Editor's note: Djoomart Otorbaev is the former prime minister of the Kyrgyz Republic and a distinguished professor at the Emerging Markets Institute of Beijing Normal University. He is also a physics professor. The article reflects the author's views, and not necessarily those of CGTN.

What was the most important event in 2019? Climate change, forests fires in the Amazon, Australia, California, etc., a chain of street protests all over the world, the impeachment of President Trump, tensions in the Persian Gulf? Yes, all of them grabbed the world's attention in 2019, but it's probably hard to pinpoint one that "stands out" from the rest.

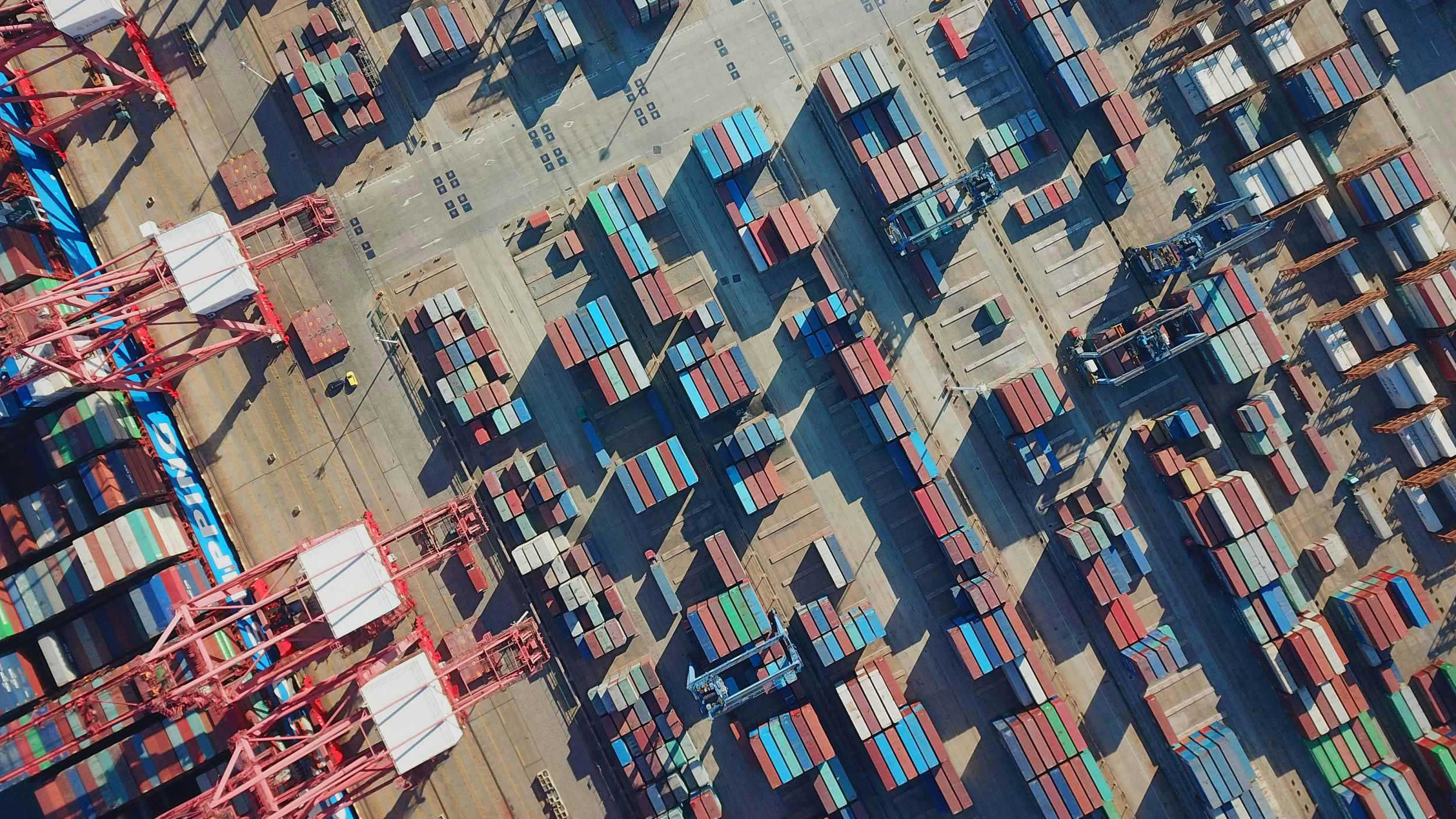

However, many would agree that in the economic sphere, the U.S.-China trade tensions were perhaps the most intense. The "war of tariffs" has by far had the most damaging effect on the world economy, which brought fundamental uncertainty to the global economic scene. It has become the main source of turbulence and nervousness regarding global markets, the main reason for the slowing down of the world economy.

