As the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps the world with hundreds of thousands of new infections reported every day, many have turned to the prospect of a vaccine, but how soon can we have one?

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) last month, a COVID-19 vaccine is still at least 12 to 18 months away.

Eighteen months might sound a long time for the still-escalating pandemic, but it is already considered a breakneck speed for launching a new vaccine.

Based on past experience, it usually takes eight to 20 years to develop a new vaccine.

Some epidemics ended before vaccine development was complete. For example, work on SARS vaccines was canceled after the outbreak was contained.

But the process has been greatly accelerated this time, thanks largely to Chinese scientists who successfully sequenced the genome of the novel coronavirus and shared it with the world in early January.

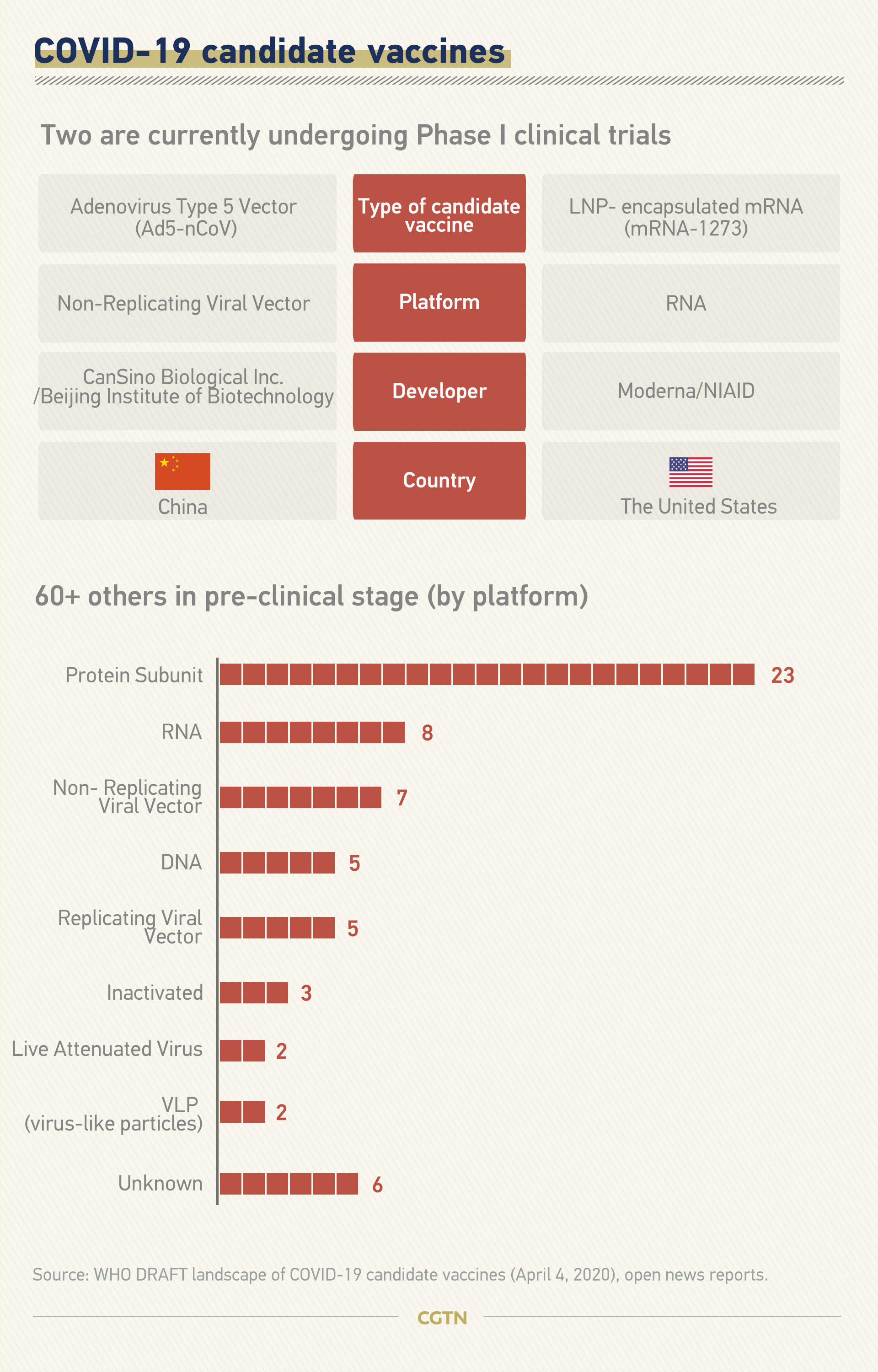

The WHO has highlighted at least 60 COVID-19 vaccine candidates, with many having started animal tests. Researchers around the world have also joined the race.

