Today, the raging COVID-19 virus has reached every continent except Antarctica. A review of the past from the 6th century shows that epidemics like the Black Death, Smallpox, Spanish flu, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), and Ebola have all played an indispensable role in human evolution and civilization.

Empty shelves where toilet paper was once stocked but now sold out in Tokyo, Japan. /AFP

Empty shelves where toilet paper was once stocked but now sold out in Tokyo, Japan. /AFP

In fact, the battle between humans and viruses is more like a cat and mouse game: You might never catch the enemy, be unsure how long the disease will last and have no idea about whether the virus will come back again.

However, no matter how cunning viruses are after experiencing variations and different hosts, humans are able to find ways to coexist alongside them, and even wipe them out following the rise of sanitary awareness and science and technology development.

The first plague in recorded history is the Plague of Justinian, which started in the 6th century in Constantinople and recurred for the next two centuries across Europe, Asia and North Africa.

The "invisible killer" accelerated the fall of Roman Empire, in which it is estimated that nearly half of the European population was killed during this time.

The Plague of Justinian was carried by infected rats on merchant ships from Egypt and Asia and there were no effective medicines to cure it. /VCG

The Plague of Justinian was carried by infected rats on merchant ships from Egypt and Asia and there were no effective medicines to cure it. /VCG

According to contemporary research, the disease was carried by infected rats on merchant ships from Egypt and Asia and there were no effective medicines to cure it. Doctors at the time tried methods such as using vinegar or telling patients to put flowers around them.

Christian followers believed that it was God that was punishing them and began performing exorcisms on the infected.

This plague put the Roman empire in trouble financially and militarily, undermining its ability to battle against the Goths and Vandals, which then impeded the unification of the Eastern and Western Empires. Modern historians think the deadly plague kept the Roman empire from achieving greater glory.

Arguably the deadliest plague in the recorded history is the Black Death.

From 1347 to 1353, it devastated late medieval and early modern Europe, Northwest Asia and North Africa. By the middle of the 14th century, Europe had lost more than 100 million people to the disease.

This long cone mask is one of the most recognizable symbols of the Black Death. Doctors wore a beak mask filled with herbs and spices to fight off the virus, along with gloves, boots and hats to avoid contracting the disease. /VCG

This long cone mask is one of the most recognizable symbols of the Black Death. Doctors wore a beak mask filled with herbs and spices to fight off the virus, along with gloves, boots and hats to avoid contracting the disease. /VCG

The word "quarantine" derives from Italy in the 15th century when the Black Death raged through the whole of Europe as well as Asia.

Venice, one of the biggest trade centers, was vulnerable to the plague. To prevent the potential carriers arriving on ships, the Venetian authorities established what is believed to be the first quarantine hospital on an island in the Venetian Lagoon which was "so big that from afar it resembles a castle," according to an observer.

The second quarantine hospital was built on another island, largely for sailors and merchants suspected to have had contact with the virus but not sick yet.

However, given the primitive state of medical conditions, the quarantine methods at that time could not effectively prevent the epidemic spreading. Without effective cures or a preventive approach, the mysterious disease fueled class hatred and "the victimization of the poor and vulnerable."

The outbreak was blamed onto some Jewish people. They suffered less severely partly because they regularly ritually washed and bathed, and their hygiene were slightly better than their Christian neighbors.

Despite the limitations of medical science at the time, the Black Death led to some notable changes like anatomical investigation and the systematic tracking of public health.

Plague in Northeast China, 1910-11

In the winter of 1910, a gruesome pneumonic plague stretched across the northeast region of China (known as "Manchuria"). It has been termed the worst outbreak in the 20th century as it claimed over 60,000 deaths within four months. The first fatality was reported in Manzhouli, one of China's northern border cities with Russia, and the disease swiftly spread to Harbin, capital of China's northernmost province of Heilongjiang, via railways, causing enormous damage to the economy and severe social chaos.

According to a report from the International Plague Conference held at Mukden (currently Shenyang, China's northeast Liaoning province) in April 1911, highly mobile occupations including hard laborers from Shandong province, businessmen and refugees accounted for nearly 64 percent of plague patients in Northeast China during 1910-1911. The modern medical profession agrees that the movement of large numbers of migrant workers from plague-affected areas returning home for Chinese Lunar New Year was a key factor in the plague's spread.

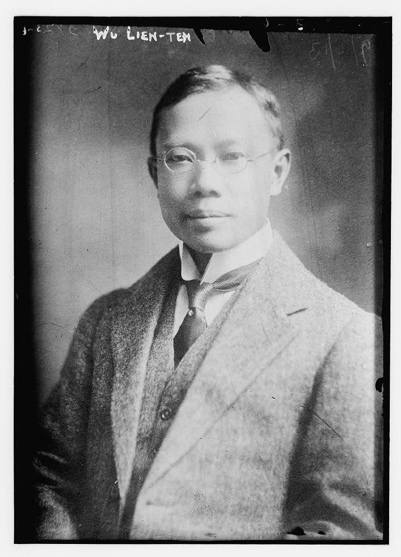

Plague fighter: Dr. Wu Lien-Teh

Facing intrusive threats from Russia and Japan on the pretext of epidemic prevention and pressures from foreign diplomatic corps, the government of Qing Dynasty (1636-1912) assigned Cambridge-trained young Chinese doctor Wu Lien-Teh to end the disaster. He is regarded as the founder of Chinese public health service and system. His arrival also heralded a "sanitary awakening" in China as many western medical methods were adopted to control pandemics.

Dr. Wu Lien-Teh (1879-1960), a Malaysia-born Chinese doctor known for fighting the plague in northeast China in 1910-1911. /Photo via Weibo

Dr. Wu Lien-Teh (1879-1960), a Malaysia-born Chinese doctor known for fighting the plague in northeast China in 1910-1911. /Photo via Weibo

Dr. Wu performed the first-ever postmortem exam in China. He discovered Yersinia Pestis in body tissue and further confirmed that the epidemic was pneumonic plague, which could be transmitted by human breath or sputum. This was contrary to the general idea that plague could only be transmitted by rats or fleas and could not be transmitted from person to person.

Plague patients are quarantined in train containers in northeast China, 1910. /VCG

Plague patients are quarantined in train containers in northeast China, 1910. /VCG

A series of preventive measures to contain the outbreak were implemented under his instruction when antibiotics were not available at the time, including setting up quarantine units, imposing travel bans, ordering blockades to stop infected persons from traveling and spreading the disease.

In this public health crisis, Wu not only designed and invented the first Chinese sanitary gauze-and-cotton mask to help people reduce droplet transmission, but also sent a petition to the Emperor for cremation of the deceased though which was seen as an act of desecration in feudal era. Eventually, the mortality figures started to decline and the rampant plague ran its course.

Dr. Wu designed the first Chinese sanitary gauze-and-cotton mask to help people reduce their chances of being infected. /Photo via Weibo

Dr. Wu designed the first Chinese sanitary gauze-and-cotton mask to help people reduce their chances of being infected. /Photo via Weibo

A month later, he chaired the first International Plague Conference in Shenyang which was attended by scientists from 11 countries including Britain, China, France, Germany, the United States. In 1935, Dr. Wu was nominated for the Nobel Prize due to his great efforts in battling the disease.

The Harbin plague was the first instance of modern medical techniques being applied to a public health crisis in China. Lessons of transparency and transnational cooperation from that event more than a century ago are still relevant to China and the world today as countries struggle to deal with the novel coronavirus.