When vice chairman of Kissinger Associates Joshua Cooper Ramo wrote in his op-ed that the coronavirus is a test not just for China but the whole new, connected world, he became the latest outsider to justify China's effort in fighting the disease outbreak. Over the past month, global sentiments toward China and its government at all levels have been delicately changing from being offensive and denunciatory to one of empathy and concern.

From the tagline "coronavirus Made in China" on the cover of a Der Spiegel issue to the headline "Sinophobia won't save you from the coronavirus" on Al Jazeera, from French tabloid Le Courier Picard's "Alerte jaune" (Yellow alert) to strangers hugging a girl holding a placard reading "Hug me! I'm not a virus," rationality in the global media discourse is emerging out of the nationalism, racism, politicization and xenophobia that have come about from the panic caused by the constant reports on the coronavirus in this super-connected world. As time goes by, we are also seeing the best in people in the worst of times.

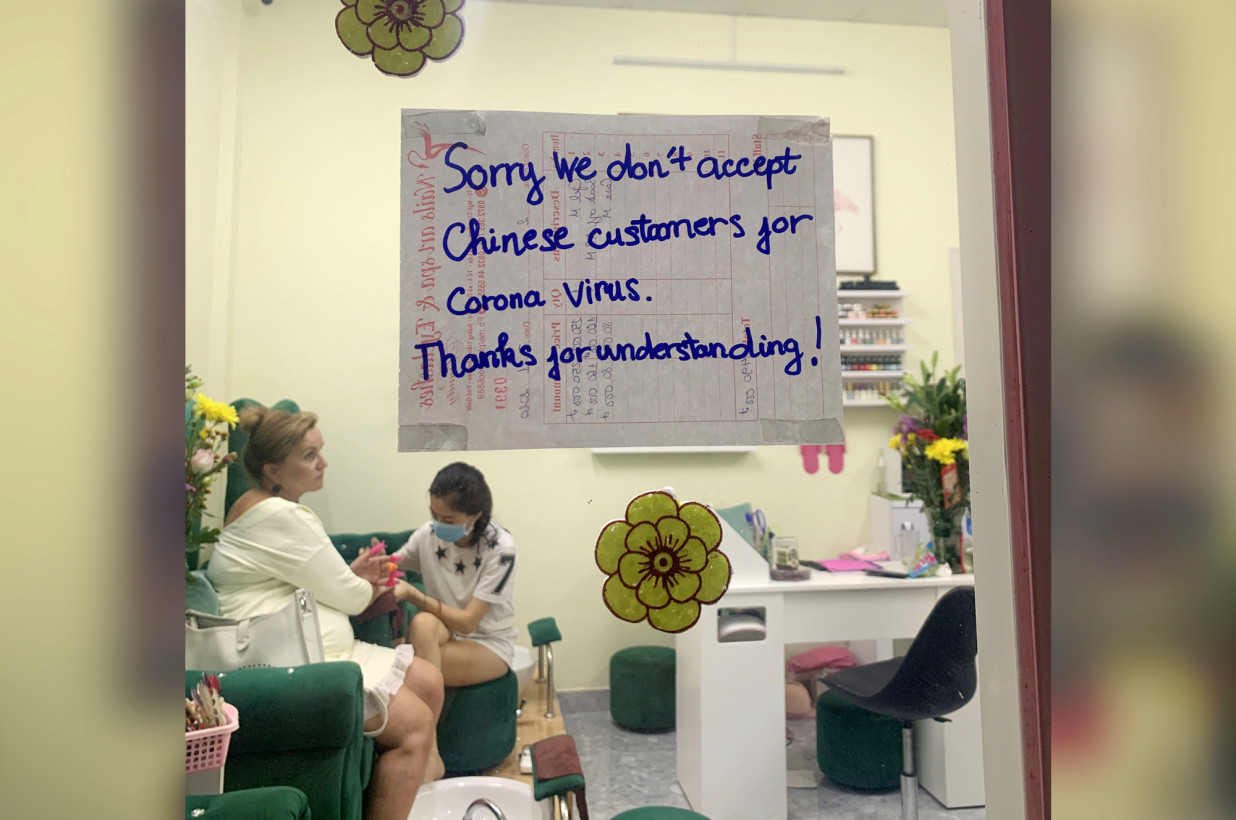

A sign which says the shop is not accepting Chinese customers because of the coronavirus is seen on the front door of a nail bar in the island of Phu Quoc, Vietnam. /Reuters Photo

A sign which says the shop is not accepting Chinese customers because of the coronavirus is seen on the front door of a nail bar in the island of Phu Quoc, Vietnam. /Reuters Photo

These past two weeks have been a masterclass in on-the-ground reporting. Since the coronavirus outbreak caused mass paralysis in cities throughout China, several of my colleagues have been reporting in Wuhan – the epicenter of the outbreak – while I stayed in Beijing interviewing people who have to soldier on despite their fear and self-doubt in order to keep the megacity running. Moving around the Chinese capital has not been easy, not only because of the limited number of taxi and DiDi drivers left during the extended Spring Festival holiday, but also due to the bone-chilling winds and snowfall plaguing the waning days of winter.