Two most advanced candidate vaccines entered clinical trials on human bodies on March 16 – fewer than four months after the disease was first reported.

Read more:

COVID-19 Global Roundup: International vaccine collaborations

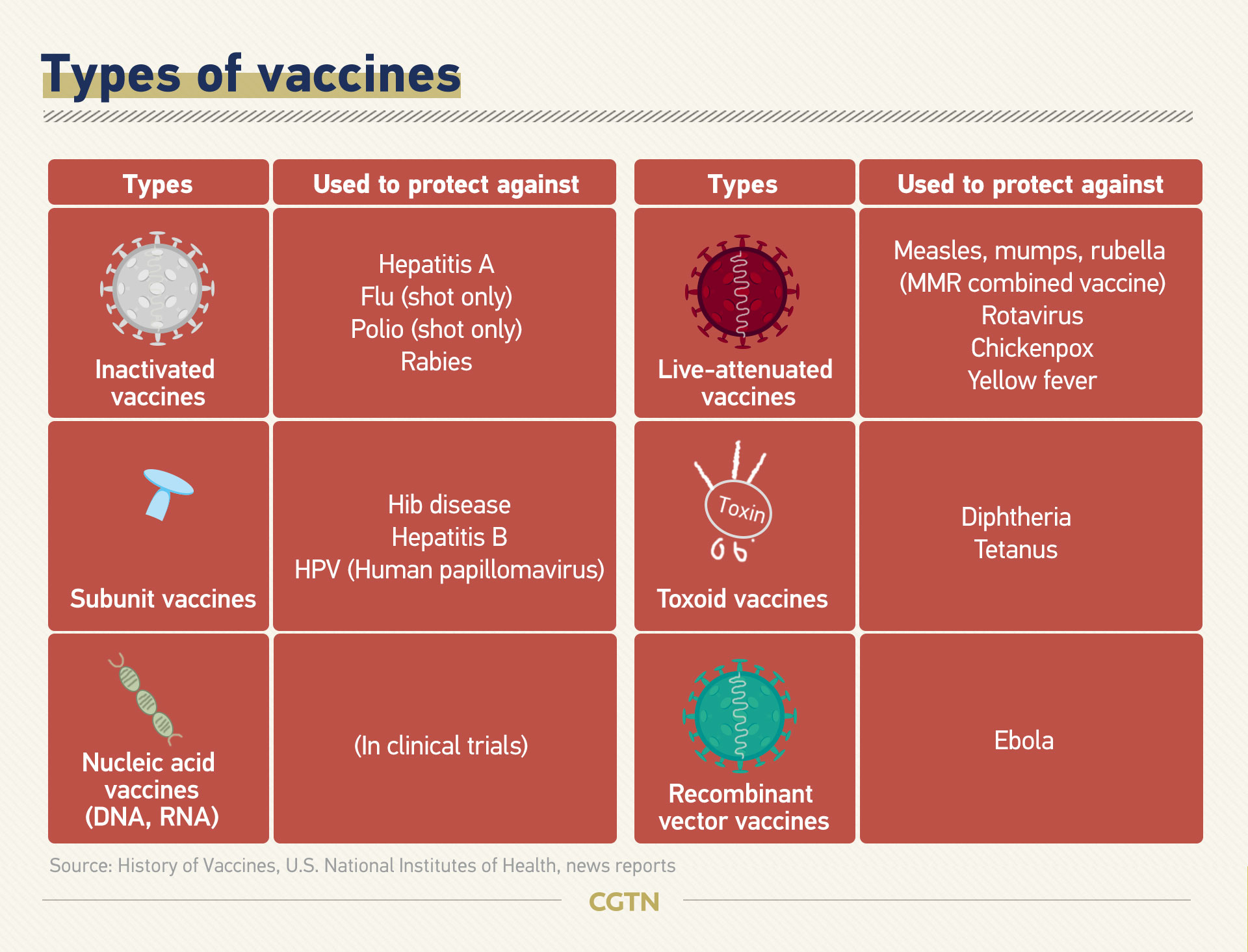

Different approaches are adopted to develop a vaccine for the novel coronavirus.

