Throughout China's battle against COVID-19, Chinese scientists and health authorities have worked closely with other countries and the World Health Organization (WHO) and shared the country's experience with relevant stakeholders.

Recognition of China's efficiency in containing the spread of the new coronavirus and support from the international community have flooded press conferences throughout the COVID-19 outbreak.

The WHO in particular has spoken highly of China's contribution to disease prevention and control. "China's efforts have bought the world time – even though those steps have come at greater cost to China itself," said Director-General of WHO Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

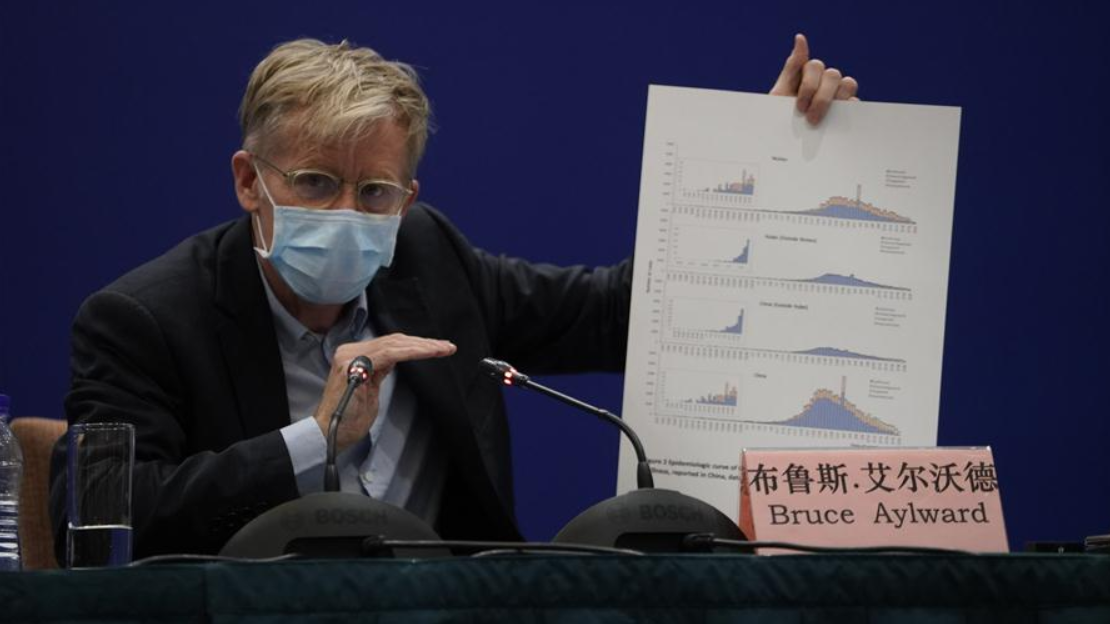

Dr. Bruce Aylward, the WHO's deputy chief, who led an advance team to visit China in February, has on many occasions lauded China's efforts in tackling the situation.

He gave very specific answers as to why China is applaudable, pointing out that the measures taken to deal with the epidemic in different regions were "tailored" to avoid resources being exhausted. The "aggressive" and "old-fashioned" approaches could teach the world a valuable lesson, he said.

In one of his remarks, Aylward also said he would want to be treated in China if he ever caught the disease.

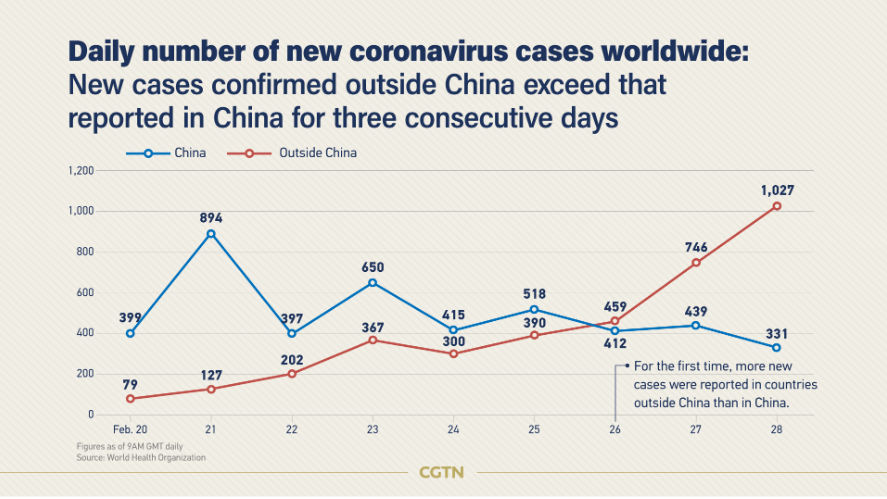

On Wednesday, Aylward was interviewed by The New York Times and he offered a meticulous account of his observations in China. The interview came as new cases of coronavirus have dropped sharply in China and those reported outside the country began to exceed the ones confirmed domestically.

