Representatives from China and Pakistan sign cooperation documents during the ninth Joint Cooperation Committee (JCC) meeting of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in Islamabad, Pakistan, November 5, 2019. /Xinhua Photo

Representatives from China and Pakistan sign cooperation documents during the ninth Joint Cooperation Committee (JCC) meeting of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in Islamabad, Pakistan, November 5, 2019. /Xinhua Photo

Editor's note: Hannan Hussain is a security analyst at South Asia Center, the London School of Economics, and an author. The article reflects the author's opinions, not necessarily the views of CGTN.

2020 is a significant year for the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Beijing is preparing to send across one billion U.S. dollars in investment to kickstart the next phase of the multi-billion-dollar initiative. Meanwhile, Pakistan's civilian and military leadership continues to facilitate progress through political and diplomatic consensus.

But as with every strong collaboration, there comes uninvited hostility. Western critique of CPEC is amplifying once more, with Washington furthering fears of a "debt-trap." It is ironic that these speculations are gaining momentum at the exact time when both Islamabad and Beijing are steering the corridor towards its next phase.

U.S. academics, along with key diplomatic representatives, have started to presume the "dangers" of a successful corridor. The Trump administration's senior-most diplomat for the region began her year by declaring credible Chinese investors as "blacklisted" by the World Bank.

In truth, this allegation resonates closely with the Trump administration's earlier tirade in December. Accusations of labor exploitation and profit consolidation were hurled at Beijing in abundance, but failed to penetrate official discourse.

What Washington doesn't realize is that it cannot unilaterally dictate the fate of a sprawling connectivity corridor. More importantly, it must never attempt to downplay the merits of a long-standing China-Pakistan cooperation, which has driven peace and stability in South Asia.

For instance, Ms. Alice Wells, the top U.S. diplomat for South Asia, lashed out at the credibility of Chinese firms without listing any specific companies that fell within this "blacklisted" bracket. Similarly, the West's critique of CPEC is weakened by the fact that the corridor's total contribution to Pakistan's debt is only 4.9 billion U.S. dollars, as confirmed by Pakistan's foreign minister.

Interestingly, it is easy to understand why Washington and its fellow skeptics in New Delhi would take a contrarian view of the CPEC. First, U.S. itself has an extremely unreliable record as Pakistan's "all-weather ally." It likes to think that its criticism of the corridor is in Islamabad's interests. But wide-ranging threats by State Secretary Mike Pompeo, along with past attempts to block Pakistan's IMF loans, suggest a completely opposite reality.

In fact, CPEC's vision of win-win connectivity is bad news for Washington's larger strategic imperatives in South Asia: To prioritize New Delhi's non-alignment with CPEC, and help facilitate Washington's "containment" of the Belt and Road Initiative.

