Egypt's former president, Hosni Mubarak, has died at the age of 91.

His funeral, held briefly after his death, received full military honors on President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi's orders.

Seen by many as a ruthless autocrat, Mubarak was forced to resign as president when the grassroots, homegrown Egyptian revolution reached its peak in February 2011.

But as unpopular as Mubarak was, his downfall did not immediately seal his fate. Unlike Muammar Gaddafi who was brutally executed by Libyan opposition forces, what accompanied Mubarak's final years was a set of much more dignified arrangements.

Egypt's President Hosni Mubarak addresses the opening session of the annual conference of the National Democratic Party in Cairo, October 31, 2009. /Reuters

Egypt's President Hosni Mubarak addresses the opening session of the annual conference of the National Democratic Party in Cairo, October 31, 2009. /Reuters

At first, it appeared he was even allowed to spend his retirement days in the comfort of a grandiose villa in Sharm al-Sheik, a Red Sea Resort. But mounting pressure coming from Egypt's public reversed the authorities' decision. Insistence that he be put on trial to answer for corruption and the harsh measures he took against protesters led to the arrest of Mubarak and his family. Deemed too sick to stay in prison, Mubarak was remanded to a military hospital and spent his final years there.

According to an Egyptian journalist who requested anonymity because he is not allowed to talk with journalists from other news agencies, the military, arguably the real source of power in the country, removed Mubarak with a promise not to persecute him as he was not only previously a part of the armed forces but also had led a successful campaign against Israel in 1973. "One of the guiding principles proliferating among the ranks of the Egyptian army was not to disrespect the elder as well as those who had great achievements in the past," the Egyptian journalist explained.

The uprising, albeit free of any political manipulation and foreign intervention, would not have succeeded without the military stepping in at the last minute.

In the years preceding Mubarak's removal, the Egyptian president did not enjoy a good relationship with the military top echelons, or the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. "Mubarak tried to flirt with the idea of making his son Gamal as his replacement but that displeased many army officers, ultimately causing a breakdown in the relationship between the two sides," The Egyptian journalist, who also lent his support to the revolution, told CGTN. "But this was not to overshadow the key role the Egyptian masses had played." Signs of civil unrest were already displayed in the streets years before the uprising, with the Mahala Labor Movement in 2008 planting the seeds that would later grow into a full-fledged revolution. "People were angry at the security establishment, frustrated over the lack of employment opportunities, and most importantly, clamoring for democracy."

Mubarak's entry to politics was largely thanks to his rise among the ranks in the Egyptian army. He joined the Egyptian Air Force when he was 19 years old and became its commander-in-chief in 1972. He would then lead a successful air campaign against Israeli troops in Sinai during the October War, one of the most rewarding warfare led by Mubarak's predecessor, Anwar al-Sadat. The momentum it achieved not only cheered and electrified Egyptians for years but also paved the way for peace between Egypt and Israel.

With reports detailing Mubarak's military achievements coming to surface in later years, applauds and commendations began to converge around him and the title "national hero" was pervasively used to refer him.

As the war was also one of the monuments that defined Sadat's success, the air force commander was soon made vice president by Sadat.

In October 1981, Sadat was assassinated by Islamic fundamentalists and Mubarak automatically became president.

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat (R) and Vice President Hosni Mubarak sit on the reviewing stand during a military parade just before soldiers opened fire from a truck during the parade at the reviewing stand, killing Sadat and injuring Mubarak, October 6, 1981. /AP

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat (R) and Vice President Hosni Mubarak sit on the reviewing stand during a military parade just before soldiers opened fire from a truck during the parade at the reviewing stand, killing Sadat and injuring Mubarak, October 6, 1981. /AP

As the aura of his widely venerated predecessor had not yet dissipated, expectations for the reticent, lackluster-styled figure ran extraordinarily low. The newly inaugurated president was perceived by many as hanging on by a thread at a time when the country was rife with desperate poverty and much emboldened Islamist militancy.

But it was exactly this flattened, uncharismatic man that would become Egypt's longest-serving president.

One of the major challenges confronting Mubarak was the sharp rise of Islamic radicalization, a stream of thoughts that was spearheaded by the radical arm of the Muslim Brotherhood and inspired the Sadat's assassination.

As a grass-roots Islamist organization that has been posing an existential threat to almost all Egyptian regimes to date, the Brotherhood is considered as the roots of Islamic extremism. In spite of the brief periods in which it caught brief reliefs, members of the Muslim Brotherhood have been perennially persecuted from Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt's most popular leader, to the incumbent President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

Mubarak's rule was no exception.

The emergency law, an extrajudicial arrangement put in place as a response to the calamitous assassination and maintained throughout Mubarak's tenure, helped usher in a repressive dynasty of arbitrary arrests and inordinate tortures. The notorious security apparatus, which was granted excessive operational powers thanks to the law, pointedly highlighted Mubarak's ruthlessness against dissension, and more specifically the Muslim Brotherhood.

