Editor's Note: Jimmy Zhu is a chief strategist at Fullerton Research. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

China's rising GDP per capita means greater buying power and an economy boosted not only by manufacturing but also increasingly by consumption. More importantly, a more diversified economy lays the groundwork for the country's growth to be more resilient to external impacts. Still, certain risks still need to be addressed when the economy becomes richer, including the middle-income trap which could lead to growth stagnation, inadequate income distribution and less disposable income.

China's GDP per capita is expected to reach 10,000 U.S. dollars in 2019, Chinese President Xi Jinping said on December 31 when delivering a New Year speech in Beijing. The definition of GDP per capita is calculated by dividing GDP over a country's population, so that the number represents the value attributed to each individual person.

GDP per capita is a more reliable metric for gauging a country's prosperity than GDP itself as it focuses more on the effectiveness of the productivity and consumers' spending power. Over the past few years, China has been implementing various economic and financial reforms to improve economic productivity, including state-owned enterprise reforms, a more market-based interest rate and yuan policies.

Per capita GDP usually moves in tandem with the changes to the level of wages. For example, the two countries with the highest per capita GDP were Luxembourg and Switzerland in 2019, according to IMF data. OECD statistics show that average annual salaries in these two countries are also the highest in the world. So for China, a rising GDP per capita holds the key to the pace of economic reform that is transforming the economy into being more domestic consumption-driven.

The global economy has been running out of fresh drivers to boost long-term growth since 2008's global financial crisis. Central banks around the world have become more proactive in addressing slowing growth, but such monetary policies also reduce the long-term potential growth rate as they cause inefficiencies in economic production and resource allocation.

Thus, structural reforms in China as it shifted into being a more consumption-based economy over the past decade have played a key role in the nation's GDP per capita reaching 10,000 U.S. dollars in 2019. According to the World Bank's statistics, exports only accounted for 19.5 percent of China's GDP as of the end of 2018, well below the 27.1 percent recorded in 2010.

A more diversified Chinese economy

China's GDP per capita crossing over 10,000 U.S. dollars means that spending power has also increased due to higher personal income, which allows domestic consumers to spend more than before and make the economy more diversified. Recent experience in other countries shows that a diversified economy is more resilient to external weakness.

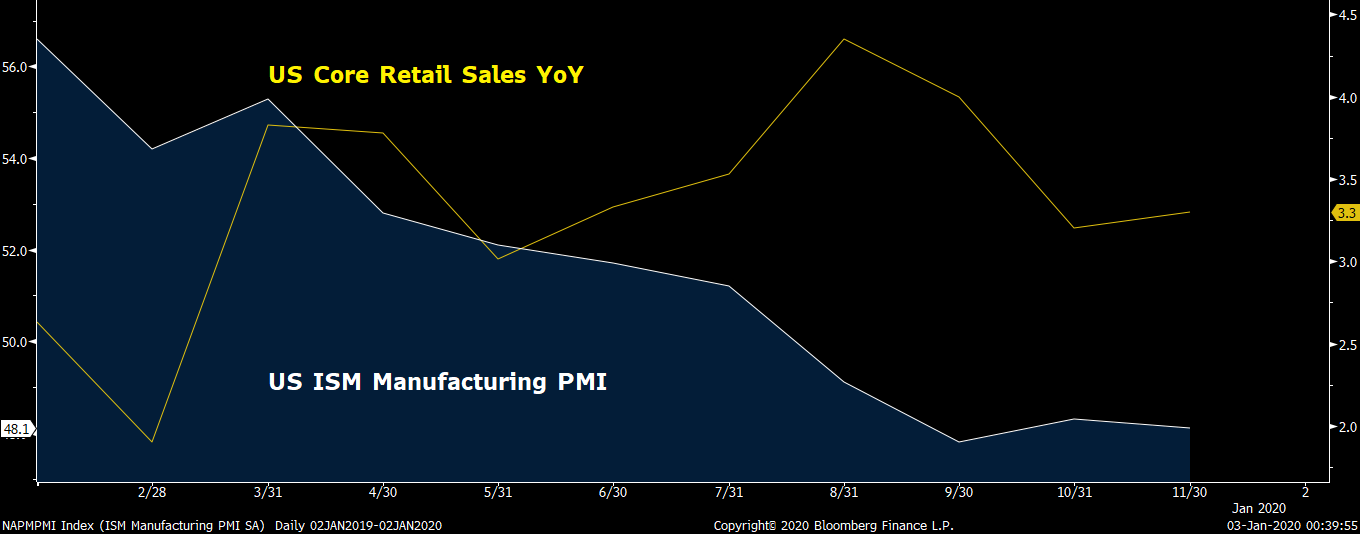

Manufacturing activities have been trending slower since the end of 2017, and growth in these sectors moved into contraction territory in the third quarter of 2019. Until today, many economies' manufacturing PMIs have risen above the key 50-level, but the U.S. ISM manufacturing remained below 50 as of the latest reading. Surprisingly, U.S. growth wasn't really affected by its recession in factory activities due to a resilient growth level in consumption.

Still, Germany wasn't lucky enough to escape a technical recession in the third quarter in 2019, when its manufacturing PMI kept falling throughout the year. Data shows that household consumption in Germany accounted for around 52 percent of its GDP, much below a 70 percent ratio for the U.S. Take note that most policymakers in the world are setting stimulus measures based on their own domestic condition, so a more domestic consumption-driven economy will be easier to recover from those policy measures.

Thanks to the rising percentage of Chinese consumption in recent years, monetary policies in China have been focusing on the domestic economic environment, paying less attention to the U.S. Federal Reserve's policies than in the past. When the Fed raised interest rates in 2018, Chinese central banks kept reducing the reserve requirement ratios to support the banks' lending to small and mid-sized business. When the Fed cut rates three times in the second half of 2019, the People's Bank of China (PBOC) didn't introduce many measures to support the economy.

Further risks associated with rising GDP per capita in China

When GDP per capita in China reached 10,000 U.S. dollars, the country could widely be considered as being middle-income. Various risks could emerge as a result, as the cost of labor loses its advantage and there is an increasing divergence in income distribution.

The first concern is that whether the economy will be stuck in the "middle-income trap", an economic development situation in which a country that attains a certain income gets stuck at that level and loses its advantage due to rising wages.

To avoid the middle-income trap, one of the best strategies is to develop technology and innovation. Many of the current projects running in China, including the Greater Bay Area plan and China's Nasdaq-style Star Market, aim to further strengthen the application of better science and technology to be used in the real economy.

More advanced technology will help enable the Chinese economy to grow more effectively, further rebalancing its economic model into a more sustainable one. In order to further increase the consumption power and achieve a higher level of prosperity, China has to avoid a situation of the middle-income trap.

The second concern would be the inadequate income distribution that leads to higher default activities. The gap between the earnings of rural people and their urban counterparts remains quite large, the same is true for different industries. Higher GDP per capita is usually equal to a higher cost of living in general, inducing those whose incomes are below the average to take riskier investment instruments to catch up on the living standard.

Once the economy enters into a downturn cycle, falling prices in these risk assets rapidly shrink those people's net assets value. Poor people are typically vulnerable to any substantial investment losses, raising the possibility of more defaults.

The third risk is less disposable income in more developed cities, restraining the levels of consumption and savings. Housing prices in top tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai are currently around five times the median. Based on our research and findings, the average disposable income in first-tier cities is around 1,000 yuan and around 1,500 yuan in second-tier cities. Less disposable income also increases debts' default probability due to fewer savings to counter any uncertainties.