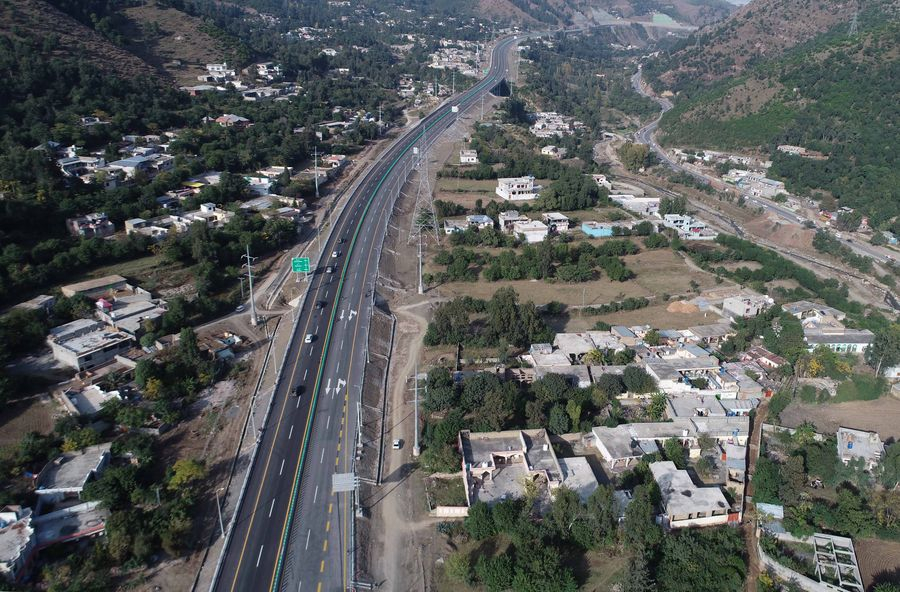

The expressway section of the Karakorum Highway (KKH) project phase two was inaugurated in Havelian in northwestern Pakistan, marking another step forward to complete the early harvest project under the CPEC, November 18, 2019. /Xinhua Photo

The expressway section of the Karakorum Highway (KKH) project phase two was inaugurated in Havelian in northwestern Pakistan, marking another step forward to complete the early harvest project under the CPEC, November 18, 2019. /Xinhua Photo

Moreover, the West's "security-centric view" of South Asia just does not hold true for CPEC's core purpose. Last month, Mr. Yao Jing, the Chinese Ambassador to Pakistan, categorically declared CPEC as a commercial undertaking with no link to security cooperation.

Speaking at a national conference, Mr. Jing said that the second phase of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) would help Pakistan achieve its "economic objectives." Neither Mr. Jing, nor Dr. Moeed Yusuf, Prime Minister Imran Khan's Special Assistant on National Security and Strategic Policy Planning, underlined a security aspect to CPEC.

This myth of CPEC as a "security tool" appears to sell only within the strategic confines of Mr. Trump's leadership.

It is also worth noting that the U.S. has mobilized many of its protectionist allies across Europe and South Asia, in a bid to generate skepticism over the landmark China-U.S. trade deal. This is important, because the timing of the campaign overlaps with Washington's renewed criticism of phase-two CPEC projects.

The U.S. has also employed the same craft to undermine Pakistan's counter-terrorism gains under the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). These gains are a reality which Beijing has consistently backed. Yet only Washington and New Delhi continue to raise red-flags.

Together, these counter-terrorism and anti-trade offensives reveal the difficulties Washington is facing in portraying the CPEC as a security and strategic initiative. Should it find any success, the Trump administration would spare no time in deliberating the containment of the CPEC, and by extension, the BRI itself.

From a factual lens, New York's Rhodium Group published a comprehensive analysis detailing China's 40 debt renegotiations across 24 countries last year. Its findings proved that asset seizure, let alone debt-trap, was extremely rare.

In what serves as a data-intensive rebuttal to the Trump administration's CPEC hardline, the analysis argues that China's "debt renegotiations usually involve a more balanced outcome between lender and borrower, ranging from extensions of loan terms and repayment deadlines to explicit refinancing, or partial or even total debt forgiveness."

All of these findings are not part of Washington's official discourse for one simple reason: Acknowledging facts means supporting CPEC's promise. That is a possibility devoid of both preference and precedence from Washington.

Currently, the CPEC is building upon multi-sector projects under phase-two operations. These multi-sector projects are aimed at generating mass level employment opportunities in Pakistan, by leveraging industrialization, agriculture and socioeconomic avenues.

Both Beijing and Islamabad are also working together to accelerate the 9.2 billion U.S. dollars Mainline-I CPEC project, with over 11 billion U.S. dollars' worth of projects achieving completion already. Ambassador Yao Jing also indicated China's promotion of the "business and manufacturing nexus" – an effort to bolster Pakistan's cross-sectoral partnerships.

With consistent state-to-state progress, there is zero chance for Western "debt-trap fallacies" to make gains with China and Pakistan. Instead, Washington should appreciate CPEC's opportunities for regional cooperation and win-win connectivity. Saudi Arabia, Iran and Malaysia are some countries that have opened up to these prospects in recent times.

Washington's recourse to hostility will be nothing but a futile exercise.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com)