Years ago, cherries from the state of Washington were among the top-selling U.S. products on China's premium e-commerce site Tmall. This year on the same platform, American cherries are rare. Cherries from Chile, instead, are the most coveted fruits.

Cherries are some of the earliest goods that benefited from the global expansion of e-commerce in China. In 2014, Peter Verbrugge, a third-generation American farmer and president of the fruit production company Sage Fruit, was one of the six bell-ringers when Alibaba went public in the U.S. stock market.

His credentials include holding the record for selling the highest amount of fruits via e-commerce between China and the U.S. In a 2013 pre-sale promotion campaign on Tmall U.S., more than 55,000 people placed their orders for Verbrugge's cherries in just 10 days, totaling 108,000 kilograms, an equivalent of daily sales in 1,000 large supermarkets.

The revolutionary sales model, through bypassing traditional distribution networks, cuts out middlemen and lowers costs, said Tmall.com spokeswoman Florence Shih, according to a report published by Tmall's parent company Alibaba.

A bucket of just picked cherries in Martinsburg, West Virginia. /AP Photo

A bucket of just picked cherries in Martinsburg, West Virginia. /AP Photo

In order to let those highly perishable cherries reach the China market as soon as possible, charter planes were employed so that cherries just taken down from trees in Washington can reach China in 48 hours. The cherries were flown from the West Coast straight to Shanghai, after which they would be immediately packaged and sent to customers across China.

In 2017, the U.S. exported 27,000 tons of cherries to China, a 95-percent increase from the last year, thanks to the burgeoning appetite for the premium fruit among the rising middle class in China.

As the trade war hit, the boom in cherry trade between the U.S. and China turned sour almost overnight. In April last year, a 15-percent retaliatory tariff from China was slapped on cherries from the U.S., in response to the U.S's Section 232 tariffs imposed on Chinese steel and aluminum imports.

A cherry picker works in the cherry orchards. /AP Image

A cherry picker works in the cherry orchards. /AP Image

Two months later, an additional 25-percent tariff was put in place, coupled with a 10-percent tariff increase in September this year. All these effectively bring the total tariff level on cherries up to 60 percent, according to Northwest Horticultural Council, a non-profit trade association that represents the tree fruit industry of the Pacific Northwest in the U.S.

Since China is the top export market for northwest cherry growers in the U.S., the trade war spell doom for the business. The damages are inflicted most heavily on producers in the top five sweet cherry producing states, including Washington, Oregon, California, Michigan and Idaho, which account for 89.7 percent of U.S. cherry exports as of 2018.

According to local newspaper Yakima Herald, the Pacific Northwest states shipped more than three million 20-pound boxes in 2017. After two rounds of tariff hikes, shipments dropped to 1.7 million, a drop of around 40 percent.

Workers pile up boxes of cherries to be processed at a fruit processing company, Shandong Province, China, June 3, 2019. /Getty Image

Workers pile up boxes of cherries to be processed at a fruit processing company, Shandong Province, China, June 3, 2019. /Getty Image

Previously, from May to November, cherries were mostly available from the U.S. and Canada. From November to February, the main supply would switch to cherries from Chile. And now as American cherries lost their competitiveness, cherries from Chile and Canada took major foothold of the void.

"Now cherries from the U.S. are more likely to be taken for examination at the customs, and thus the risks associated with the business is higher," said Fiona Jiang, a representative from Hunan fruit-mate Agricultural Science & Technology Co. Ltd, a company specializing in fruit and vegetable trade. "With less wholesalers and retailers willing to be in the business, the supply of American cherries naturally goes down."

Cherry imports from Turkey, Argentina and Uzbekistan have all gone up, though the number is still insignificant to fill the void left by sweet cherries from the U.S., she added.

