Editor's note: COVID-19 Economic Analysis is a series of articles offering expert views on developing micro and macroeconomic situations around the globe amid the coronavirus pandemic. This article's author Jimmy Zhu is a chief strategist at Singapore-based Fullerton Research.

Global central banks led by the U.S. Federal Reserve have unveiled unprecedented monetary stimulus in the past month to arrest the rising economic uncertainties and financial market volatility. Still, there is no visible recovery in the stock market, as growing concerns on the effectiveness of these measures weigh on market sentiment.

On March 3, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) decided to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 50 bps, as the Fed judged that coronavirus poses evolving risks to economic activity. This was the first emergency rate cut since October 2008, when the global financial crisis kicked off. In less than two weeks, the FOMC decided to slash the target range for the federal funds rate to 0 to 1/4 percent.

The relaunch of the emergency rate cut also signaled that the powerhouse was going to enter into crisis management mode, which is still highly controversial. The purpose of cutting interest rates always aims to reduce corporate borrowing costs and boost consumption. This kind of monetary action may not work well in the background of the global pandemic, even with some negative impacts.

When the spread of the coronavirus accelerates, economic activities and social communications are not supposed to accelerate in order to quickly contain the spreading.

Furthermore, aggressive rate cuts at this stage may have significant side effects. First, with major central banks' policy rates already close to zero, they are running out of the further policy room if economic conditions further deteriorate or any unexpected event occurs. Investors are well aware of that, and that's one of the reasons behind the huge selling off in March.

Second, most of the businesses are not looking to expand and most individuals have stopped investing. Companies are not likely to invest for the time being just because of lower borrowing costs. Thus, cutting the interest rates to near-zero at this moment only erodes the savers' interest at this stage when "cash is the king."

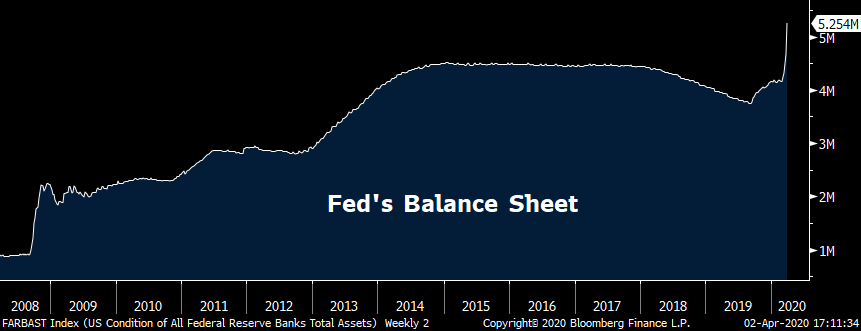

Third, how to smoothly withdraw such a mega-sized stimulus will be the next challenge for central banks. Recall those days of 2003-2005 when former Fed chair Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen took a long time to smooth the volatility after they started hinting that they were going to raise the rates and taper the balance sheet.

The Fed is not likely to keep its balance sheet at the current level for a long period once the virus spreading eases. Current Fed chair Powell is expected to find it tough to explain to Wall Street that its plan to reduce the balance sheet without spooking the financial market.

The policy tools that are left for the Fed

The Fed is not likely to adopt the negative policy rates as such moves would pressure the U.S. 10-year government bond yield into negative territory. As U.S. Treasuries are considered as one of the safest assets in the world and many other central banks are holding them as foreign reserves, negative yield may cause the Fed to face increasing pressure from its foreign counterparts.

We expect the Fed's upcoming policy may shift into "yield curve management." As the economic outlook remains challenging, the long-tenor Treasures yield may continue to drop, while the short-term rates have limited downside room. This may cause a consistent inversion in the yield curve, a sign that the economy is going to enter a recession.

Over the last month, the Fed has injected over one trillion U.S. dollars cash through daily overnight repo operations, with a much higher amount than the QE program. The U.S. three-month and 10-year yield spread has widened to 50 bps from below zero a month ago.

What the Fed can do is to continue to appoint its New York desk to inject liquidity into the market to pressure the short-end rates to move lower, and there is a need to do that because dollar liquidity remains a concern.

As of April 2, the U.S. has reported over 210,000 people who have been infected by the virus, with cases accelerating daily. If the country can't reverse the current situation, the existing over two-trillion-U.S.-dollar emergency package will dry up very soon.

As a result, the U.S. government will have to seek additional cash to bail out the economy, and that will require the Fed to continue to inject cash into the financial system, otherwise the short-term rates may spike due to overwhelming cash demand.

On the other hand, the Fed is not likely to accelerate its QE to avoid the long-end yield moving lower (Note: one of the major purposes of QE is to suppress long-term borrowing costs). When the 10-year government yield is almost half percent, increasing the monetary base won't have much positive impact on the economy.

How other central banks are faring

Most of the major central banks in the advanced economies mainly followed the Fed's move last month – it slashed the rates toward zero and expanded the assets purchasing program. Among those central banks, Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) shocked most of the investors.

