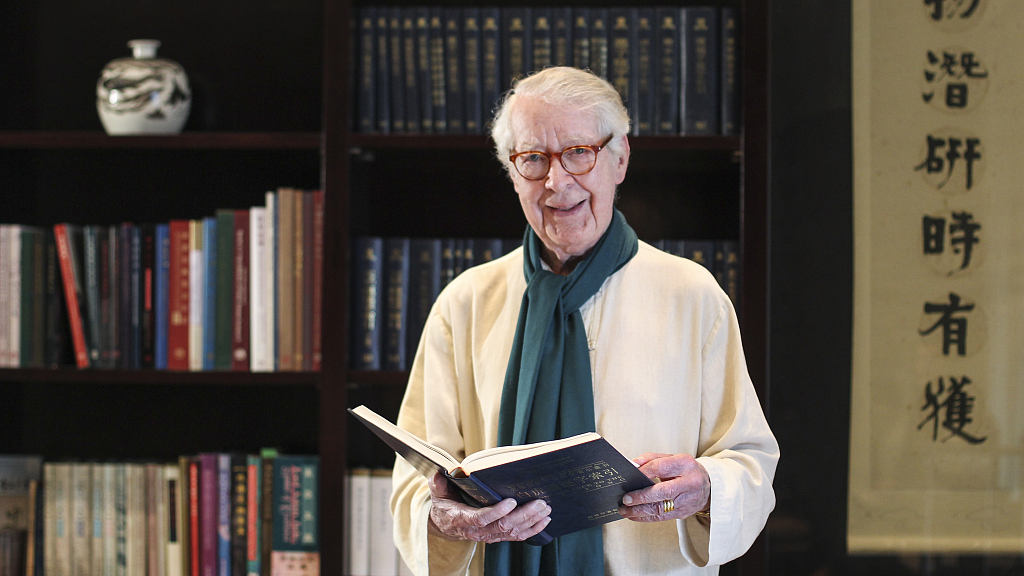

Portrait of Goran Malmqvist. /VCG Photo

Portrait of Goran Malmqvist. /VCG Photo

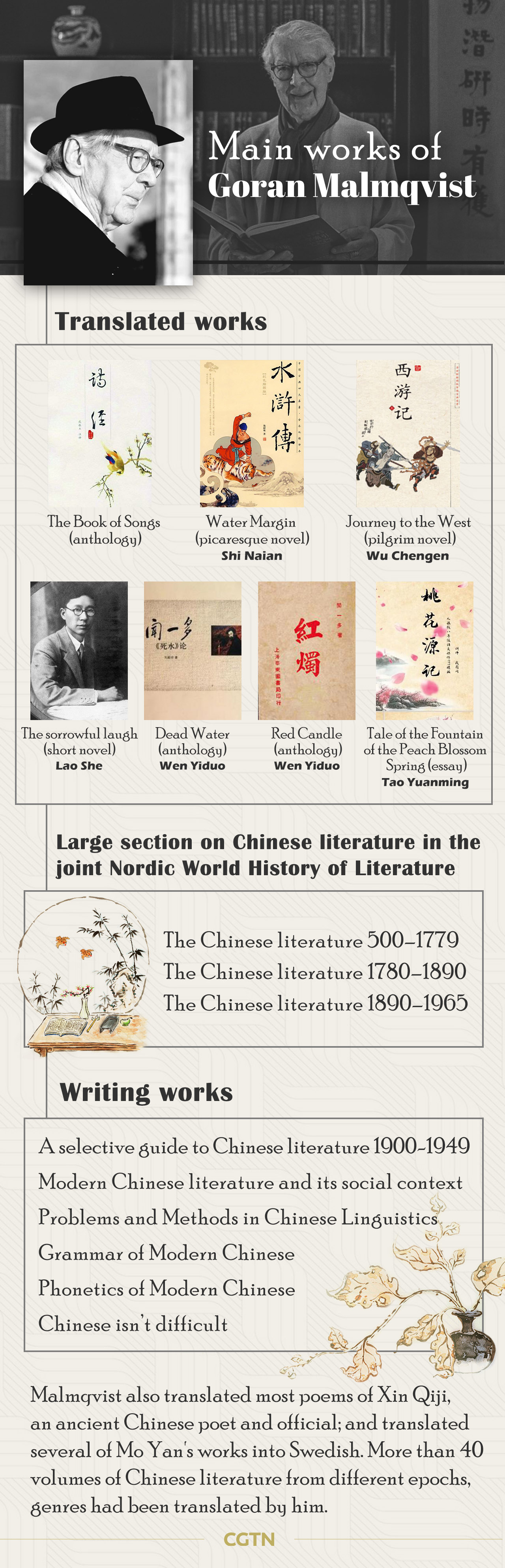

Goran Malmqvist, a famous sinologist and a senior member of the selection panel of the Nobel Prize for literature, passed away in Sweden on October 17, aged 95. Chinese embassy in Sweden expressed deep condolences on its website to the sinologist who translated more than 40 volumes of Chinese literature from different epochs, including widely known Chinese novels: Water Margin, Journey to the West, and the anthology The Book of Songs. He also helped promote Mo Yan who received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2012.

