Editor's note: CGTN's First Voice provides instant commentary on breaking stories. The daily column clarifies emerging issues and better defines the news agenda, offering a Chinese perspective on the latest global events.

Where does the new coronavirus come from? This has been one of the greatest unknowns over the past several months as the world faces a fast spreading pandemic.

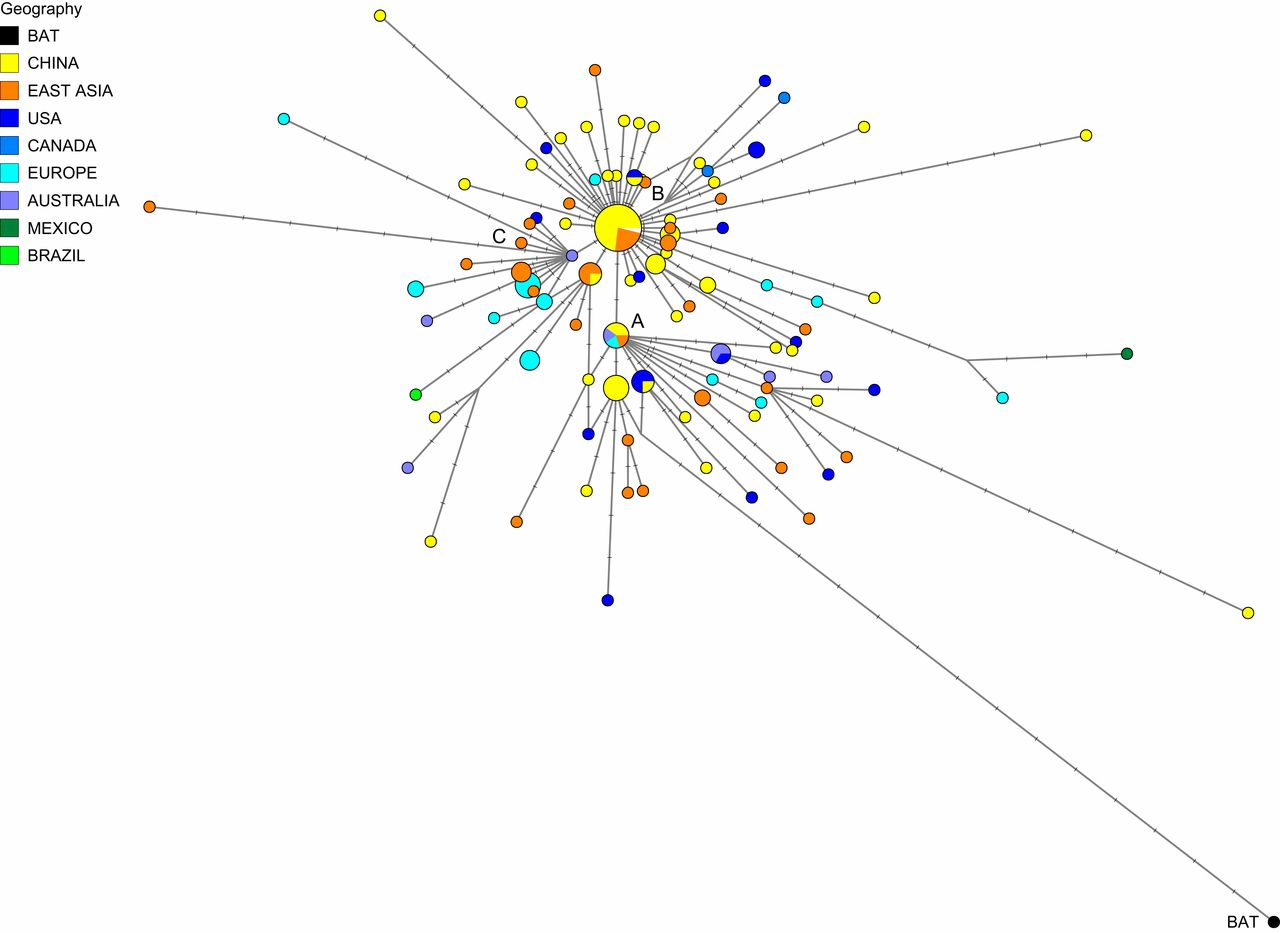

On April 8, a research seems to be bringing the world a step closer to the answer. A group of scientists from the University of Cambridge, the University of Kiel, the German Institute of Forensic Genetics and Fluxus Technology and Lakeside Healthcare mapped out the coronavirus's path of infection around the world. This study found that the earliest known strain of the virus, termed by the scientists as "Type A," is commonly detected in the U.S. and Australia. Type A is discovered to be the "ancestral type according to the bat outgroup coronavirus." The "Type B," which is mostly found in East Asia, is a mutated version of Type A. European nations are currently been hit largely by "Type C," a mutation of Type B.

