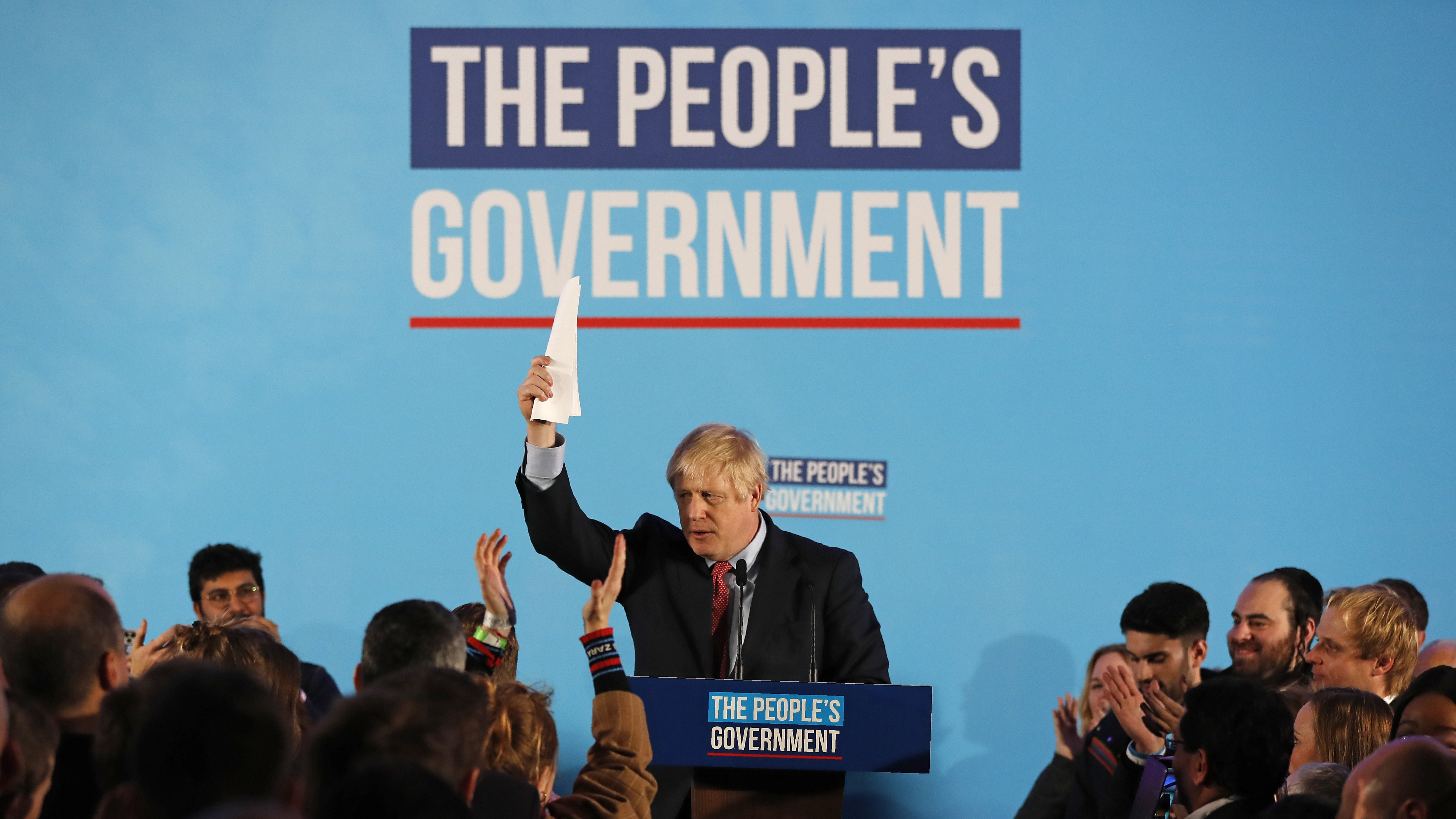

Boris Johnson's new slogan was emblazoned on the wall behind him as he a gave a victory speech. /AP Photo

Boris Johnson's new slogan was emblazoned on the wall behind him as he a gave a victory speech. /AP Photo