But in an attempt to assuage increasingly widespread Islamist demands, Mubarak showed restrain in his cracking down on the organization and allowed a certain degree of freedom for its activities. "The Muslim Brotherhood admitted on many occasions that they had reached a clandestine deal with Mubarak," the Egyptian journalist said. "A predetermined number of Brotherhood members were allowed to become parliamentarians and its civil activities were partially restored, whereas under Sisi's rule, anyone affiliated with the organization would be treated as terrorists, which has led the Brotherhood to regret its decision to participate in the 2011 uprising."

Nevertheless, Mubarak's oppressive policies did not end there. Dissents from other social components continued to be arrested and tortured.

Mubarak's tightened grip over the country received very little attention from the Western community. This was largely due to Mubarak's perpetuation of the pro-Western policies pioneered by Sadat. The West, with the United States taking the lead, was extravagantly appreciative of Mubarak's commitment to the 1978 peace treaty with Israel. Such gratitude was explicitly demonstrated by the enormous economic aid the U.S. was sending Egypt annually in the three decades of Mubarak's reign. As he himself had correctly portrayed, his regime was indispensable to the West.

U.S. President Barack Obama (R) meets with Mubarak in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, September 1, 2010. /Reuters

U.S. President Barack Obama (R) meets with Mubarak in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, September 1, 2010. /Reuters

Egypt under Mubarak also became much less ambitious in terms of its power projection in the region. Some argue it was due to his focus on domestic stability, but positioning himself as an innocuous yet valuable ally to the regional leaders was certainly another consideration that propelled him to do so.

The desire to keep Mubarak as the head of Egypt was particularly felt in Israel. According to a Haaretz news report, Israeli intelligence paid extremely close attention to his health, meticulously dissecting every cough, hospitalization, and unexplained absence from public events.

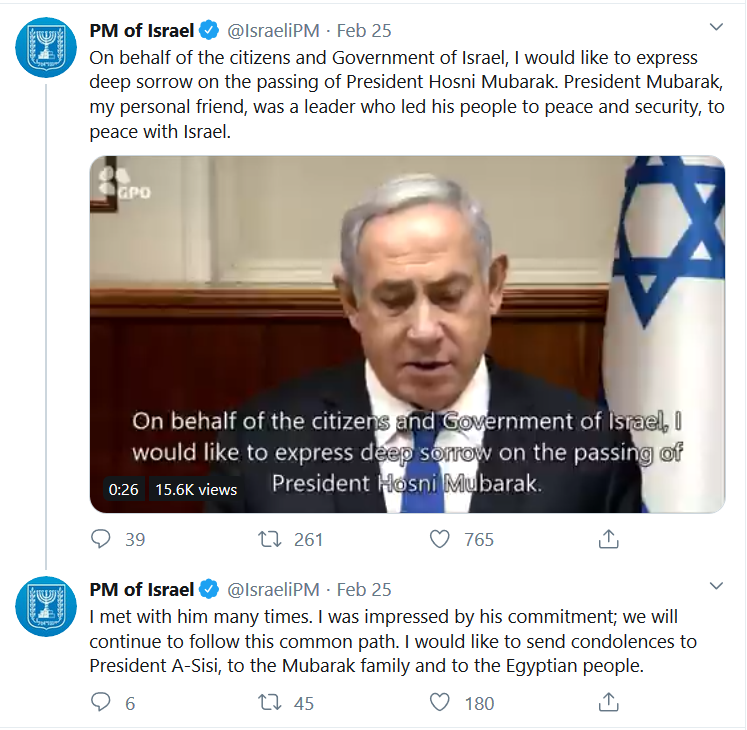

CGTN screenshot of Twitter shows Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's eulogy for Hosni Mubarak's death.

CGTN screenshot of Twitter shows Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's eulogy for Hosni Mubarak's death.

By also projecting himself as a strong bulwark against the entrenchment of Islamist activism, Mubarak benefited a great deal from enhanced cooperation with both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, the two Gulf states which viewed the Muslim Brotherhood with the same level of apprehension as Cairo.

Scrambling to boost Egypt's economic prosperity, Mubarak set in motion a series of economic reforms but only to be proven futile as they were largely restricted to privatization attempts. While macroeconomic indicators appeared healthy in the final years of his rule, the ingrained level of poverty, the unabated rates of unemployment, and the rampant practices of corruption were among the more subtle woes that affected ordinary people and continued to plague the country.

Overall, Mubarak's tenure was characterized by manifold domestic failures that would result in the demise of his regime as well as robust alliances with dominant powers both world- and region-wise which would keep any foreign opposition at bay.

Comparison to be made between Hosni Mubarak and Abdul Fattah el-Sisi is not entirely unappealing.