In suburbs, towns and villages of remote provinces in China, groups of young men and women are laying the groundwork for fueling China's AI boom.

Artificial intelligence (AI), despite all the hype about it, still has to be taught by humans as of today. Take facial recognition as an example. Before data is fed to the AI algorithm for training, human laborers need to label the data, to identify which part of the image is an eye, which part is a mouth. Spending hours drawing endless circles around items to categorize what they are, these overlooked people are the reason why AI can "see."

China's AI strength comes from its large quantity of data. Due to the lack of a data protection mechanism, Chinese AI firms are able to tap into a large pool of data to train their AI algorithms and thus produce AI solutions with higher precision.

Employees work on labeling different items for data collection on computer screens. /Reuters Photo

Employees work on labeling different items for data collection on computer screens. /Reuters Photo

But that explains only half of the story, said Chen Guancheng, chief technology officer of Testin, a company specialized in AI data solutions. With the expansion of AI applications, the quality of the data, rather than quantity, matters more, he told CGTN. For example, a low-quality data set provided to a facial recognition algorithm may result in a mismatch of identities.

Those human laborers hold the key to high-quality data used for AI in China. They power AI applications in industries as diverse as autonomous driving, medical diagnosis, banking, retail, and public security. They are part of a growing multibillion-dollar data labeling industry in China that serves hundreds of thousands of companies that employ AI domestically and abroad.

Most tech companies are unwilling to label the data themselves since it would be too costly to hire people to deal with a large trove of data. In general, there are two ways of data labeling operations in the industry: one is outsourcing to data labeling factories, the second is conducted in-house by professional data labelers.

While China is known for its data labeling factories where workers label images as if they are on an assembly line of manufacturing, the second type is rising in China as the demand for high-quality data grows.

An employee labels vehicles on an image on a computer screen. /Reuters Photo

An employee labels vehicles on an image on a computer screen. /Reuters Photo

Testin is one of the third-party companies specialized in in-house data-labeling service. It boasts of employing data workers as full-time office workers with access to all benefits that an office worker at IT companies are entitled to. Unlike the data labeling factories where workers are generally of lower education background and low skill threshold, Testin says it provides good training to its employees.

"Our workers know well the implications of their work, what they are doing and why they are doing it," said Chen.

The majority of data labeling projects used to come from Chinese tech giants, such as Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent. Now, as AI applications grow to cover almost every sector, requests for data labeling start to come from diverse sources, including AI startups and traditional industries like banking and retail.

According to Cognilytica, an American AI research firm, the global market for data annotation grew by 66 percent to 500 million U.S. dollars in 2018 and is set to more than double by 2023.

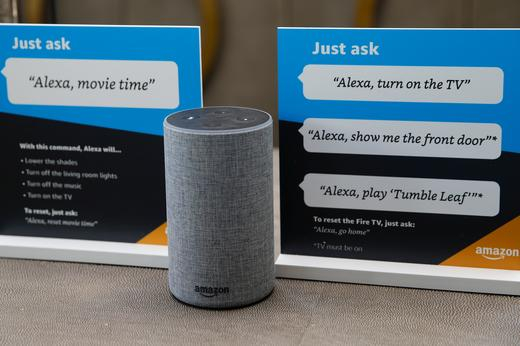

Prompts on how to use Amazon's Alexa personal assistant are seen in an Amazon experience center in California, U.S. /Reuters Photo

Prompts on how to use Amazon's Alexa personal assistant are seen in an Amazon experience center in California, U.S. /Reuters Photo

But as the industry exploded, concerns rise for data security. Facebook was once reported to employ an Indian data labeling company to go through users' private posts to label them for AI systems. Amazon's Alexa experienced a user trust dip when it was revealed that recordings of some conversations in Alexa are listened by staff members at Amazon for the sake of training speech recognition and natural language understanding.

According to an investigation by CCTV, one bundle of 5,000 facial images can be sold on second-hand e-commerce site in China for just 10 yuan (1.42 U.S. dollars). Many Chinese apps don't even have proper terms and conditions that regulate the collection of users' data.

But Chen said he is confident the data labeling industry in China is coming to terms with the importance of data security.

"The industry is still in the process of development. Supervision from the public, (the) media, and (the) government would no doubt push players in the industry to pay more attention to data security," he asserted, adding that his company has strict technical and operational safeguards, such as auto-deleting mechanism and strict consent mechanism.

A test on self-driving mode. /Reuters Photo

A test on self-driving mode. /Reuters Photo

There are already signs that humans can be cut out of the process in data labeling. Scale AI, a San Francisco-based data labeling firm, relies on algorithms to do the labeling before human labelers have a final check on their work. Since now, 80 percent of AI projects' time is spent on gathering, organizing, and labeling data, if algorithms can be trained to do the work, it would significantly increase the efficiency of AI projects.

"But we need to be aware of the limitations of AI at this present stage," Chen reaffirmed. "Now the amount of artificial intelligence we have is directly proportional to the amount of human labor we put in. The machines cannot learn autonomously as of now."

What to make of the day when humans are completely cut out of the loop of AI is still unclear. A newer form of human-machine relationship may emerge out of that context.