When asked whether cases in China were really going down, Aylward said the testing clinics saw a drastic drop in people coming in requesting tests and "hospitals had empty beds," adding that he found no evidence indicating manipulation of numbers.

He said China reorganized its medical response by moving "50 percent of medical care online so people didn't come in." Prescriptions like insulin or heart medications could all be prescribed and delivered online and those who displayed similar symptoms would be sent to a fever clinic going through a thorough checking process, he explained.

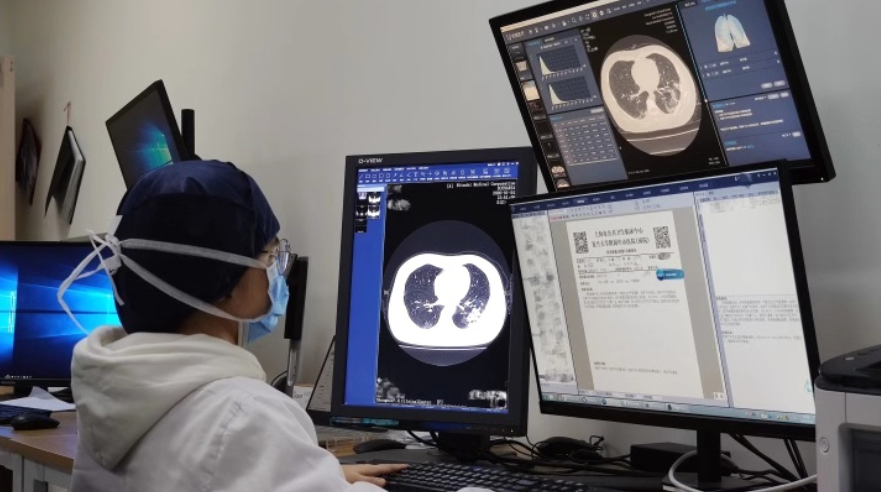

According to him, one CT scanner in these clinics could run tests on about 200 people a day. It only takes about 5 to 10 minutes for each scan, a sharp reduction in time compared to CT scans in the West that normally take one or two hours, he said.

This was thanks to a technological breakthrough made possible by Chinese AI companies.

Read more: As confirmed cases surge in Hubei, AI may have something to offer

A doctor in Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center uses an AI-powered system for diagnosis. / YITU Healthcare

A doctor in Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center uses an AI-powered system for diagnosis. / YITU Healthcare

"With mild symptoms, you go to an isolation center," Aylward told The New York Times in the interview. "They were set up in gymnasiums, stadiums — up to 1,000 beds. But if you were severe or critical, you'd go straight to hospitals. Anyone with other illnesses or over age 65 would also go straight to hospitals. The best hospitals were designated just for Covid, severe and critical."

He said that China has done an excellent job at "keeping people alive." He continued to praise the conditions of Chinese hospitals, adding that the number of ventilators in the buildings are much greater in number when compared to the Robert Koch Institute and the hospitals in Berlin.

Pictures uploaded to social media on January 25, 2020 by the Central Hospital of Wuhan show medical staff tending to patients, in Wuhan, China.

Pictures uploaded to social media on January 25, 2020 by the Central Hospital of Wuhan show medical staff tending to patients, in Wuhan, China.

When asked who would pay for the fees occurred during the whole process, "testing is free," Aylward answered. For those who have contracted the disease, if their insurances couldn't cover, "the state picked up everything."

If someone in the United States sees a doctor, the approximate cost would be about 100 U.S. dollars and if that someone winds up in the ICU, it would likely bankrupt them, Aylward noted.

Technology also played an important role in containing the epidemic, Aylward continued. "They're managing massive amounts of data, because they're trying to trace every contact of 70,000 cases. When they closed the schools, really, just the buildings closed. The schooling moved online."

As China has now resumed its economic activities, The New York Times expressed concern over the recurrence of the outbreak. Aylward responded by saying it's only a "phased restart," with different levels of resumption taking place in different provinces. Some schools are kept closed for a longer period and some "factories that make things crucial to the supply chain" are allowed to open, he added. Self-quarantine is still a must for those who have traveled and "temperature is monitored, sometimes by phone, sometimes by physical check."

Aylward also responded to western journalists saying that China's measures would be impossible to take in their countries. "There has to be a shift in mind-set to rapid response thinking. Are you just going to throw up your hands? There's a real moral hazard in that, a judgment call on what you think of your vulnerable populations," He said. "Ask yourself: Can you do the easy stuff? Can you isolate 100 patients? Can you trace 1,000 contacts? If you don't, this will roar through a community."

"I talked to lots of people outside the system — in hotels, on trains, in the streets at night. They're mobilized, like in a war, and it's fear of the virus that was driving them. They really saw themselves as on the front lines of protecting the rest of China. And the world," he said.

(Cover image: Bruce Aylward, an epidemiologist who led an advance team from the World Health Organization (WHO), speaks during a press conference of the China-WHO joint expert team in Beijing, capital of China, Feb. 24, 2020. /Xinhua)