"What happens when COVID-19 is introduced to the community?" a Maori doctor asked recently.

While New Zealand has won praise for taking quick action against the epidemic and limiting its spread, one part of the population is more worried than the rest: the Maori and Pacific Islanders' communities.

Maori make up 16.5 percent of New Zealand's 4.7 million people and Pacific Islanders contribute another 8.1 percent. So far, there have been about 1,400 confirmed and probable cases of COVID-19 nationwide and 11 deaths. Of these, 120 have been Maori and 64 Pacific Islanders.

But experts and health officials have warned the number of cases could explode if the virus reaches deep into these communities.

Poverty among Indigenous groups is rife, unemployment among Maori is twice the national rate and overcrowding is a serious problem, with Maori four times more likely than New Zealanders of European descent to live in a crowded home, and Pacific Islanders eight times more likely, according to a 2018 report by the national data agency Stats NZ.

Maori and Pacific Islanders also suffer more often from chronic illnesses and respiratory diseases, making them more vulnerable to COVID-19, which attacks the lungs.

Making things worse, many live in remote communities hours from the closest hospital. And those who need medical care are already struggling to get it.

"People are being told that their health needs aren't COVID-19-related and they aren't a priority at this time. This is worrying for us as many Maori have medical conditions and long term illnesses and this is exacerbated by COVID-19 and they actually need good care now," one doctor, Rawiri Jansen, told Radio New Zealand (RNZ).

New Zealand Minister of Maori Development Nanaia Mahuta, left, and Australian Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt, right, pose after signing the Indigenous Collaboration Arrangement in Sydney, Australia, February 28, 2020. /AP

New Zealand Minister of Maori Development Nanaia Mahuta, left, and Australian Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt, right, pose after signing the Indigenous Collaboration Arrangement in Sydney, Australia, February 28, 2020. /AP

As an example of how bad things could get, community representatives have pointed to past epidemics, including the 1918 Spanish flu, which saw Maori die at a rate eight times higher than Pākehā – the Maori term for New Zealand Europeans.

In an open letter to Health Minister David Clark last week, Rawiri Taonui, a prominent writer and scholar of indigenous studies, added that "Maori died at six times the rate of Pākehā in the 1957 Asian Flu pandemic, eight times the rate for Pākehā in the 1959 Tuberculosis epidemic, three times the rate during Swine Flu in 2009."

Other countries, same problems

It's not just in New Zealand that Indigenous communities have been ringing the alarm about COVID-19.

Native Americans in the U.S., Aboriginal people in Australia and Canada's First Nations could be equally vulnerable to the pandemic, with social conditions similar to the Maori: from poverty and unemployment to overcrowded dwellings and chronic health problems.

In some cases, even access to clean running water is an issue, rendering simple precautions such as frequent hand washing difficult. The custom of having several generations live under the same roof also clashes with the idea of isolating the elderly, who run a higher risk of falling ill. Food insecurity and substance abuse, from tobacco to alcohol and drugs, further exacerbate existing problems.

In the U.S., life expectancy among the estimated 5.2 million American Indians and Alaska Natives is already 5.5 years less than the national average, and they frequently suffer from chronic liver disease, diabetes and respiratory disease, according to the Indian Health Service (IHS), which has blamed "disproportionate poverty, discrimination in the delivery of health services, and cultural differences" as well as "broad quality of life issues rooted in economic adversity and poor social conditions."

Members of the Aboriginal community rally on World's Indigenous Peoples Day in Sydney, Australia, August 9, 2018. /AP

Members of the Aboriginal community rally on World's Indigenous Peoples Day in Sydney, Australia, August 9, 2018. /AP

As of April 14, the IHS had recorded over 1,200 positive cases among tribal populations, but it warned the real number was likely much higher. The Navajo Nation, which spans three states, has seen 1,042 cases and 41 deaths, according to its health department. Worryingly, New Mexico this week reported that 36 percent of all positive cases were Native Americans.

In Canada, the epidemic has not hit Indigenous communities very hard yet, in part because they tend to be located far from cities. But, "no one should take great comfort in the fact there have been few cases to date," Minister for Indigenous Services Marc Miller warned last week. And the isolation of these communities also means any outbreak could have dire consequences, with limited access to proper medical care, let alone the kind of intensive care needed in this case, nearby.