Malmqvist: a champion of Chinese literature

Malmqvist's lifelong love of Chinese culture began in 1946, in which he studied Chinese language and literature in Stockholm University under renowned sinologist Bernhard Karlgren at the age of 22. He had a great talent in Chinese, being able to read classical Chinese literature like The Spring and Autumn Annals, Chuang-tzu and The Book of Songs after only two years of learning, and got a chance to study dialect in China.

The time when he first came to China in 1948, the country was experiencing a revolutionary shift and a series of social changes followed by the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949. And Malmqvist got a more intuitive understanding of these changes during these two years of living in China. He came back to Stockholm to finish his study and once again came back to China in 1956, serving as cultural commissioner of the Swedish embassy in China.

02:57

He successively worked as a Chinese language professor at the University of London, Australian National University in Canberra, and Stockholm University after he left China. During his time in Australia, he published a series of papers relating to Chinese dialects and grammars, and finally created his own research field in Stockholm University: Studying current Chinese literature and culture.

From that year on, his career as a translator also began. He translated more than 40 volumes of Chinese literature and wrote books to introduce Chinese literature classics to Sweden and the rest of the world.

"I'm not a Chinese, but I love to translate these works into my language. I hope the people in my country can appreciate the literature works I like. I want to translate all of the excellent Chinese literature into Swedish, but of course I can't," Malmqvist once said.

As a sinologist, he not only translated several long Chinese classical novels and many important Chinese literature works, but also wrote textbooks to introduce Chinese grammar and culture, including Problems and Methods in Chinese Linguistics, Grammar of Modern Chinese, Phonetics of Modern Chinese and so on. He was praised by Chinese people as "the bridge of Chinese literature to the world."

A love story: Malmqvist and his wife Chen Zuning

Golden ginkgo leaves decorate Huaxiba, Chengdu Province. /VCG Photo

Golden ginkgo leaves decorate Huaxiba, Chengdu Province. /VCG Photo

The remains of historical buildings of Huaxiba, Chengdu Province. /VCG Photo

The remains of historical buildings of Huaxiba, Chengdu Province. /VCG Photo

Golden ginkgo leaves decorate Huaxiba, Chengdu Province. /VCG Photo

Golden ginkgo leaves decorate Huaxiba, Chengdu Province. /VCG Photo

The remains of historical buildings of Huaxiba, Chengdu Province. /VCG Photo

The remains of historical buildings of Huaxiba, Chengdu Province. /VCG Photo

Malmqvist's understanding of Chinese not only originated from his academic background, but also from his married life. He married twice in his life and both his wives were Chinese. He spent 46 years with his first wife, Chen Ningzu.

The couple met in the autumn of 1949, when Malmqvist was researching dialect of southwest China in Chengdu City. He stayed in Chen's home located in Huaxiba – the place is to Chengdu what Oxford and Cambridge are to London. Chen's father was a local well-known educator and acquaintance of Malmqvist's mentor in China. He invited Malmqvist to teach his daughter English, but the little daughter was not interested.

"Zuning is reluctant to learn English, but she couldn't go against her mother. Her mother asked her to learn English from me for an hour every day. I bought several tins of cocoa powder in a shop and made cocoa tea for her. But she dropped classes every time when she drunk off the tea," Malmqvist recalled.

During the days when he was in Chengdu, Chen accompanied Malmqvist to buy old books, and Malmqvist invited Chen to watch movies. He stayed there for seven months, and on the last day he left for Hong Kong, Chen's family held a farewell party for him, on which Chen played piano and sang Chinese folk song, Somewhere Far Away, for him. He left, but his heart stayed with the song, as well as the beautiful Chengdu girl.

When the man arrived in Hong Kong, he proposed to Chen via telegraph and 20 days later, the couple met in Hong Kong, and got married soon after. Chen spent her entire life with Malmqvist until her final day in Stockholm in 1996.

World literature is translation

His married life and his academic background enabled him to understand Chinese and China much better. And he was anxious to introduce Chinese literature to the world, allowing more people to know and appreciate it.

In 1985, he was elected as a member of the Swedish Academy and became the only one of the Nobel Prize committee who was proficient in Chinese. Since then, he has spared no effort to promote Chinese literature and writers, especially Shen Congwen, who was slated to win the 1988 Nobel Prize for Literature, but died before he could be awarded. Nobel prizes are not awarded to people who have passed away.

"Among so many Chinese writers, Shen Congwen is the most person who is eligible to win the Nobel Prize. If he could have died a few years later, he must be the first one to win the prize," Malmqvist said, "Shen doesn't have the aloof and proud of many litterateurs. He is a bumpkin, and he knows the sufferings and hardship of the lower class, so he could write great novels like Border Town and Long River."

Shen's missed-out on the Nobel Prize not only because of his death, but because of a delayed better translation of his work. Americans translated his work very early, but didn't translate it fully and fairly. Only after Malmqvist translated a lot of works of Shen into Swedish, did his work gain attention and popularity among Malmqvist's colleagues.

He also noted that China has a large amount of excellent novelists and poets in the past century, and many of them were qualified to receive the Nobel Prize. But more or less because of poor translation, their works were not accepted by the West.

"What makes me angry, really angry, is when an excellent piece of Chinese literature is badly translated. It's better not to translate it than have it badly translated. That is an unforgivable offence to any author. It should be stopped," he cried when he was interviewed by Xinhua News Agency several years ago.