Editor's note: Sarah Colenbrander is head of Global Programmes for the Coalition For Urban Transitions. Lucy Oates is former research fellow at the University of Leeds. The article reflects the authors' views, and not necessarily those of CGTN.

China has 20 cities with over five million residents. It may be unsurprising, therefore, that so many people had not heard of Wuhan – population 11 million – until it began to dominate international headlines as the epicenter of COVID-19 outbreak in China.

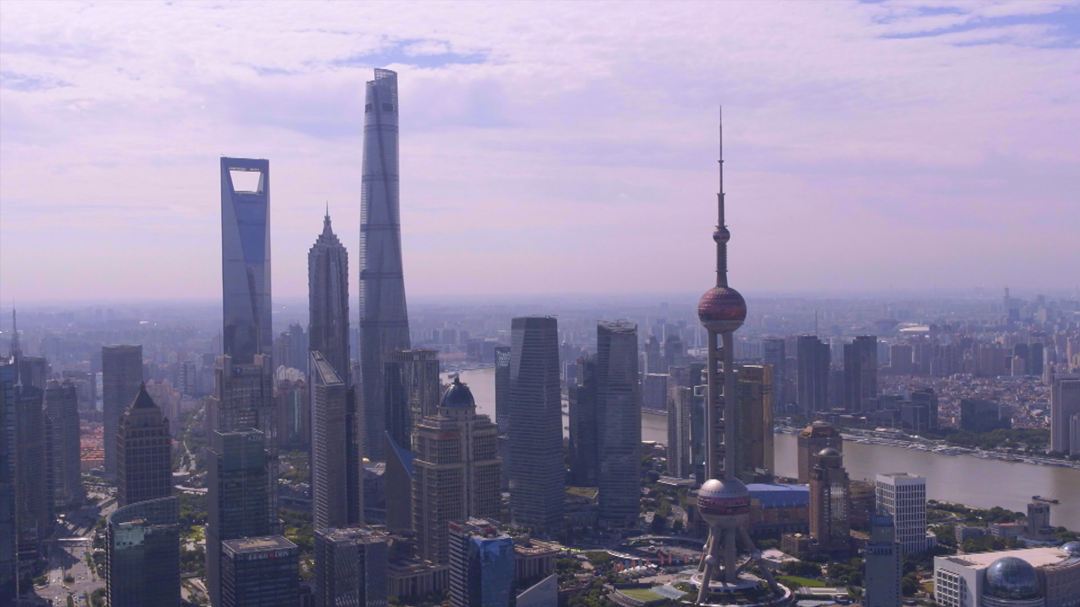

But this is the new normal. The future of China's cities is inextricably tied to the future of the planet. China's cities are already home to over 900 million people – more than the total population of Europe. Over a quarter of the world's manufacturing output is produced in China, much of it exported through immense urban ports such as Guangzhou, Ningbo and Shenzhen. And as the climate emergency looms, decisions made in Chinese cities have a disproportionate impact on global emissions.

Fortunately, many of these cities are leading the charge against global warming. New research from the University of Leeds for the Coalition for Urban Transitions documents the achievements of these frontrunning local governments across China.

Back in the saddle: lessons from Shanghai

Dockless bike-sharing schemes have grown rapidly, with more than 17 million dockless shared bikes now used across the globe. Shanghai alone has over 1.5 million public dockless bikes – one for every sixteen residents.

Dockless bikes have huge potential to improve public health by encouraging more exercise and improving air quality. A new assessment of over two million bicycle trips shows that bike-sharing in Shanghai reduced fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions by 2.7 percent and 0.9 percent respectively in 2016. They also cut greenhouse gas emissions.

However, the popularity of dockless bikes has waxed and waned in Shanghai. Bikes were often left haphazardly in doorways and sidewalks. The regular bankruptcies of new companies (10 companies bowed out of the market in 2017 alone) led to bicycles being abandoned and vandalized. And without segregated cycle lanes, cyclists were forced to compete with cars and pedestrians – which made them unpopular with everyone.

Shanghai's great innovation was to regulate dockless bike-sharing schemes, working closely with the Ministry of Transport. The city government now requires companies to register bikes with the police and provide insurance for users. It has also established electronic geofencing systems so that people park their bikes safely and conveniently.

Passengers take the subway line in Wuhan in central China's Hubei Province on Wednesday, April 1, 2020. /AP

Passengers take the subway line in Wuhan in central China's Hubei Province on Wednesday, April 1, 2020. /AP

Electrifying transport: Lessons from Shenzhen

To avoid climate crisis, most of the world's transport needs to be electrified by 2050. Today, China is home to nearly half of all electric passenger cars and over 99 percent of electric buses. In 2018, Shenzhen became the first city in the world to electrify its entire public bus fleet. Only months later, its taxi fleet followed suit.

China's dominance of this market rests on a national program, launched in 2001, to improve batteries, charging infrastructure and other key elements of the electric vehicle ecosystem.

Shenzhen was one of 10 Chinese cities with a mandate to deploy electric vehicles. The city government introduced subsidies for charging infrastructure and lower electricity tariffs for charging operators, which drove the construction of 40,000 charging stations.

Shenzhen is already a quieter, cleaner city. Its 16,000 buses move almost soundlessly through the streets. Its air quality is better than at any other point in the last decade. And the shift to electric buses and taxis has cut the city's annual emissions by about as much as taking half a million cars off the road would do. Shenzhen offers inspiration to cities looking at expanding electric buses, from Izmir to London to Santiago.

Working with nature: lessons from Wuhan

Wuhan is a pioneer in nature-based solutions – that is, the use of ecological systems rather than concrete and steel to solve problems from air pollution, to flooding, to stress.

Over the last seven years, the local government has rolled out hundreds of projects to conserve and enhance nature: Gardens, parks, wetlands, artificial lakes, green roofs, permeable pavements, canals and rainwater harvest systems have been installed throughout the city. Thirty-eight square kilometres – more than ten times the size of Central Park in New York – have been carved out to provide green spaces for people to enjoy during dry weather, and to absorb floodwaters when it rains.

Wuhan's approach to managing floodwaters was more than 4 billion yuan (almost 600 million U.S. dollars) cheaper than upgrading the city's drainage system.

These numbers don't take account of benefits such as improved air quality, richer biodiversity, higher land values and better quality of life. Nor do they measure the significant greenhouse gas reductions associated with avoiding steel and cement, or the 724 tons of carbon dioxide sequestered every year by Wuhan's new vegetation. That's enough to offset the carbon footprints of nearly a hundred Chinese citizens, all while providing a cleaner, greener city to enjoy – once Wuhan's population emerges from lockdown.

Seizing China's urban opportunity

2020 is a critical year. The Paris Agreement on Climate Change encourages countries to submit a new climate commitment every five years, with the next round of pledges due at COP26. Many of the world's largest emitters – Brazil, Saudi Arabia, the U.S. – have already made it clear that they do not intend to set higher targets. China's leadership is more important than ever.

The Chinese government is on track to meet its Paris Agreement targets and peak emissions in 2030. This year, it could go further by pledging to support its cities to peak emissions even earlier. Many of its provincial and city governments have already made such a pledge; indeed, a handful including Beijing, Ningbo and Yantai are projected to peak in 2020.

This is a crucial moment for China. Internally, it is grappling with an epidemic; externally, it is recovering from severe trade shocks. But runaway global warming will only exacerbate the economic and social challenges facing the country. Bold action to decarbonize its cities would help to sustain global climate momentum, as well as tackling domestic priorities such as air pollution, traffic congestion and public health.

(If you want to contribute and have specific expertise, please contact us at opinions@cgtn.com.)