Non-essential staff at the UN headquarters began working from home earlier this week. Tech giants and small companies have also put in place remote work policies as the U.S. states of California and Illinois issue stay-at-home orders due to the coronavirus pandemic. Italy, France, Canada and numerous countries plagued by the outbreak are also joining life under lockdown in an unprecedented "working from home" movement that is changing the landscape.

A little history

Starting from the 1760s, machines such as the Spinning Jenny, the steam engine, and the power loom created factories and workshops that led to people working at designated spaces. "Office working" eventually became the norm, which was further reinforced with the introduction of a five-day, 40-hour workweek in 1926 and the invention of cubicles in 1968.

It wasn't until the 1970s when the clean air movement prompted people to reduce their commute time, that the modern concept of "working from home" really took off. Jack Nilles – an engineer who played a leading role in designing certain space vehicles and communication systems – coined in 1973 the term "telecommuting" in his book Telecommunications-Transportation Tradeoff: Options for Tomorrow. The teleworking tide became popular with the advent of the first personal computers and the oil crisis that triggered embargoes in the following years.

With the invention of the internet and Wi-Fi, the "remote working" trend was widely embraced by big tech companies such as IBM and AT&T. Such a model seems unequivocally modern: living a low-carbon life, forgoing office rentals, and creating flexibility for working parents.

The subsequent 2008 global financial crisis led to a large-scale downsizing of workers while encouraging more companies to adopt the "remote working" model in order to save costs on leasing office space. Hashtags like #DigitalNomad and #WorkFromAnywhere on social media led more to join the army of remote workers. Globally wise, by 2018, over 50 percent of employees worked from home at least half of the week, according to a study by the world's largest office-space provider IWG. From 2005 until now, the number of regular remote workers rose globally by 140 percent. A 2019 report by freelance platform Upwork predicted that 73 percent of employers around the world will have some remote employees by 2028.

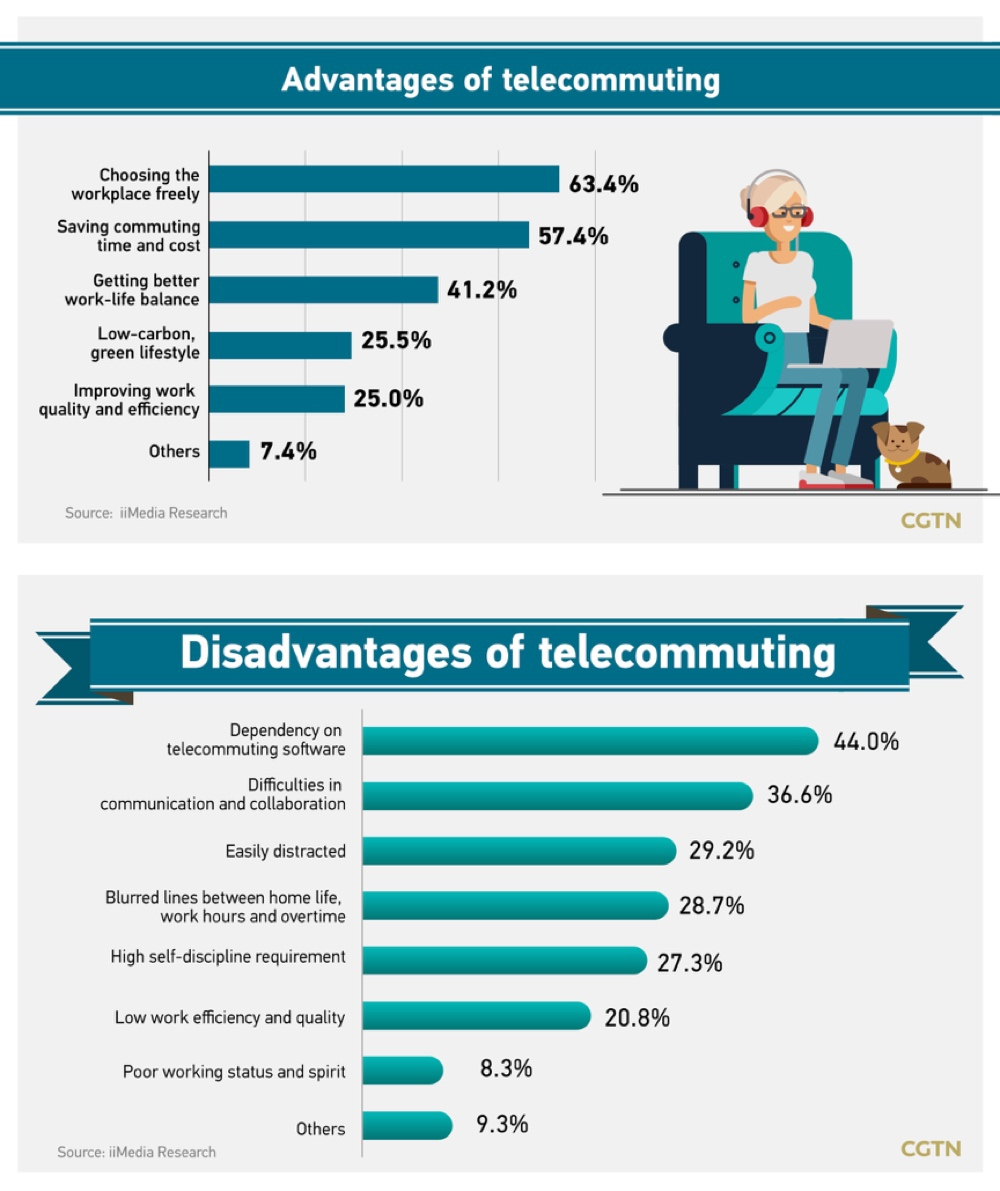

However, IBM gave up this model – with which it had begun experimenting in as early as 1979 – in 2017 after revenues plunged for 20 consecutive months. That may illustrate the disadvantages of working from home: easy distractions, communication difficulties and unreliable internet connections. "Work at home if you can, but don't expect it to be paradise," that was a headline from Financial Times last month.

