Britain's Prime Minister Boris Johnson speaking in the House of Commons in London on Oct 29, 2019. /VCG Photo

Britain's Prime Minister Boris Johnson speaking in the House of Commons in London on Oct 29, 2019. /VCG Photo

Editor's note: Richard Fairchild is an associate professor at the Finance of School of Management at the University of Bath. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily those of CGTN.

It has been a momentous few days in the Brexit saga. On October 28, the EU agreed to Britain's request for a Brexit "flextension" to January 31, 2020.

What is "Flextension?" It means a flexible extension: There are "break-points." Britain could leave on November 31 or December 31, 2019 if, by some miracle, a deal agreed by the EU and UK Parliament by those dates. So effectively, the "flextension" has taken no-deal off of the table, at least until January 31, 2020.

The outgoing EU President Donald Tusk has warned Britain not to waste the extra time given: Work to get a deal done. And he cautioned that this might be the last extension that the EU grants to Britain. He has said all of this before: For example, after the extension was granted from March 31 to October 31 2019.

Following the "flextension," British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has finally been able to get Parliament to agree to holding a general election before Christmas, on December 12, 2019. MPs overwhelmingly voted for this yesterday (Oct. 29), with 438 MPs voting for the general election, and only 20 voting against it.

What does this election mean for Brexit? Although the parties will be campaigning on many issues (for example, Johnson's Conservatives will promise extra investment into the National Health Service and the Police, while Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party will campaign for increased investment into Public Services, and for workers' rights), it is seen the vote will likely reflect the public's Brexit preferences.

The Conservatives are standing as the party for Brexit (as Johnson says, "vote for us, and let's get Brexit done"). Labour is pushing for a fresh referendum on Brexit. The Lib-Dems and the Scottish National Party (SNP) are explicitly supporting a campaign for Remain.

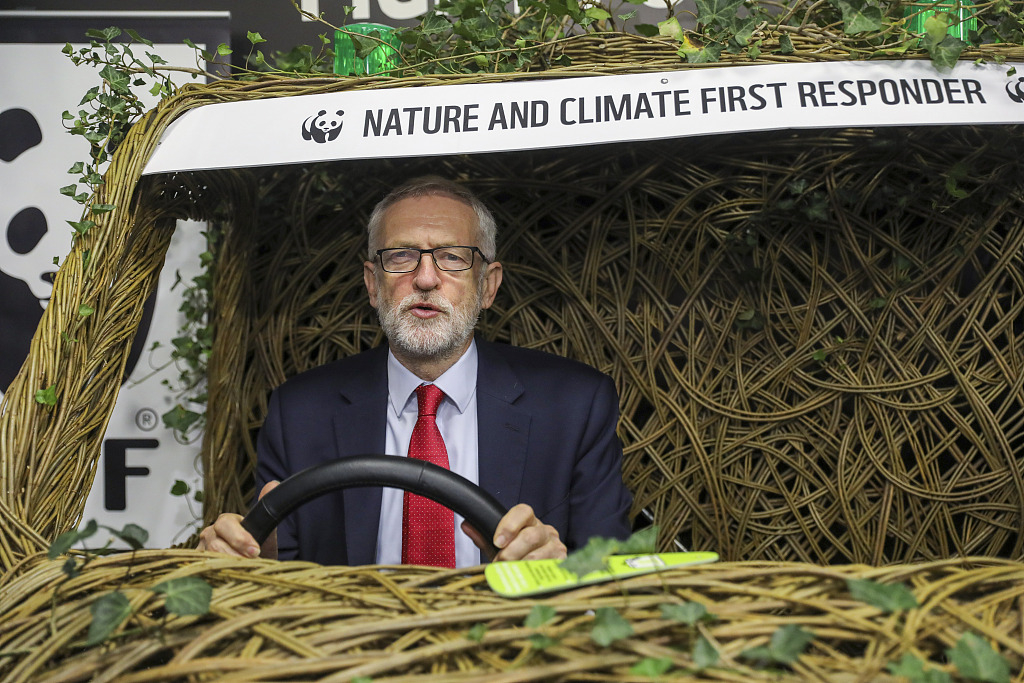

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party, sits in car at the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) stand, Brighton, U.K., Sept. 23, 2019. /VCG Photo

Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party, sits in car at the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) stand, Brighton, U.K., Sept. 23, 2019. /VCG Photo

Given the knife-edge result in the 2016 referendum (52 percent voted for Brexit, and 48 percent voted against), the opinion polls are now showing a similar close call of views among the British public. The outcome of the general election appears to hang in the balance.

If the public votes according to these Brexit preferences, we could probably be in for another hung parliament, with no clear majority for either party. This has been a major problem for Brexit negotiations since the 2017 General Election resulted in a hung parliament. Johnson's predecessor Theresa May had to do a deal with the Irish DUP (Democratic Unionist Party), among which there were 20 MPs who enabled her to gain a majority. So everything she tried to do around Brexit had to be agreed with the DUP.

If there is a hung parliament again in the December 2019 General Election, it will be back to square one in trying to secure Brexit by January 31 2020: The same deadlock and paralysis at Westminster.

On the other hand, could there be a huge swing to either of the two major parties (Conservative or Labour), so they can then be decisive in their policy-making. But is that possible?

Traffic passes through Streatham High Road in south London, Britain, Sept 11, 2019. /VCG Photo

Traffic passes through Streatham High Road in south London, Britain, Sept 11, 2019. /VCG Photo

An interesting proposition around the vote was put forward by the BBC's political editor Norman Smith in an interview on BBC News on October 29 ("EU agrees Brexit Extension to 31 January". BBC News October 29 2019). He argued that the general election is a huge risk for Johnson. How will the British public vote, given that Johnson had promised Brexit by October 31 2019, and would rather be "dead in a ditch" than not leave that day (just as May had promised Brexit by March 31st 2019)?

Smith argues that this could work in one of two possible ways at the polls. The public may view Johnson as somebody who pulled out all of the stops to try to get Brexit done by the end of October 2019, but was thwarted and frustrated by Parliament. This may strengthen public sentiment towards him at the election. However, on the other hand, the public may see him as someone who makes false promises that he does not deliver on, and may turn against him.

It is interesting that Smith said that "the public may punish him for not delivering the Brexit that he promised." If so, the punishment will probably be the voters' voting against Brexit and delivering a party (Labour) who wants a fresh referendum, or Lib-Dems (who want to force Remain).

This would be a real contradictory situation, supported by psychology research that has shown that people who are angry can engage in retaliation, even if it costs themselves in terms of their own goals and desires. The anger and emotion of those who are upset that Brexit did not happen on October 31 2019 could lead them to retaliate by voting against Johnson, thus destroying Brexit.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)