Editor's note: Tom Fowdy is a British political and international relations analyst and a graduate of Durham and Oxford universities. He writes on topics pertaining to China, the DPRK, Britain, and the U.S. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

On Monday, the Pacific island nation of Kiribati signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) to join China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as its President Taneti Maamau visited Beijing. Two months ago, the country had switched "ties" from Taiwan to China and affirmed the one-China principle.

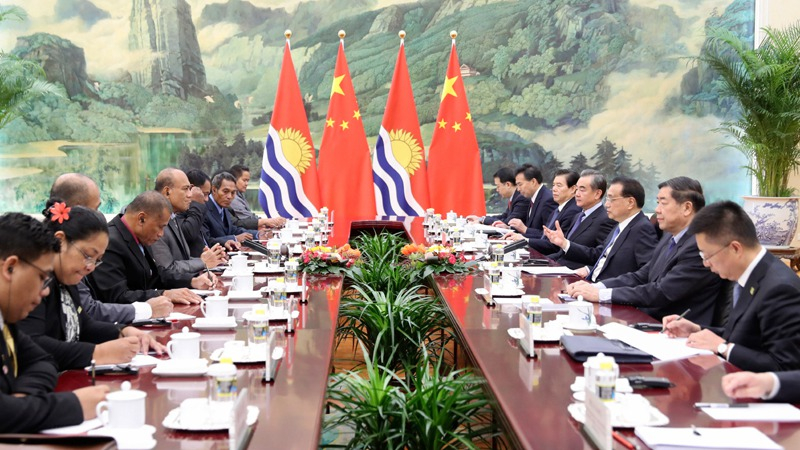

Now, on the leader's first official visit to China, the two countries have affirmed future cooperation in a number of areas including fisheries, climate change, tourism, education and infrastructure. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang spoke of the new agreement under "the framework of South-South cooperation".

But what is "South-South cooperation"? And how it is significant to China's foreign policy goals? Although Western discourse has sought to misrepresent programs such as the BRI and paint China's efforts in wholly cynical terms, for decades China's foreign policy has long been oriented towards consolidating ties with other "global South" countries, that being: developing countries that are not part of the established "West" and have been subject to colonialism.

Evolving from China's own historical experience, this takes the form of principles such as national sovereignty, non-interference in other countries' domestic affairs and mutual development. This is the preliminary logic of the BRI.

The foreign policy foundation of the People's Republic of China derives from the country's historical experience of domination by foreign powers. Since 1949, China's diplomatic outlook has shaped in a way that sees benefit in seeking solidarity with countries of a similar experience.

Former Chinese premier Zhou Enlai was decisive in shaping this position through his role at the famous Bandung Conference in 1955, whereby he created a foundation for China's relationships with Africa and Latin America.

As the Sino-Soviet split took place, the late Chinese leader Mao Zedong crystallized this into a "three worlds" theory, with the sphere of the "third world" or post-colonial world, non-aligned world standing between the respective United States and Soviet Union spheres within the Cold War system.

Although the world has since changed, this foundation nevertheless remains important in China's contemporary diplomacy and its relevance to the BRI. One may note that firstly China does not opt for formal alliances or a purposeful struggle for hegemony, and secondly post-colonial principles such as national sovereignty, equality and mutuality in relations continue to receive emphasis in diplomatic discourse.

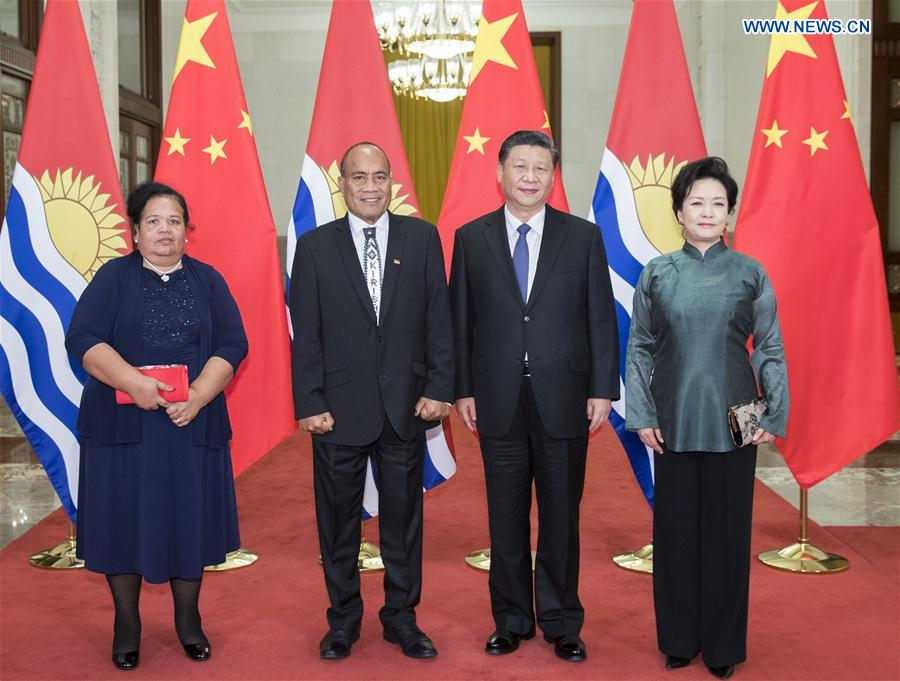

Chinese President Xi Jinping (2nd R) and his wife Peng Liyuan (R) pose for a group photo with Kiribati's President Taneti Mamau and his wife before the talks between Xi and Mamau in Beijing, capital of China, January 6, 2020. /Xinhua Photo

Chinese President Xi Jinping (2nd R) and his wife Peng Liyuan (R) pose for a group photo with Kiribati's President Taneti Mamau and his wife before the talks between Xi and Mamau in Beijing, capital of China, January 6, 2020. /Xinhua Photo

This in turn is what builds the foundation of the BRI and other development policies: China continues to seek its best interests and national goals through cooperation with similar countries, which is key to prevent domination and challenges to national sovereignty by the West.

With many developing countries having suffered from economic exploitation by Western powers, with forced Neoliberal policies having plunged Africa and Latin America into poverty in the 1980s, these nations have grown to see China as an alternative pathway to national development with much less liability, with Beijing's traditional policies allowing these countries to find empathy in the form of a common history, worldview and legacy.

On this background, nations around the world have subsequently sought to join the BRI in growing numbers and enhance economic ties with Beijing, which has allowed them to hedge their own autonomy against "traditional sources of support" in the West.

Therefore, Kiribati has opted to join the BRI program because it recognizes what it has to offer will be wholly beneficial to it.

As a small Pacific island nation with limited resources and unable to hold its own weight against Australia and the United States, ties with China do not result in its own "domination" or "subordination" as Western media misleadingly portrays it, but offers the island greater political space, support and economic opportunity accordingly. The West fails to comprehend this again and again, refusing to accept such decisions as legitimate, honest or authentic.

In summary, "South-South cooperation" is how we should understand the growth of the BRI, and China's deeper ties to the broader developing, non-Western world. This is not about power, domination or exploitation; instead it is a historically accumulative pathway whereby China has envisioned its best interests in solidarity and coordination with countries of a similar experience.

Thus, Beijing is continuing a decades old diplomatic precedent as a means to responding to modern challenges. Consequentially, as Kiribati joins, the leaders of both countries have heralded a new era of "South-South cooperation" in the view of spurring development and mutual prosperity in the Pacific.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)