'Working from home' under coronavirus

While the argument over the pros and cons of working from home has continued for over a decade, the coronavirus outbreak which has now spread to over 150 countries has unexpectedly served as a boon to this trend.

In China, where confirmed cases of coronavirus were first reported, working from home has gained traction after epidemiologist Zhong Nanshan said the virus can spread via human-to-human transmission. Some 200 million Chinese have been working in pajamas and casual wear since the extended Spring Festival holiday ended in early February.

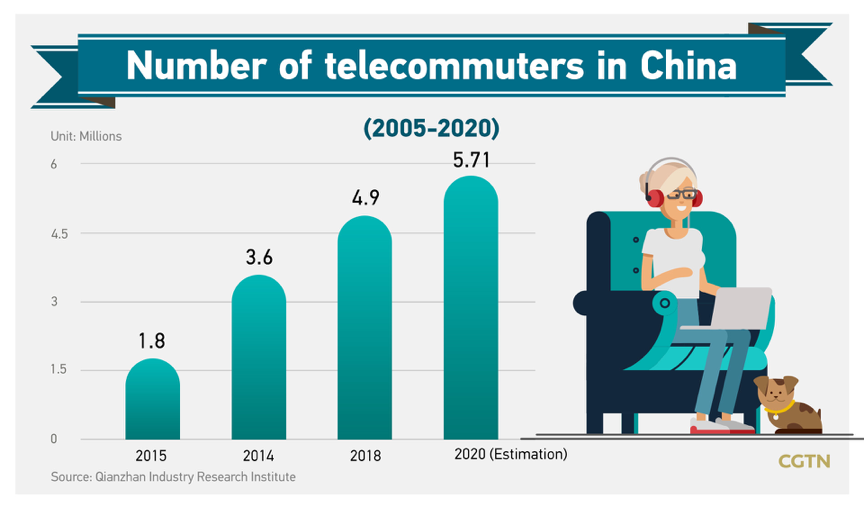

Like in the West, working from home is not a new concept in China, especially with the rapid development of teleconference and video chat apps over the years. Since 2015, the number of telecommuters in China has risen by 217 percent from 1.8 million to an estimated 5.71 million, according to industry research firm Qianzhan.

The last time people worked at home on a comparable scale was during SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak 17 years ago. That was when Alibaba asked all its employees to work from home and when it gave birth to its Taobao consumer-facing website, which went on to become one of the largest such platforms in the world. Other nascent internet startups like retailer JD.com and online travel agency Trip.com (previously Ctrip) have also been implementing remote working policies to tide over the tough times. Since then, more digital firms have followed suit.

But for a number of Chinese who are used to being corralled in drab cubicles over the eight-hour weekday model or even the hustle of the "996" schedule, working from home is a whole new experience.

"It's difficult for me to concentrate when I'm working from home, because I'm easily distracted by the temptations of snacks and my bed," Ivy Qian, who worked remotely for nearly a month, told CGTN.

Though the outbreak gave her the first chance to work at home in her six-year career as an online course editor, she's waiting anxiously to go back to her office because that would provide better work/life balance.

Workers are seen in an office tower in the Canary Wharf financial district at dusk in London, Britain, November 17, 2017. /Reuters

Workers are seen in an office tower in the Canary Wharf financial district at dusk in London, Britain, November 17, 2017. /Reuters

For, Liz, a business analyst from a tech company based in California's San Jose, it's another story. The outbreak didn't change her work much since she works remotely. She and her colleagues, who are in different time zones, would arrange meetings accordingly.

Liz enjoys the flexible work culture but she noted that working from home requires high self-discipline and having the boss see what she has done.

The overwhelmingly traditional education sector has been one of the most affected during the outbreak. As more classes are being delivered online, teachers and students in primary and secondary schools are experiencing tremendous disruption.

English teacher Guo Xiaolin agrees that it is less effective when she teaches her students through the screen, as she can't get instant feedback from the students and they aren't as concentrated as they are in the classroom. But Guo said the online courses can enable students from rural areas to get access to high-quality educational resources.

As the coronavirus tapers off in China, more and more Chinese are going back to the office. Qian said working is an important way to interact with society and that people shouldn't always be alone. "Talking or collaborating with others face to face is important to me.”

But "the current situation should fundamentally change things in the future," said John, a Beijing-based journalist, who's been at home about half of every week. For him, working at home is "generally more productive and peaceful." Disadvantages? "I tend to end up with one cat on my lap and another trying to sleep on the keyboard."

In his hometown back in London, remote working wasn't prevalent before the coronavirus. With confirmed cases appearing in the UK, many people have been working one week on, one week off from home for the last few weeks, he said. "But they will now be working from home full time for the foreseeable future."