The UK response to the COVID-19 pandemic has been met with a mix of curiosity and anger from experts at home and overseas, with accusations of passivity in Chinese media as recently as last Sunday, but over the past seven days the approach has rapidly accelerated from suggestions to orders and herds to isolation.

That journey, still slower and more incremental than in countries like Spain, Italy and France, will reshape life in Britain for years to come.

While there isn't a one-size fits all response — the UK does not have an epicenter, unlike China or Italy, which poses different challenges — the evidence from Asia has been that moving early and hard while testing extensively, isolating and tracing contacts of infected people is effective in slowing the spread of the virus.

Britain's Prime Minister Boris Johnson gestures during a COVID-19 press conference, Downing Street, London, March 20, 2020. /AP

Britain's Prime Minister Boris Johnson gestures during a COVID-19 press conference, Downing Street, London, March 20, 2020. /AP

Yet the UK, along with the U.S. at federal level and countries including Switzerland, has opted for a phased approach, albeit now at a faster pace, designed to strike a balance between safeguarding the economy and civil liberties on one side and protecting public health on the other.

"Our aim is to try and reduce the peak, broaden the peak, not suppress it completely," Sir Patrick Vallance, England's chief scientific adviser, told the BBC on March 13.

"Because the vast majority of people get a mild illness, to build up some kind of herd immunity so more people are immune to this disease and we reduce the transmission, at the same time we protect those who are most vulnerable to it. Those are the key things we need to do."

A tourist ticket booth in a normally bustling part of central London is closed, March 22, 2020. /AP

A tourist ticket booth in a normally bustling part of central London is closed, March 22, 2020. /AP

The dramatic strategy shift in the past week — and the publication of detailed analysis of the impact of policies — came after a government-commissioned report from the COVID-19 team at Imperial College London was released on Monday.

It indicated the plan followed by Boris Johnson's government, which drew headlines for incorporating herd immunity and relying on behavioral science to "nudge" the public to social distance and take precautions, could have drastic results.

The Imperial team projected that a mitigation strategy — slowing but not necessarily stopping the epidemic, while protecting the most at-risk people — could lead to 250,000 deaths in the UK, with demand for intensive care beds eight times greater than availability.

"I can't help but feel angry that it has taken almost two months for politicians and even 'experts' to understand the scale of the danger," Richard Horton, editor-in-chief of The Lancet, which published its first paper on the virus in January, tweeted on Tuesday.

The use of nudge theory, changing behavior through coaxing or encouraging alternative options, has been applied to British public policy since 2010 when the coalition led by David Cameron set up the so-called "nudge unit," which has since become The Behavioural Insights Team, a private enterprise advising governments and businesses around the world.

"Creating substitute behaviors and new barrier-forming habits are the most effective way of curbing face touching," a blog on the company's site advised on March 5. "We need to work out the most promising approaches and the best way of communicating them – fast."

While encouraging rather than enforcing changes of behavior was an attractive option for Johnson, a prime minister with libertarian instincts who has repeatedly railed against nanny statism, the escalation in known cases — over 5,000 with 233 death as of Saturday — together with evidence the warnings were not being taken seriously by all, indicated it needed to be complemented by more dramatic action.

Johnson ordered public venues to close on Friday, alongside a huge financial package designed to help workers and businesses, though minutes after calling on the UK "as far as possible to stay at home" undermined the urgency of the message by saying he "hoped to see" his own mother on Mothering Sunday, counter to government advice.

By Saturday, the prime minister was back on message telling reporters that the "single best present that we can give is to spare them the risk of catching a dangerous disease."

He warned that the National Health Service (NHS) could be "overwhelmed" if people did not follow government advice on social distancing and on Sunday it was confirmed that 1.5 million people in at-risk categories will be told to stay at home for 12 weeks.

The shift to a suppression approach – reducing reproduction (the average number of secondary cases each case generates) to below one by breaking chains of transmission and maintaining the situation indefinitely — could still lead to "a few thousands or tens of thousands" of deaths, according to the Imperial team's modeling.

