After weeks of delay and faulty test kits, the U.S. is now scaling up capacity to conduct COVID-19 testing.

At a press conference on Wednesday, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence announced that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is going to lift all restrictions on COVID-19 testing. Any American can be tested for COVID-19 subject to doctors' orders, according to Pence.

The need for testing became urgent as the first COVID-19 patient with no travel history and no exposure to confirmed cases was identified last week. The patient, admitted to the hospital on February 19, was not diagnosed until February 23. The request to get him tested was denied repeatedly because he did not fit the existing CDC criteria for testing.

Most labs follow a stringent criteria that the CDC set up to determine who could be tested. Before the first case of unknown origin was reported, only those who had traveled to China in the past 14 days of developing symptoms and those who had contact with coronavirus patients were eligible for testing.

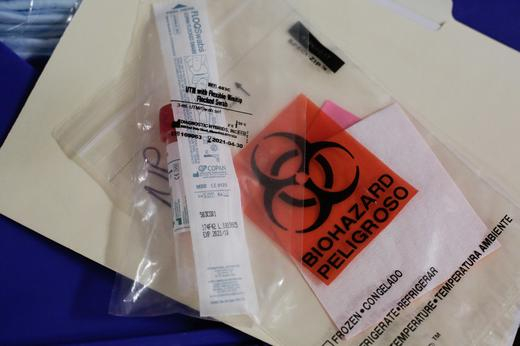

A swab to be used for testing novel coronavirus is seen in the supplies of Harborview Medical Center's home assessment team, Seattle, Washington, U.S., February 29, 2020. /Reuters

A swab to be used for testing novel coronavirus is seen in the supplies of Harborview Medical Center's home assessment team, Seattle, Washington, U.S., February 29, 2020. /Reuters

Data from the CDC shows that as of March 1, one in one million were tested for COVID-19 in the U.S. In comparison, in South Korea, it was 2,138 per million, and in Italy, 386 per million.

The high bar set for COVID-19 testing meant that those with mild symptoms were denied access. In a hearing with officials from the CDC, Senator Patty Murray from Washington state, where all the six reported deaths of coronavirus infection are from, voiced the frustration she had felt from people in her home state.

"I am hearing from people who are sick, who want to get tested, are not being told where to go. I am hearing even when people do get tested and is very few so far, the results are taking way longer to get back to them."

In the early weeks of the coronavirus outbreak, only U.S. state public labs were allowed to conduct COVID-19 testing. Local hospitals, if they wanted to test for the virus, needed to validate their test with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a lengthy onerous process that is likely to take a few days.