In Australia, almost 39 percent of the country's 798,000 Indigenous Australians live in "outer regional" or remote areas, and community groups have warned that the effect of the virus spreading there would be "catastrophic."

National solutions

To help tackle the pandemic, New Zealand promised 56 million New Zealand dollars (33.6 million U.S. dollars) to Maori communities, with more than half of that earmarked as health funding. Canada said it would distribute 305 million Canadian dollars (217 million U.S. dollars) to its Indigenous population.

The U.S. pledged at least 40 million U.S. dollars in emergency funding to Native Americans. And the Australian government earlier this month announced it would make 123 million Australian dollars (78 million U.S. dollars) available over two years to help Indigenous businesses and social support programs, including meal deliveries.

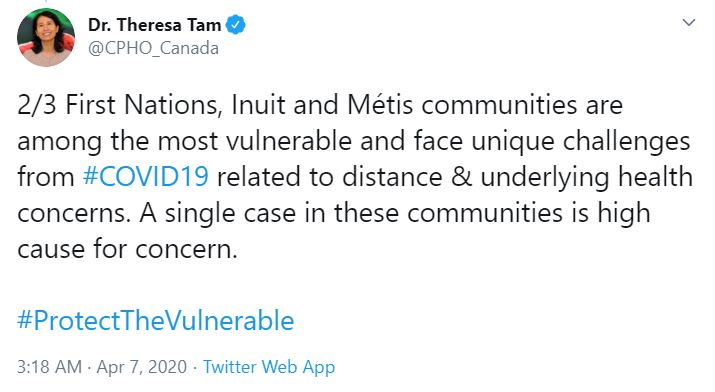

Tweet by Canada's chief public health officer Theresa Tam. /CGTN screenshot

Tweet by Canada's chief public health officer Theresa Tam. /CGTN screenshot

For community representatives, this is not enough. One of the main complaints is that not enough testing is being done among their people.

"There is trepidation that mainstream test sites do not always engage well with Maori, that Maori are being disproportionately declined tests and that adequate numbers of Maori are not being tested," Rawiri Taonui wrote in his open letter.

On Thursday, Australia announced a 3.3-million-Australian-dollar (2.1-million-U.S.-dollar) plan to set up 83 testing sites in Indigenous communities by mid-May "to ensure no community is more than two to three hours' drive from a testing facility," said Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt.

In Canada, a petition by First Nations representatives and health professionals asking the government for rapid test kits and ventilators as well as field hospitals and temporary housing to quarantine those who are sick, has already garnered over 16,000 signatures.

Grassroots efforts

Instead of waiting for action from above, Indigenous groups have taken matters into their own hands.

A Facebook post showing Maori Party candidate Rawiri Waititi manning a checkpoint at Cape Runaway, New Zealand. /CGTN screenshot

A Facebook post showing Maori Party candidate Rawiri Waititi manning a checkpoint at Cape Runaway, New Zealand. /CGTN screenshot

Several Maori communities in New Zealand have set up checkpoints on major roads to prevent outsiders coming into their towns. Maori doctors, nurses and public health experts also created the National Maori Pandemic Group early on, with a website and social media presence to share information and practical tips specially tailored for their communities.

Australian Aboriginal groups have reportedly been trying to move their elders – who play a key role in their society, passing down culture, language and identity – away from their community and into so-called "safe areas" where they are less likely to catch the disease.

And in the U.S., an initiative launched by a few Navajo women has been delivering food packages and water in the community, helped by a GoFundMe page that has already raised over 720,000 U.S. dollars.

"We are vigilant in playing our part to defeat the dangerous pandemic that threatens to take our mothers and fathers and brothers and sisters," Rawiri Taonui wrote in his open letter.

But fear of widespread contagion remains. And for many, it is now up to governments to deliver on funding and equipment.

(Cover image: Aboriginal Australians sit on the side of the street in downtown Wadeye in the Northern Territory of Australia, May 29, 2009. /AP)