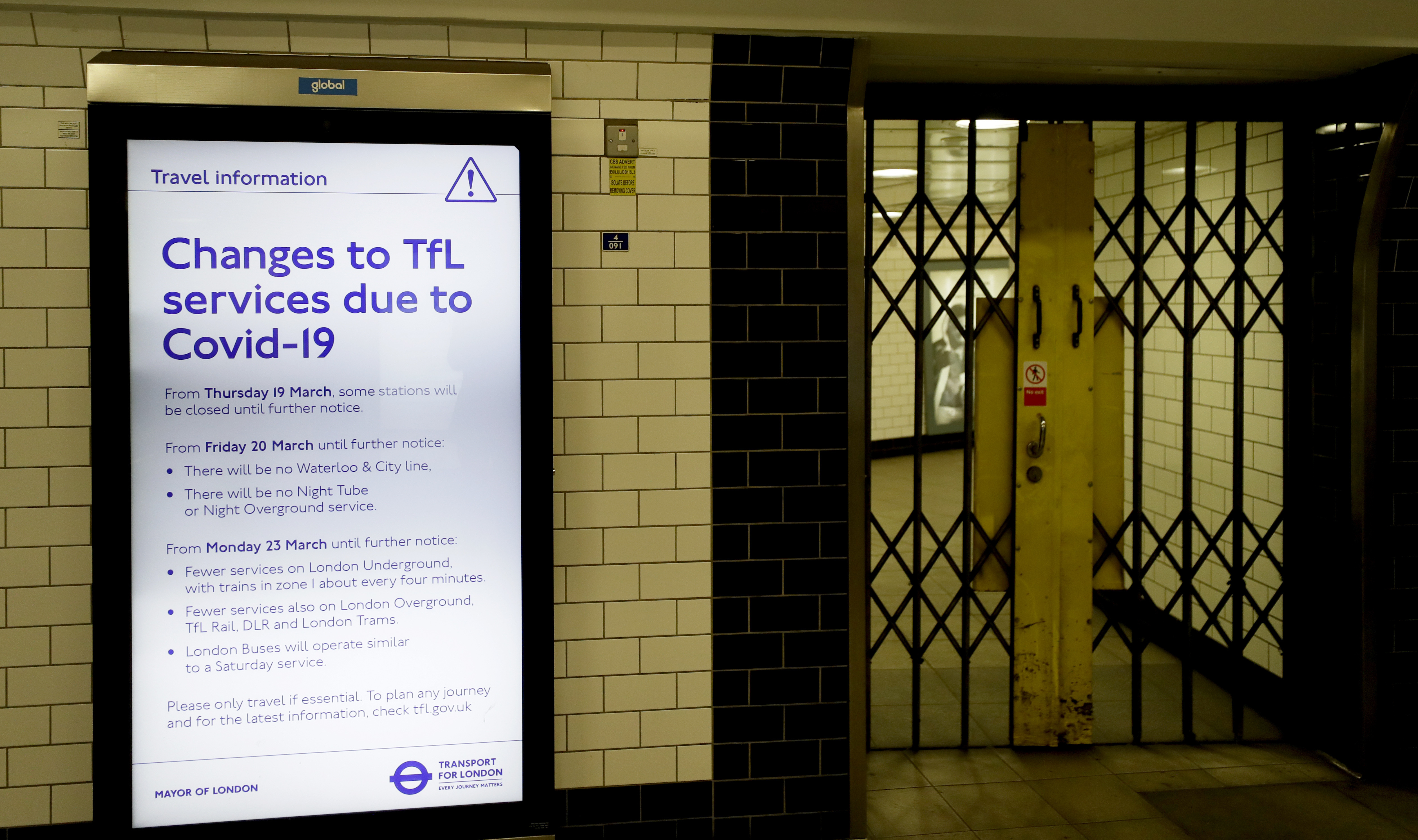

An information sign warns of changes to public transport services because of the COVID-19 outbreak, London, March 21, 2020. /AP

An information sign warns of changes to public transport services because of the COVID-19 outbreak, London, March 21, 2020. /AP

Johnson on Thursday said he hoped Britain will "turn the tide in 12 weeks," though the Imperial report suggested suppression measures would have to be kept in place until a vaccine is available.

"Bit by bit, day by day, we are all helping to delay the spread of the disease, and to give our amazing NHS staff time to prepare for the peak," the prime minister said in a statement released on Sunday. But that seems likely to also involve further restrictions, and there is space for further suppression measures.

Public transport is operating on a reduced service, but traveling around the country by train is still possible. Home working has dramatically increased, but isn't compulsory for all those who can work remotely.

The environment secretary on Saturday refused to rule out food rationing, and while some non-essential shops, like department store John Lewis, are choosing to close though there has not been an order to do so.

And while schools are largely closed and bans on public gatherings are now in place, a plan for enforcement is less clear.

In France, anyone who contravenes the much tougher measures — people are only allowed to leave home for essentials like food or medicine or if they cannot work from home — can be fined and 100,000 police have been deployed to enforce the new rules.

In all likelihood, the UK's rapid shift in strategy will have several more phases — and looking at evidence from other countries, more restrictions in the days and weeks ahead seem inevitable.