Editor's note: Chris Hawke is a graduate of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism and a journalist who has reported for over two decades from Beijing, New York, the United Nations, Tokyo, Bangkok, Islamabad and Kabul for AP, UPI and CBS. The article reflects the author's opinions, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

Voices on the American right are using the COVID-19 epidemic to renew their calls for decoupling the U.S. economy from China.

In a widely discussed article in The American Interest, Andrew Michta states, "The subsequent era will, I hope, be one of strategic reconsolidation, with a special focus on onshoring critical supply chains that have been moved to China." He adds, "If, once this crisis is over, we do not have at least a blueprint for rebuilding America's manufacturing base and restoring our ability to provide critical supplies to the country regardless of the actions of our adversary, a decisive opportunity will have been squandered."

Michta cites the spread of the virus, and mistakes made early in the battle against it, as a reason to isolate and shun China.

However, as the virus spreads throughout the world, this line of argument is being heard less and less, and with good reason. Nearly every country has made mistakes in its initial response to the outbreak. This pointedly includes the U.S. fighting COVID-19 turns out to be difficult. With the benefit of hindsight, China's response looks very effective overall.

Michta goes on to say decoupling must occur because offshoring manufacturing to China has made supply chains vulnerable. But supply chains are vulnerable exactly because forces favoring decoupling in the U.S. started a trade war, a move which has unraveled ties between the two nations rapidly. The racism, xenophobia, and lack of empathy or support flowing from Washington during the outbreak in Wuhan exacerbated this.

Mitcha says manufacturing jobs have moved to China and devastated communities that relied on factory jobs.

Some jobs have indeed been lost to China. However, U.S. studies repeatedly show that jobs lost to robots and automation greatly outnumber those lost to globalization. President Trump's pledge to create jobs by bringing manufacturing back to the United States has not borne fruit. Even if Trump succeeds, factories do not need as many people as before, and the new jobs will go to highly trained workers.

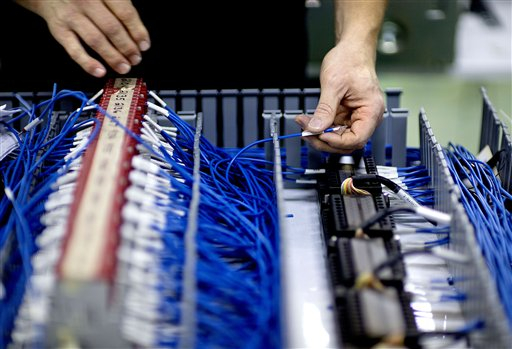

A worker wires circuits for a control panel at Factory Automation Systems at the company's Atlanta facility, U.S., January 15, 2013. /AP

A worker wires circuits for a control panel at Factory Automation Systems at the company's Atlanta facility, U.S., January 15, 2013. /AP

Blue-collar jobs as they existed in the 1960s and 70s are history, along with work for scribes, wheelwrights, and fax machine repairers from other bygone eras.

Michta also attributes the rise of populist governments in the West to dislocations caused by jobs moving to China.

The pain being felt by swaths of non-college educated workers is real, but it is not caused by China. In recent years, there were plenty of jobs in the U.S. Even so, increases in the costs of education, health care, child care, and real estate compared to wages have left many families living paycheck to paycheck, even as profits flow to the richest among us.

Globalization has created tremendous wealth. In the U.S. and other countries, those who control tax laws, labor laws, and the medical system are choosing to direct this money into their own pockets. This is a problem of policymaking and labor and tax laws, not foreign trade.

For proof of this, look to Northern Europe or north of the U.S. border at countries that have made different policy decisions.

As the virus spreads, walls are springing up around the world. When the current crisis ebbs, these barriers are at risk of remaining. But retreating to within our national borders would be a crucial mistake.

The many global problems we face require global solutions.

For the COVID-19 epidemic, for example, countries with excess capacity of medical care providers and medical supplies could help other areas that are being overwhelmed. Countries could work together to share information about how the disease spreads and how to treat it. China has done both these things.

Countries with extra hospital beds could offer them to nations that are overwhelmed, as Germany has recently done.

If we don't start working together globally, problems like a poisoned environment, extreme weather, food shortages, and mass dislocations will start touching all of our lives in ways just as menacing as the current epidemic.

Building walls and blaming other people are not the solution. Coming together is the only way forward.

The current coronavirus epidemic has a specific, cruel example of the cost of decoupling.

The U.S. and China had been close collaborators in public health for over 30 years.

An article in The Atlantic by Peter Beinart details the close and effective health care cooperation between the U.S. and China amid the 2002 SARS outbreak, the 2009 swine flu outbreak in the U.S., and their joint work on the Ebola outbreak in West Africa from 2014 to 2016.

But last summer, as Trump pushed his trade war with China and flirted with the concept of decoupling the nations' economies, the U.S. told its embed at the Chinese CDC, epidemiologist Linda Quick, to go home. Her job would have been to convey to the U.S. government the urgency of the epidemic. This may have or may not have sped up the Trump administration's lethargic response to the threat, but it shows we have much more to gain by cooperation than by decoupling from each other.

Social distancing is great for preventing epidemics, but terrible for solving world problems.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)