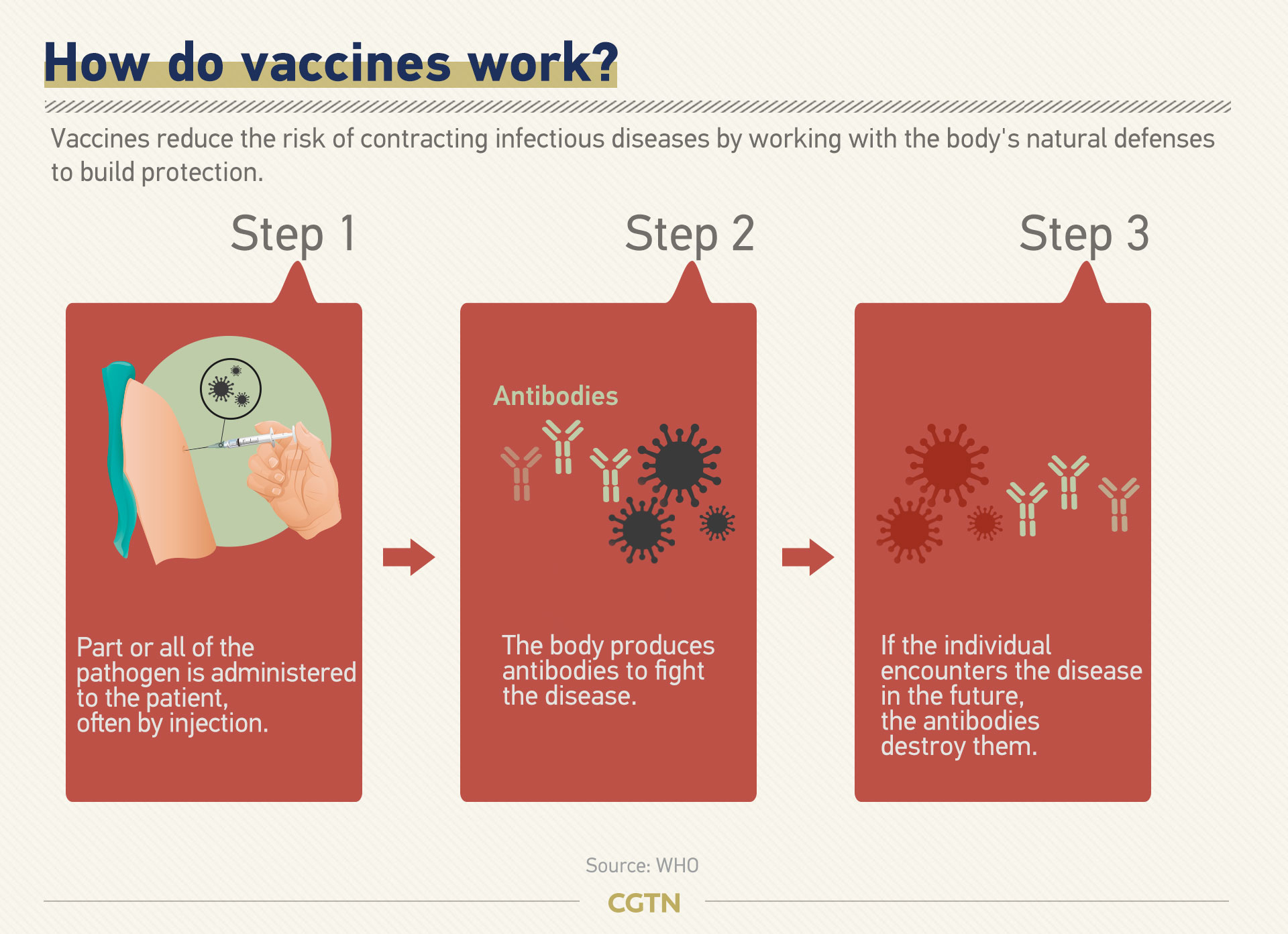

Traditionally, vaccines are made with dead or weakened forms of the pathogens so that they cannot cause diseases. They are called inactivated vaccines and live-attenuated vaccines, which elicit strong protective immune responses.

Another common type, subunit vaccines, contain selected pieces of the pathogen as antigens instead of the whole pathogen. They cause less adverse reactions than inactivated vaccines or live-attenuated vaccines, but are often less effective so they require booster shots.

All three types are under development for COVID-19 vaccines. But it is the newer approaches that are in the spotlight this time.

Among the two vaccines that entered Phase I clinical trials, one is in China with a recombinant adenovirus vector-based vaccine (Ad5-nCoV), while the other is an mRNA vaccine (mRNA-1273) by Boston-based biotechnology company Moderna.

Experts say nucleic acid vaccines have the advantage of a shorter development and production cycle, as they use a copy of the genetic code of the pathogen without needing live virus samples. But neither RNA or DNA-based vaccines have ever been approved for use in humans before.

China's Ad5-nCoV is also a promising candidate, as the method was used by the same team to successfully develop an Ebola vaccine in 2017.

As the pandemic continues wreaking havoc on many countries, there is a strong chance that the novel coronavirus could return in seasonal cycles. If that is the case, a reliable vaccine is the ultimate solution for the world.

Click to see more real-time statistics on global COVID-19 cases

But no matter which approach is adopted, clinical trials cannot be skipped or hurried so as to ensure the safety and effectiveness of a new vaccine.

Graphics: Jia Jieqiong, Feng Yuan