Moreover, the frictions were not only unfolding in trade. They were especially noticeable in the areas of science and technology with some calling it the "technology arms race" between China and the U.S.

On January 15, and after almost two years of tit-for-tat, the U.S. and China finally signed a phase-one trade deal. But it only covers the easiest aspects of their relationship and only removes some of the tariffs. With the signing of this agreement, there was an obvious separation between the trade disputes and high-tech competition. Most of the analysts predict the pressure on Chinese high-tech companies will continue in the foreseeable future.

In 2020, being tough on China will become even more "fashionable" and easy political sell in the U.S., especially considering the upcoming presidential elections. The case of U.S. discrimination against Huawei is just one example.

The U.S. administration was even said to be looking at rules against "sensitive" U.S. investments in China, something that was once nearly unthinkable in the free market. Washington clearly has toughened oversight of Chinese investments, banned U.S. firms from doing business with advanced Chinese companies and increased criminal prosecution of alleged technology theft. As a result, now U.S. and Chinese firms doing business with each other have become much more cautious.

Chinese investments in the U.S. in 2019 dipped to 3.2 billion U.S. dollars, its lowest level since 2011, according to the American Enterprise Institute report. Meanwhile, U.S. investment in China in 2018 dropped to 13 billion U.S. dollars, according to independent China research team Rhodium Group.

High-profile Chinese firms, like the insurance giant Anbang and Kai-Fu Lee's Sinovation Ventures, have reportedly either sold or scaled back their U.S. operations, while many, including Huawei and ZTE have suffered visible losses after being subject to U.S. bans.

Chinese Vice Premier Liu He stands with U.S. President Trump after signing the trade agreement at the White House in Washington, DC, U.S., January 15, 2020. /Reuters Photo

Chinese Vice Premier Liu He stands with U.S. President Trump after signing the trade agreement at the White House in Washington, DC, U.S., January 15, 2020. /Reuters Photo

Many more events brought even thicker clouds to the future for U.S.-China relations. For example, in terms of scientific research collaboration, many Chinese-American scientists were accused of illegally transferring technologies from the U.S. to China. In June 2018, the U.S. government reduced the duration of visas from five years to one year for Chinese students who specifically study robotics, aviation and high-tech manufacturing in the U.S.

In August 2018, the U.S. National Institutes of Health sent a letter to more than 10,000 institutions warning about some "foreign entities" interfering in biomedical research in the U.S.

In January 2019, the U.S. Department of Energy banned its employees and grant recipients from participating in talent-recruitment programs run by "sensitive" countries – meaning China. In April 2019, a few ethnically Chinese scientists were ousted from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center because of their undisclosed links with China. On January 28 this year, the U.S. Department of Justice announced that three scientists, including Professor Charles Lieber, chair of Harvard University's chemistry and chemical biology department, have been charged in connection with illegal scientific links with China. The U.S.-China conflicts quickly spread to other parts of academic exchanges.

The U.S. government is demanding universities to rearrange their relationships with Chinese partners, threatening to cut funding, restrict student and teachers visas. No doubt, the trend towards a bigger and deeper "decoupling" of the two countries' tech supply chains will go on, and the "technology arms race" will continue.

What was also new in 2019 was the spread of the global mistrust between two countries to the offices of international financial institutions (IFI). On December 6, President Trump called for the World Bank to stop lending money to China, a day after the institution adopted a lending plan to Beijing despite U.S.'s objections.

Why is the U.S. President so upset about this issue? What is the answer to this puzzle? First of all, China doesn't need cash. With its GDP, which is more than 14 trillion U.S. dollars, and foreign currency reserves that exceed 3 trillion U.S. dollars, the allocated amount is really marginal. What China needs from the World Bank and other IFI's with which it still cooperates is the "transfer of knowledge."

The U.S. President's personal intervention clearly shows that he and his advisers are furious about the transfer of any additional knowledge to China.

The chain of events clearly shows that China shouldn't have any doubt that the U.S. is currently in a new "Cold War" with China in a wide range of areas, particularly in the areas of science and technology.

How should China respond to the increasing pressure coming from the U.S.? I will illustrate in the second part of the article: China urgently needs to nurture top natural science talents.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)