Editor's note: Mike Cormack is a writer, editor and reviewer mostly focusing on China, where he lived 2007-2014. He edited Agenda Beijing and is a regular book reviewer for South China Morning Post. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The result of the British general election on Thursday shocked many. The Conservative party under Boris Johnson won a thumping majority of 80 seats, while the opposition Labour party delivered its worst result since 1935. The result is all the more remarkable given how tumultuous British politics have been since the 2016 Brexit referendum, with the country split and unable to come to any resolution on its departure from the EU. But here is a decisive outcome, at last, a conclusive verdict that will enable the Conservatives to govern for five years and to finally, as so often touted during the campaign, "get Brexit done."

The result did not look like it was going to be so clear beforehand. The Conservatives faced an uphill battle in trying to win seats far outside their usual territories, in northern England and working-class areas. Labour meanwhile had done well in the 2017 election and campaigned again on a manifesto promising substantial increases in public spending, after nine years of austerity.

The smaller parties also said ahead of the election that they would not cooperate with the Conservatives, should they need a coalition. Similarly, both Boris Johnson and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn were almost uniquely unpopular throughout the land. No prime minister has had such a poor reputation as quickly as Johnson, and no opposition leader has ever been as disliked as Corbyn. The stage, it seemed, was set for another indeterminable result.

But Boris Johnson managed it. He had a brutally simple election strategy – to keep repeating "Let's get Brexit done" - and capitalized on the political weariness of British voters. This disregarded the obvious fact that the Brexit cannot be done come January 31: There is still the trade deal to complete, and that is far from likely to be done within a year, as required by current arrangements. It was also peculiar to see the Conservatives saying that they wanted Brexit done so they could focus on what Britain needed, in health, education and so on. Leaving the EU went from being a route to the sunlit uplands to an obstacle that needed to be dislodged from the political gullet.

Staff count ballots for the general election at Brunel University in Uxbridge, London, Britain, December 12, 2019. /Xinhua Photo

Staff count ballots for the general election at Brunel University in Uxbridge, London, Britain, December 12, 2019. /Xinhua Photo

Yet the appeal worked. Voters were tired of the whole issue and an appeal to their weariness was cunningly effective. Northern and working-class seats may not have voted Conservative for generations, but they had often strong "Leave" constituencies in the referendum. And so, right across the north of England, in Wales and in the midlands, voters turned to Boris as the man to get it done.

It was not that they liked the man so much – TV interviews showed voters saying things like, "I don't much like him, but I don't like Jeremy Corbyn at all, and I just want Brexit done" - as that he managed to come second in an unpopularity contest. That was just about enough.

The Conservatives thus are celebrating their greatest election victory since the halcyon days of Margaret Thatcher in 1987. It is also their first victory with a real working majority since then (as both 1992 and 2010 saw majorities of 20 seats or less, which means small groups of backbench MPs can cause mischief). Prime Minister Boris Johnson is now unfettered, unchained, and politically dominant. He has taken a party which just ten years ago had only 198 seats out of 650 and lead it to its fourth election win in a row, against a backdrop of Brexit turmoil and popular discontent with austerity.

He has lead from the front, with few of his Cabinet colleagues much in evidence during the election campaign (Jacob Rees-Mogg in particular was noticeably invisible, but there were few signs of Chancellor Sajid Javid or Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab either).

What Johnson makes of the many opportunities that lay before him are now entirely down to him. What is peculiar is that very few people have a good idea of what that might bring. Johnson as mayor of London was mostly socially liberal, with a liking for spending on large projects, from "the Boris bus" to a garden bridge over the Thames. But as Prime Minister, he almost savagely culled former colleagues from government and introduced a notably more sharply right-wing administration.

The Conservative manifesto promised greater spending and investment, and Johnson promised after the election victory that the NHS would be a priority. But no-one knows whether to believe any of this. Johnson is not a details man. Nor has he been someone to play things straight. Political expediency, evasiveness and mendacity have so far been his only consistent trademarks.

But now it is all on him. The next five years are his. It is his great opportunity and his most severe challenge. History will judge what he makes of it.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com)