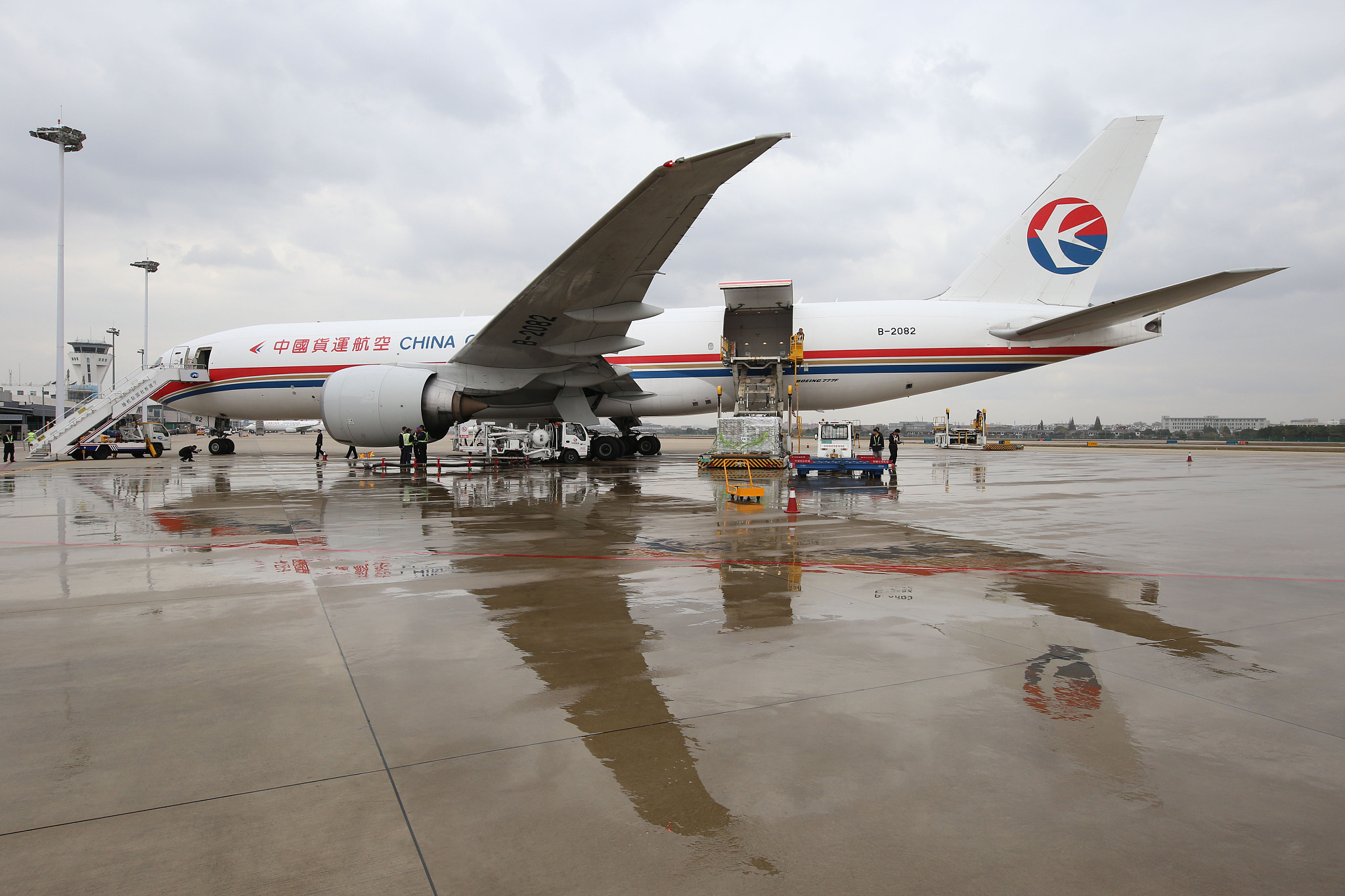

Boeing 777F freighter carrying over 100 tonnes of Chilean cherries lands at Ningbo Lishe International Airport, November 20, 2019. /Getty Images

Boeing 777F freighter carrying over 100 tonnes of Chilean cherries lands at Ningbo Lishe International Airport, November 20, 2019. /Getty Images

A lack of advanced transport infrastructure, and cold-chain networks for preserving cherries at low temperature still plagued the cherry business in Uzbekistan, according to Jiang, resulting in cherries from Uzbekistan not being preserved in their best condition.

On the other hand, cherries from Chile are performing well. China accounted for 88 percent of Chilean cherry exports last year, and this year it is expected that Chile's cherry export to China will grow by 16 percent, according to the Chilean Fruit Export Association.

The increase in trade is a direct result of more convenient air travel between the two. In the past, charter plane carrying cherries all need to go through customs in places like Shanghai and Guangzhou, and now more cities are allowed to directly import cherries from Chile to cut short the transport time.

While Chile is currently reaping the benefit of a free trade agreement with China, American cherry farmers find themselves having to bear the brunt of uncertain weather, on top of turbulent tariffs. Fortunately for consumers, it doesn't matter that the source country of the fruit shifts, as long as the taste stays the same.