Based on the research, Type A virus was found on some Americans who've had a history of residency in Wuhan. But, this specific type of coronavirus didn't cause widespread infections in the city. It is the mutated version, the Type B, that was transmitted on a large scale in the city, later to other parts of China and in other Southeast Asian countries.

It needs to be noted here that the study hasn't been peered reviewed nor officially published. Neither, with all the work that has already been done, could the scientists themselves draw a conclusion about the roots of the virus. Even after months of the world's best brain-powers and virologists working on the virus, there are still more unknowns than knowns.

The scientists have tracked the coronavirus's movement. /Peter Forster, Lucy Forster, Colin Renfrew, and Michael Forster /PNAS

The scientists have tracked the coronavirus's movement. /Peter Forster, Lucy Forster, Colin Renfrew, and Michael Forster /PNAS

While the unknown has been an obstacle for health officials and doctors trying to save their patients, it has served as an opportunity for politicians who sought to take advantage of the situation for their political purposes. U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo repeatedly used the term "Wuhan Virus," directly against WHO's guidance of not naming the virus with any particular geographical or national feature.

Senator Tom Cotton published an opinion piece on Fox on April 10. Using the virus as an excuse, the junior senator continues his extreme hardline stance against China by calling on the reader to treat the Communist Party of China "as we would any serious disease," threatening to make China "pay" by sanctioning the country at the World Trade Organization and revoking the country's special trading privileges with the U.S., and accusing the World Health Organization (WHO) officials like Dr. Bruce Aylward as "cronies."

And apparently, the politicization of the virus doesn't escape the scientists' mind. Dr. Peter Forster, the first author of the research mentioned above, responded to a query from the Global Times saying that "I was anticipating that the origin of the virus would be a 'hot potato' after the Chinese-American political dispute." it isn't a stretch to say that the research could potentially give the world a clearer depiction and light the fuse on the dispute.

Even WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has become a target of attacks. The picture is a screenshot from his press conference on April 8, 2020.

Even WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has become a target of attacks. The picture is a screenshot from his press conference on April 8, 2020.

But it is important to remember that scientific research takes time. And Forster's research, though appeared on University of Cambridge's website, still has to prove. The virus is complicated. Robert Redfield, Director of U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, admitted during a hearing before Congress that some of the deaths from previous flus were actually died because of COVID-19.

Even with this as the backdrop, the new information that the United States and Australia has more ancestral type of the virus strain still couldn't lead to a conclusive statement from the scientists about the origin of the disease. It'd be unseemly for the layman to connect the dots between each piece of information before the whole scientific truth is revealed. Politicians, who are very often – or should I say most likely – neither majored in virology nor have hands-on experience with diseases, shouldn't jump ahead either.

"No need to use COVID-19 to score political points … it's like playing with fire," said Dr. Tedros, the Director General of WHO, a day after U.S. President Donald Trump attempted to pin the blame of U.S.' deaths on WHO. There's even less necessity to do so when the flame is already high. Rushing to pin the blame when every piece of new information comes out is a fruitless quest. We've already seen it. Within a couple of weeks, the United States have alienated China and WHO even though the death toll and infections kept rising and it is relying on resources purchased from China and advises from WHO to manage the outbreak. So, the question is: what's the point of doing it in the first place?

According to a Washington Post story, when the Spanish flu ravaged the world, Spain "hated" the nomenclature. As COVID-19 spreads, China has no fond of the term "Chinese Virus." With each new information coming out, it would become increasingly clear where the disease is originally from. But it cannot be denied that, wherever it came from, it is now a global problem. Pinpointing its origination helps the public health officials to better facilitate containment. Politicizing it only hinders the effort.

Script writer: Huang Jiyuan

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)