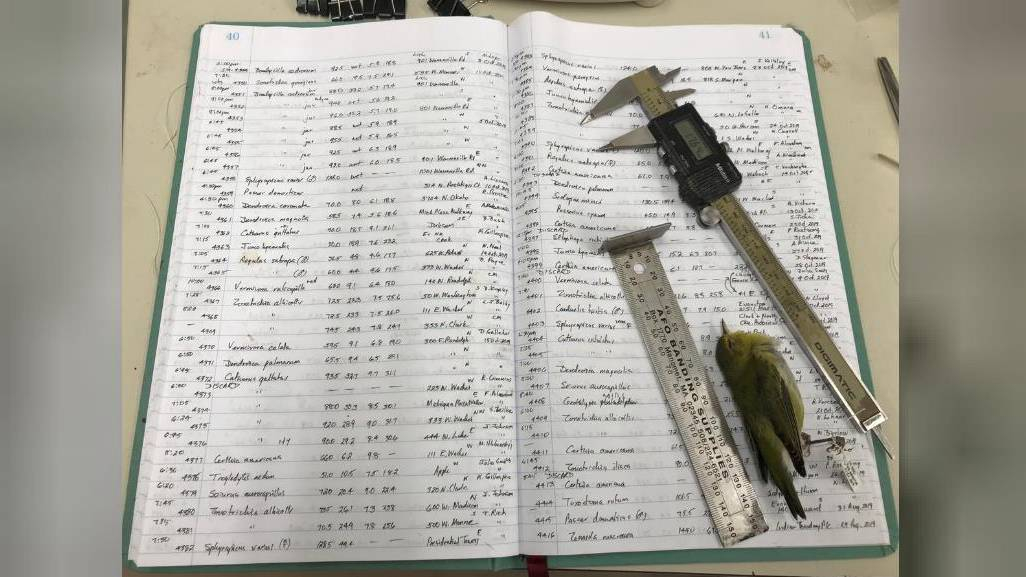

Ledgers recording body size measurements, measuring tools and a Tennessee Warbler belonging to Field Museum scientist, Dave Willard, who took measurements of 70,716 bird specimens of migratory birds that died in collisions with buildings in Chicago over a period of about four decades. /Reuters Photo

Ledgers recording body size measurements, measuring tools and a Tennessee Warbler belonging to Field Museum scientist, Dave Willard, who took measurements of 70,716 bird specimens of migratory birds that died in collisions with buildings in Chicago over a period of about four decades. /Reuters Photo

Since 1978, researchers have scooped up and measured tens of thousands of birds that died after crashing into buildings in Chicago during spring and fall migrations. Their work has documented what might be called the incredible shrinking bird.

A study published on Wednesday involving 70,716 birds killed from 1978 through 2016 in such collisions in the third-largest U.S. city found that their average body sizes steadily declined over that time, though their wingspans increased.

The results suggest that a warming climate is driving down the size of certain bird species in North America and perhaps around the world, the researchers said. They cited a phenomenon called Bergmann's rule, in which individuals within a species tend to be smaller in warmer regions and larger in colder regions, as reason to believe that species may become smaller over time as temperatures rise.

Some of the thousands of birds in the collection of the Field Museum in Chicago that collided with city buildings. /Reuters Photo

Some of the thousands of birds in the collection of the Field Museum in Chicago that collided with city buildings. /Reuters Photo

The study focused on 52 species – mostly songbirds dominated by various sparrows, warblers and thrushes – that breed in cold regions of North America and spend their winters in locations south of Chicago. The researchers measured and weighed a parade of birds that crashed into building windows and went splat onto the ground.

Over the four decades, body size has decreased in all 52 species. The average body mass fell by 2.6 percent. Leg bone length dropped by 2.4 percent. The wingspans increased by 1.3 percent, possibly to enable the species to continue to make long migrations even with smaller bodies.

"In other words, climate change seems to be changing both the size and shape of these species," said biologist Brian Weeks of the University of Michigan's School for Environment and Sustainability, lead author of the study published in the journal Ecology Letters.

"Virtually everyone agrees that the climate is warming, but examples of just how that is affecting the natural world are only now coming to light," added Dave Willard, collections manager emeritus at the Field Museum in Chicago who measured all the birds.

The study provides fresh evidence of worrisome trends for North American birds. A study published in September documented a 29-percent avian population drop in the United States and Canada since 1970 and a net loss of about 2.9 billion birds.

"I think the message to take away is this," Weeks said. "As humans change the world at an unprecedented rate and scale, there are likely widespread and consistent biotic responses to environmental change."

Source(s): Reuters