For the first time in its 75-year history of being responsible for monetary policy,the RBA can no longer meet its objectives using traditional monetary policy. Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) reduced its cash rate to an all-time low of 0.25 percent, and this was an unscheduled decision for the first time since 1997. The RBA said the board would not tighten policy until it achieves its employment and inflation goals.

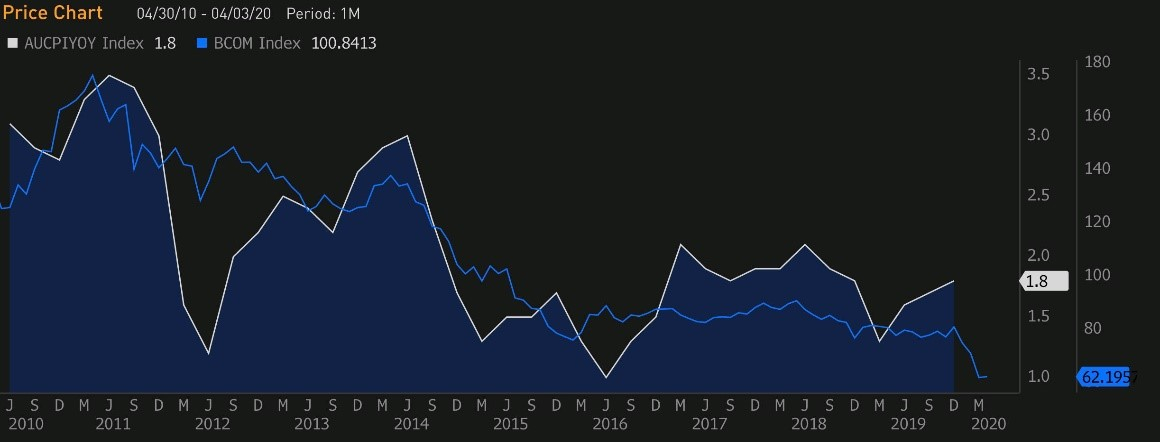

Since the early 1990, the RBA set the inflation rate target at 2-3 percent. Australia heavily relies on the commodities' exports, and its inflation growth has been staying around its lower bound of the target range over the past five years, largely due to the global economy slowing down.

The chart below shows global commodity prices have a substantial impact on the Australia inflation rate. Australia CPI grew 1.8 percent in December last year, while the Bloomberg commodity index was around 80 in that period. However, the commodity index has dropped over 20 percent since then as massive factories around the world were shut down, which highlights the severe deflation risk in the country.

Australia CPI YoY (white line), Bloomberg Commodity index (blue line). /Bloomberg

Australia CPI YoY (white line), Bloomberg Commodity index (blue line). /Bloomberg

Taking note that Australian policy rate used to be much higher than those developed economies, its sudden decision to adopt the zero-interest rate policy reflects the RBA's extreme bearish outlook on the global economy. It remains unclear when the coronavirus spread will start slowing down, but the negative impact on the global growth activities will likely continue throughout 2020 at least.

Under such circumstance, the RBA is expected to keep the policy rates at current level toward the end of the 2020. If the global activities are to further slow, the Australian central bank may further expand its bond buying program, a move to create more money in the financial system when policy rates have little room to boost the lending. RBA said on March 20 that it also purchased five billion Australian dollars local government bonds, in the first round of its unlimited quantitative easing program.

The European Central Bank (ECB) kept the policy rate unchanged in March, as its benchmark lending rate was already at zero since early 2016. Similar to the RBA, the ECB has very little room to further cut interest rates, and the only monetary stimulus left could be asset purchasing.

For the ECB, one of the key metrics it watches is also inflation rate. The ECB's inflation target is set at near two percent. The inflation growth decelerated sharply this year, slowing to 0.7 percent over year in March from 1.2 percent in February. As the euro zone economy highly depends on the manufacturing, falling energy price poses huge risk that the euro zone will enter into deflation as early as in April.

Thus, the ECB would have to further increase its bonds purchasing program, and frankly it may need to consider directly purchase those corporate bonds to bail out those troubled companies. Prolonged zero-interest rate in euro zone has been largely discouraging many commercial banks to lend to the private sectors due to lower net interest margin, a key measure of banks' profitability.

However, such direct corporate bond buying program are likely to face strong objections from some hawk members in the region, such as Germany and Netherlands. Since the euro zone debts crisis almost a decade ago, Germany has refrained from supporting big stimulus package to aid those troubled economies in eurozone economies, because the largest economy in the region has been accusing those monetary measures help little but only increasing regional financial risk and hurting German saver's interest return.

The ECB's chief Christine Lagarde has kept repeating that central bank shouldn't be the only "player" in the region, as she urged the leaders in the currency bloc to speed up the fiscal stimulus. However, there hasn't been any concrete solutions in the euro zone regarding the further fiscal measures to counter the coronavirus impact on the economy.