Even with the eerie calm that has descended on the usually bustling Chinese capital — with many cloistered in their homes for fear of catching the coronavirus — some are still out and about because the show must go on. From the deliveryman who has to serve over 80 households each day to the auntie who continues to screen residents who may have the infection even after breaking her arm, there is a sense of community in trying to persevere in the face of adversity.

A retired bus driver who volunteered to help screen residents at a checkpoint of a compound in Beijing /CGTN Photo

A retired bus driver who volunteered to help screen residents at a checkpoint of a compound in Beijing /CGTN Photo

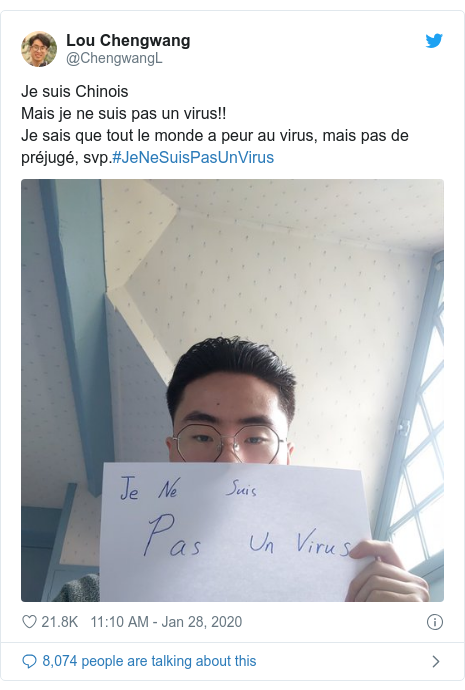

The media focus has understandably been on the number of people who have been infected by the novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19), where it's spreading to, and the amount of new confirmed and suspected cases. More striking are the reports of Chinese and other people of Asian descent who are suffering from discrimination — both subtle and blatant — because of deep-seated xenophobia and historical biases.

From schools to the workplace to even restaurants in ubiquitous Chinatowns the world over, there is the notion that this virus is a "Chinese disease" in the ugliest sense of the term. Chinese and other Asians are considered by some people to be unclean, with social media posts and videos lambasting the people for their culinary tastes and sense of hygiene.

Screenshot of tweet from user @CHENGWANGL

Screenshot of tweet from user @CHENGWANGL

Despite these disheartening instances, there have been more consequential acts demonstrating that we are ultimately a global community. Japanese organizations have held fundraising campaigns to get money and equipment to medical personnel in areas hit hard by the coronavirus, including the ground zero city of Wuhan. The Japanese Education Ministry even urged parents to teach their children not to discriminate against their Chinese peers. Americans are donating masks and other much-needed medical supplies to Chinese organizations, cleaning out the stocks of large U.S. retailers such as Walmart and Home Depot. Overseas Chinese are raising money en masse through online campaigns and through local cultural organizations so that their brethren in China can tackle this crisis.

Along with the inspiring acts come reassuring changes in tones of global media coverage, like the commentary by Ramo in the Los Angeles Times. He called on more people to be aware of the perils of the panic spreading faster than ever in this connected age. There's no denying that for a month now, it's been more of a panic epidemic than a disease epidemic given the deluge of conflicting information. In a conversation published a few days ago, Alex Traub of the New York Times talked to the publication's science reporter Donald G. McNeil Jr. who's covered SARS, MERS, the H5N1 bird flu, Zika... and now the coronavirus. He calls for the need to spread truth instead of panic during reporting. In this fight against the disease outbreak, we are seeing how our journalism is progressing from scorn and criticism to empathy and humanity.

Read more: The panic epidemic in the coronavirus outbreak

During the time of fear and uncertainty, the helping hands who selflessly put their lives on the line, the reporting of different narratives, and regular people trying to go about their daily lives are an encouraging reminder that we are all in this together. Labeling the novel coronavirus a "Chinese disease" or singling out those of Chinese descent is counterproductive in containing its spread and treating infected individuals.

There should not be an "us vs. them" mentality in a world that is connected, not only economically, but through personal and professional ties that transcend national borders. Fear of the unknown is understandable but should not be used to justify acts of discrimination. Empathy at times like this is difficult to muster — but doing the right thing has never been easy.

(Zeng Ziyi contributed research to the article.)