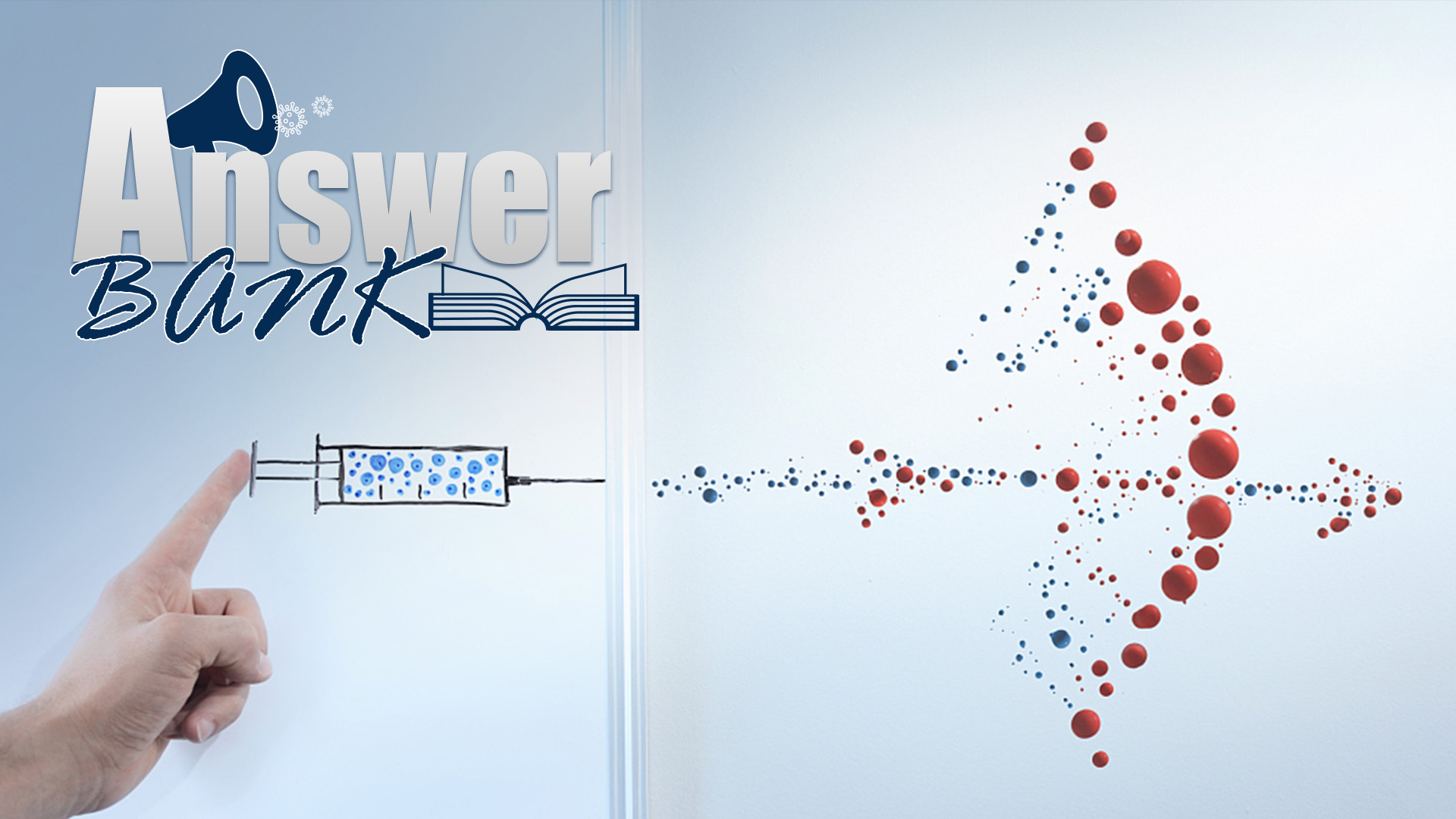

Herd immunity, also known as community immunity, occurs when a sufficient portion of a population is immune to a specific disease (usually through vaccination and/or prior illness), so that it can make the spread from person to person unlikely. 1

According to this theory, the greater the proportion of a population that is immune or less susceptible to a disease, the lower the probability that a susceptible person will come in contact with an infected person.

If a sufficient number of people (or a herd) are immune, the infection will no longer circulate, thereby protecting individuals who have not developed immunity.

The medical term – herd immunity – suddenly became a buzzword after Boris Johnson set it as part of the UK strategy in fighting the new coronavirus.

"Our aim is to try and reduce the peak [of the infections, broaden the peak, not suppress it completely," Patrick Vallance, chief scientific adviser to the UK government, told BBC on Friday.

"Also, because the vast majority of people get a mild illness, to build up some kind of herd immunity so more people are immune to this disease and we reduce the transmission."

Top Chinese epidemiologist Zhong Nanshan, who has been at the forefront of the fight against COVID-19 in China, talked about the benefit of building up immunity, saying that people who are infected with the disease would develop an antibody after recovery, making it less likely for them to get infected again.

But for people to enjoy herd immunity, about 60 percent of the population would need to contract the virus, said the UK government.

Opinions vary on the "herd immunity" strategy carried out by the UK government. Here we sorted out some expert comments about herd immunity on Science Media Center.

Prof Martin Hibberd, professor of Emerging Infectious Disease, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine:

The government plan assumes that herd immunity will eventually happen, and from my reading hopes that this occurs before the winter season when the disease might be expected to become more prevalent.

However, I do worry that making plans that assume such a large proportion of the population will become infected (and hopefully recovered and immune) may not be the very best that we can do. Another strategy might be to try to contain longer and perhaps long enough for a therapy to emerge that might allow some kind of treatment.

Prof Matthew Baylis, Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecological Sciences, University of Liverpool:

Estimate predicts about 60% percent of the population would need to contract the virus to get herd immunity. And this is deeply concerning – taking the low fatality rate estimate of one percent, even 50 percent of the UK population infected by COVID-19 is an unthinkable level of mortality.

But it doesn't have to be – and it won't be – this way. By reducing the number of people that one person infects, on average, then we lower the point at which herd immunity kicks in.

From an epidemiological point of view, the trick is to reduce the number of people we are in contact with (by staying more at home), and reduce the chance of transmission to those we are in contact with (by frequent hand washing) so that we can drive down the number of contacts we infect, and herd immunity starts earlier.

Professor Peter Openshaw, former president of the British Society for Immunology and professor of Experimental Medicine at Imperial College London:

SARS-CoV-2 is a novel virus in humans and there is still much that we need to learn about how it affects the human immune system. Because it is so new, we do not yet know how long any protection generated through infection will last.

With the novel SARS-CoV-2, the situation may be very different but we urgently need more research looking at the immune responses of people who have recovered from infection to be sure.

Dr Erica Bickerton, the Pirbright Institute:

Immunity to SARS-CoV-2 is not yet well understood and we do not know how protective the antibody response to this new virus will be in the long-term.

This is a new coronavirus and there is a lot of work going on to understand immunity to this virus. It is too early to say how long immunity lasts or how the virus will adapt to escape immunity. There is still much to be learned.

Anthony Costello, former World Health Organization director:

The UK government was out of kilter with other countries in looking to herd immunity as the answer. It could conflict with WHO policy.

Does coronavirus cause strong herd immunity or is it like flu where new strains emerge each year needing repeat vaccines? We have much to learn about Co-V immune responses.

(1: Why is herd immunity so important? H. Cody Meissner AAP News May 2015, 36 (5) 14; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/aapnews.2015365-14)