) and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin as they begin another round of trade negotiations in Washington, DC, October 10, 2019. /VCG Photo

The Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) – a leading gauge of U.S. manufacturing activity – tanked to 47.8 percent in September, the lowest since June 2019. And the new export orders index – one of the major survey arenas on which the PMI is based – also slipped to the lowest in a decade, standing at only 41 percent. Other measures, including inventories, raw materials, and backlog, also shrank. The manufacturing contraction starting from August, the first time in three years, has given rise to unemployment. Some 2,000 people working in this sector were laid off in September alone.

Trump has long been drumming up manufacturing revival as one of his "fair" reasons to start the trade war, in a bid to change the status quo of industrial hollowing out and bring back jobs that drained to labor-intensive, developing countries. Nonetheless, things went somewhat awry. It appears that the tariffs did little to help the "forgotten men and women" of the Rust Belt.

People walk by the New York Stock Exchange in New York City, October 1, 2019. The Dow fell over 300 points on Tuesday. /VCG Photo

People walk by the New York Stock Exchange in New York City, October 1, 2019. The Dow fell over 300 points on Tuesday. /VCG Photo

Another indicator of a possible economic recession is eroding profit margins, which has been on a slow, mild decline over the past few years. In the past, lower corporate profits across the board generally preceded a recession.

"President Trump credits himself for the country's economic recovery, including a low level of unemployment and steady GDP growth," said Wang Yong, director of the Center for International Political Economy at Peking University, during an interview with CGTN. "Domestic economy is the most important factor in the reelection, so for Trump now, 'America first' has turned to 'reelection first.'"

Apart from the desire to preserve a buoyant economy, the Trump administration is also trying to divert his voters' attention from the impeachment inquiry.

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks to the media as he departs the White House, headed to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to visit with wounded military members, in Washington, DC, October 4, 2019. /VCG Photo

U.S. President Donald Trump speaks to the media as he departs the White House, headed to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to visit with wounded military members, in Washington, DC, October 4, 2019. /VCG Photo

Trump and his cabinet aren't trying to only get China to buy more agricultural products, said Zhao. It's true that a big spending of up to 50 billion U.S. dollars on soybeans, pork, wheat among other farm produce will bring relief to struggling farmers, many of whom prefer free trade to government emergency aid packages. But that's far from their purpose of the trade accord.

The U.S. has long been voicing a multitude of grievances that it wants China to address, including structural reforms, further opening up of financial markets, and greater enforcement of intellectual property rules. "It's fair to say that the 'phase one' deal made a positive mark, but many tough issues remain to be solved," said Sun Chenghao, an American studies expert at China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations.

Despite the headway Beijing and Washington made, timelines and details of the partial trade deal remain murky. As long as the conflict persists with both sides fundamentally at odds with each other beyond economic interests, the fate of workers and businesses remains uncertain.

After all, it's not the first time the two sides agree to a truce. Argentina and Osaka both witnessed sanguine outcomes, which, however, turned out to be only twists in the bilateral entanglement that are unlikely to lead to a comeback to engagement.

According to U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, the announcement does not have any bearing on a separate tariff set to be imposed on 160 billion U.S. dollars' worth of Chinese goods starting December 15.