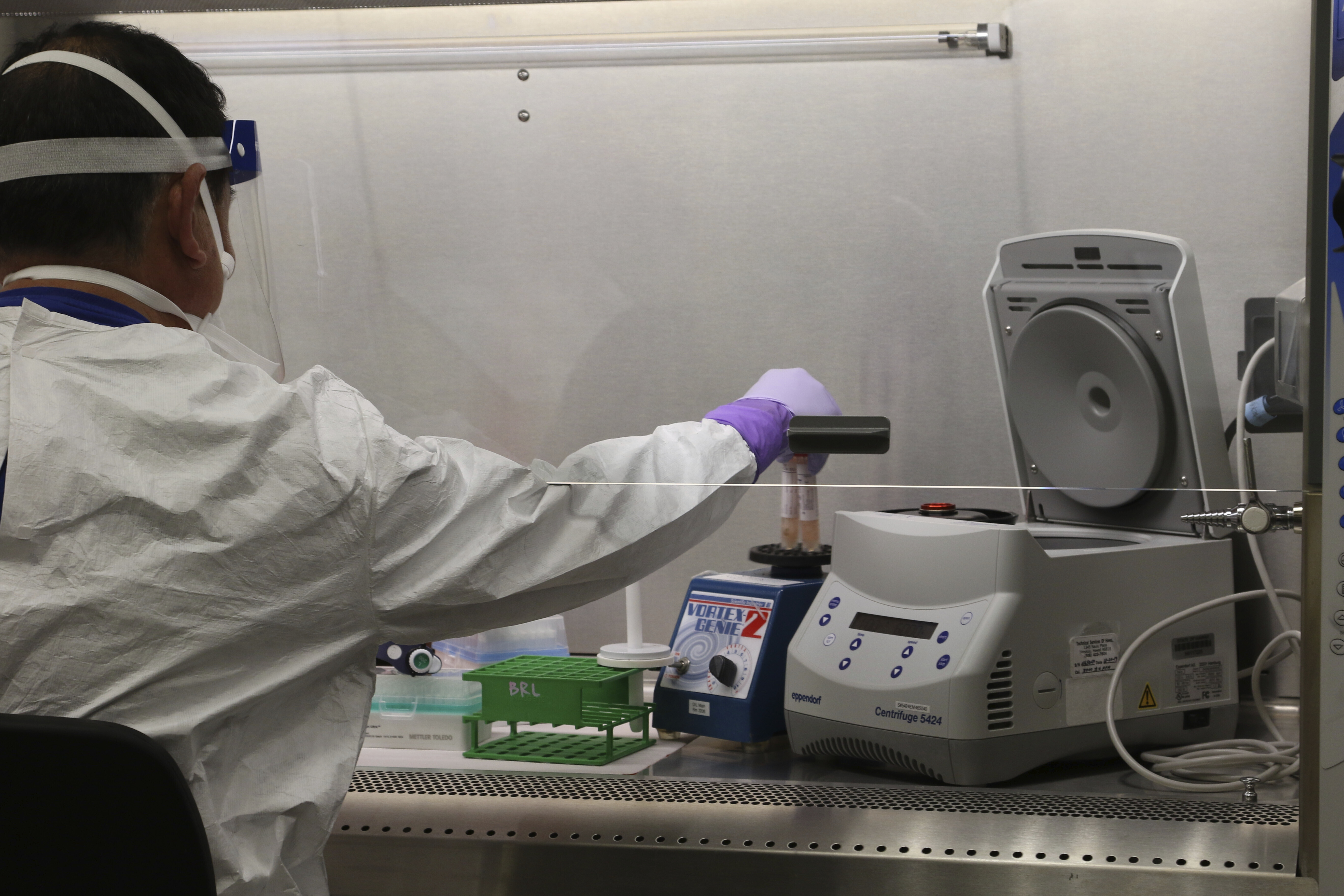

Hawaii state Department of Health microbiologist Mark Nagata demonstrates the process for testing a sample for coronavirus at the department's laboratory in Pearl City, Hawaii, March 3, 2020. /AP

Hawaii state Department of Health microbiologist Mark Nagata demonstrates the process for testing a sample for coronavirus at the department's laboratory in Pearl City, Hawaii, March 3, 2020. /AP

As of Tuesday, 54 state and local labs had the ability to test for the virus across the country, with the capacity to test 100 patients a day, according to the Association of Public Health Laboratories, which represents state and local laboratories.

Faulty test kits also delayed public health officials' response. The 200 test kits sent by the CDC in early February to public health labs were later announced to be flawed. All samples were required to be sent to the central CDC headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, which significantly delayed the diagnosis and treatment process.

"Coronavirus testing kits have not been widely distributed to our hospitals and public health labs," said Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York. "Those without these kits must send samples all the way to Atlanta, rather than testing them on site, wasting precious time as the virus spreads."

A delay in testing means the virus may now be circulating undetected in communities across the country, which significantly increases the likelihood of cross-infection. Darcy Burner, a businesswoman and politician in the Eastside suburbs of Seattle, wrote on Twitter that in her neighborhood, local hospital isolation rooms are full of COVID-19 patients who have not been reported.

A cafeteria sits vacant at Saint Raphael Academy in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, after two people who returned from a school trip to Europe tested positive for the new coronavirus disease, March 2, 2020. /AP

A cafeteria sits vacant at Saint Raphael Academy in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, after two people who returned from a school trip to Europe tested positive for the new coronavirus disease, March 2, 2020. /AP

"The people who aren't hospitalized are currently spreading the virus largely unchecked, and right now have no way to get tested," she wrote.

The Association of Public Health Laboratories, in a letter to FDA, called for the agency to expand the number of eligible labs and allow labs to develop their tests so that more testing for COVID-19 can be conducted.

"While we appreciate the many efforts underway at CDC to provide a diagnostic assay to our member labs … this has proven challenging and we find ourselves in a situation that requires a quicker local response," said the letter.

Following the nation-wide call for more testing, and as the fear of community transmission increases, the CDC began shipping test kits to private labs across the country. Hundreds of academic hospital labs are authorized to offer coronavirus testing, while commercial companies are also encouraged to develop their own testing kits.

Police deliver groceries to Kirkland Fire Station 21 where firefighters are in quarantine following their response to coronavirus cases in Kirkland, Washington, March 2. /Reuters

Police deliver groceries to Kirkland Fire Station 21 where firefighters are in quarantine following their response to coronavirus cases in Kirkland, Washington, March 2. /Reuters

2,500 test kits with a capacity of up to 500 tests each will be supplied to laboratories by the end of Friday, able to perform up to one million coronavirus tests, according to FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn.

But as the availability of test kits increase, costs associated with the tests also become a problem. Those with medical insurance can have their testing cost covered just as other type of care. For tests conducted in public labs, no cost will be incurred. But as the CDC announced that it would work with commercial firms to expand testing, private companies may issue separate bills for the test.

But even if testing is free, other associated costs may not be. The U.S. health care system has already come under fire in recent days for charging hefty bills for government-mandated quarantines. According to the New York Times report, among a dozen Americans flown back from Wuhan and quarantined in the U.S., one was charged for over 3,000 U.S. dollars for his hospital visit.

For the 27.5 million uninsured in the U.S., they may have no choice but to foot an exorbitantly high medical bill, including costs of visiting the doctors' office and emergency room cost. The concern is that the uninsured would skip treatment for fear of its overwhelming cost and thus miss the chance for early treatment.

Women and children walk past personnel in protective clothing after being evacuated from Wuhan, at March Air Reserve Base in Riverside County, California, January 29. /Reuters

Women and children walk past personnel in protective clothing after being evacuated from Wuhan, at March Air Reserve Base in Riverside County, California, January 29. /Reuters

On Wednesday, New York became the first state in the U.S. to waive patients' out-of-pocket costs associated with testing for the virus, e.g. emergency-room visits costs, visits to in-network urgent care and physicians' offices. There are now more calls for Congress to help fund local response and research for treatment for COVID-19.

It is increasingly the case that the burdens of COVID-19 are falling disproportionately on those who are vulnerable because of their economic, social and health status. To remove the financial barrier for people to go and get screened at the hospital would be key to containing the spread of the virus.