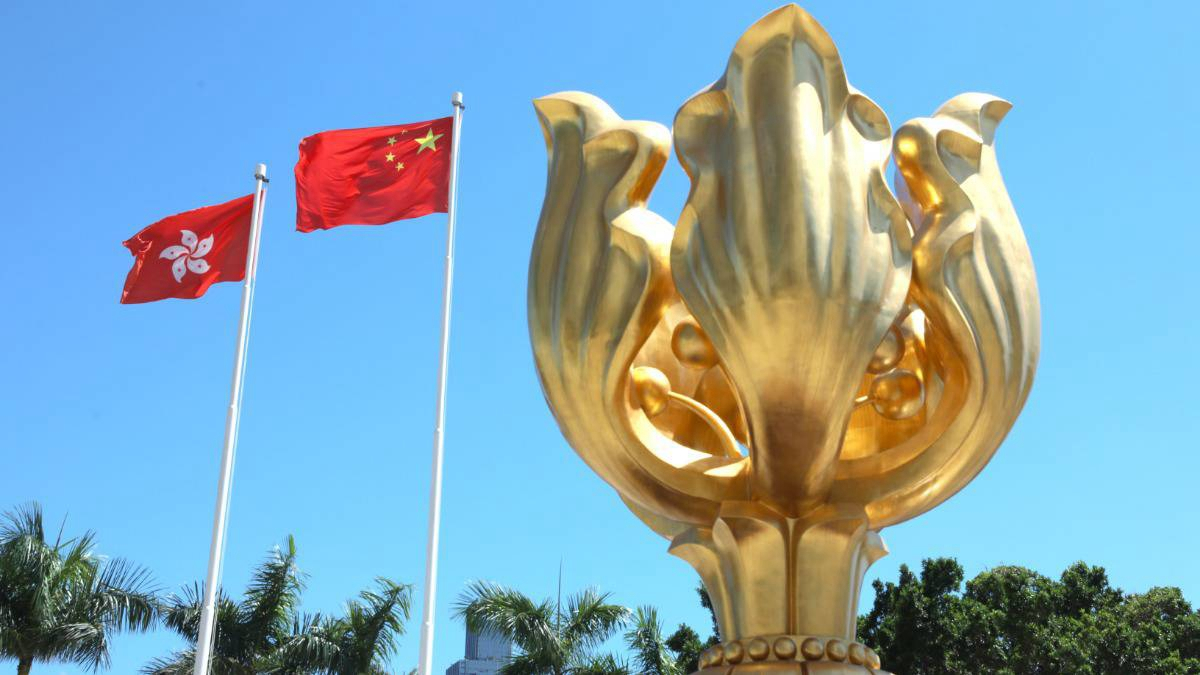

The Chinese national flag and the flag of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region fly above the Golden Bauhinia Square in Hong Kong, China, August 5, 2019. /Xinhua Photo

The Chinese national flag and the flag of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region fly above the Golden Bauhinia Square in Hong Kong, China, August 5, 2019. /Xinhua Photo

Editor's note: Zhu Zheng is an assistant professor focusing on constitutional law and politics at China University of Political Science and Law. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The Chinese government in 2014 designated December 4 as National Constitution Day, encouraging all Chinese to observe this important document by attending various lectures and events, and hopefully lifting people's comprehension of it to a new height in the process.

As the unrest continues in Hong Kong, it might be a proper occasion to discuss the safeguarding of "One Country, Two Systems" and the Basic Law. The overarching formula of "One Country, Two Systems" under the Basic Law endows Hong Kong with a special status and imposes restrictions at the same time.

After Hong Kong returned to China in 1997, the Basic Law promised that Hong Kong could continue to enjoy a high degree of autonomy, its capitalist way of life unchanged and political, legal and financial systems would be retained. However, the Basic Law openly declared that the autonomy of Hong Kong is subject to some limits.

In his famous speech in 1983, Deng Xiaoping said: "There must be limits to autonomy, and where there are limits, nothing can be complete. Provided the national interests are not impaired, it will enjoy certain powers of its own that the others do not possess."

In his elaborations, Deng expressed the view that it is to the benefit of Hong Kong for the Central Authorities to retain some power there: "There will always be things you would find hard to settle without the help of the Central Government."

One of the powers retained by the Central Government is the final say on controversial issues. After all, the Basic Law as a deeply complex and even "flawed" instrument allows many articles to be construed in different ways.

Delegates attend the Basic Law Seminar in Commemoration of the 20th Anniversary of the Establishment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region in Hong Kong, China, November 16, 2017. /Xinhua Photo

Delegates attend the Basic Law Seminar in Commemoration of the 20th Anniversary of the Establishment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region in Hong Kong, China, November 16, 2017. /Xinhua Photo

For instance, shortly after the resignation of Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa in 2007, it gave rise to the question on the term of the new chief executive, on which Beijing and Hong Kong could not reach an agreement.

According to the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (China's top legislature), "a new Chief Executive" is determined by the method of election, and Donald Tsang, who was elected by the same Election Committee, should not be deemed as "a new Chief Executive," and his term of office accordingly should only be the remaining term of the outgoing chief executive.

Hong Kong people, however, argued that under the Basic Law, the term of office of a new chief executive, regardless of the method of selecting, should be exclusively prescribed and determined by Article 45, which makes it clear that the chief executive is elected with a five-year term of office.

To say the least, if the reading of the Hong Kong court were adopted, i.e. the new chief executive was elected with a five-year term, it would have made the last chief executive's term of office go beyond 2047, which is at odds with the 50-year policy. The judicial review to challenge Beijing was quashed after the Standing Committee made its interpretation.

The above case, along with the cases involving right of abode, shed some light on the inherent differences between Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland over the Basic Law.

The special administrative region tends to read the Basic Law literally, focusing only on articles and words, whereas Beijing keeps a close eye on a broader picture by taking into account the legal, social and political implications.

With an aim to manage risks and maintain the stability and prosperity of Hong Kong, the NPC Standing Committee has a final say over Hong Kong issues.

In a nutshell, the Basic Law as a legal instrument leaves so much space for different readings, it reminds us of the challenges ahead. While the 50-year commitment toward Hong Kong's high autonomy is to be untainted, it is vital to bear in mind that the national interests should put high on the agenda.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)