Hungry for days, scores of snakes lazily slither at a farm in a remote Sanchang village in Anhui Province, occasionally hissing to signal their breeder Wang Yang to feed them.

For decades, China promoted captive breeding of wild animals, including bamboo rats, wild boar, snakes, civet cats, frogs and sika deer. Most of them were bred for eating, and their fur was used as clothing material. Only a small portion of them were kept as pets and used in traditional Chinese medicines. But a crackdown on the 50 billion U.S. dollar annual trade has restricted sale, purchase and eating of banned wild animals, leaving wildlife farmers in a lurch.

Legislative changes to enforce the ban, likely to be finalized by May, are aimed at preventing viral outbreaks, like the ongoing novel coronavirus pandemic. Similar actions were mooted after the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2002 when civet cats were linked to the outbreak.

Captive-bred animals starving, farmers facing losses

"Snake farming had been our livelihood for decades. Today, we are clueless about whether to slaughter and bury them or let them starve to death as selling snake meat is now illegal," lamented Wang.

"Government's action has disrupted availability of feed for snakes," he added, since it is now illegal for feed companies to sell to captive breeders.

Wildlife trade employs more than 14 million people in the country. In Wang's village, more than 70 snake breeders are reeling under similar crises. The situation is equally alarming for bamboo rats, a constant nibbler.

Around 10,000 bamboo rats are likely to starve to death in the farm of Liang Qiubo, a leading captive breeder, employing over 200 locals in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. "It has been three months since the restriction, now I can't afford to feed them," said Liang. His farm is likely to suffer a loss of 10 million yuan.

Liang and the bamboo rats he breeds. /Photo courtesy of Liang

Liang and the bamboo rats he breeds. /Photo courtesy of Liang

Wildlife farmers would also require official permission from the local forestry authority before culling or disposing of their stock.

"We can't even release these animals from our farms. Imagine the situation when hundreds of snakes and bamboo rats are released," they said.

Since bamboo rats are easy to raise – they eat little and have a robust immune system – a poor farmer with more than 200 bamboo rats can earn around 40,000 yuan annually, said He Chunfen from Guilin city in Guangxi.

He sells most of his bamboo rats to China's Guangdong, Sichuan and Yunnan province, but now because of the crackdown, he is losing around 40,000 to 50,000 yuan every month. To keep his rats alive, he has changed their diet to rice mixed with corn from bamboo shoots and roots.

Clueless about wildlife and viral outbreak link

Lured by decent profit and unable to decipher the complex science behind wildlife trade and viral outbreaks, farmers refuse to believe their farms could become a breeding ground for viruses.

"I have been in close contact with bamboo rats for 15 years, they have bitten me a few times… But never did I fall ill," Liang said.

He regularly sold his rats to the wet market in Guangdong province, where dozens of live wild animals crammed into cages are sold in bulk. Brimming with confidence, he said: "There had been no incident of any disease in the market."

According to leading researchers, nearly 70 percent of emerging infectious diseases in humans came from zoonotic origin. The novel coronavirus originated from bats, which possibly found pangolin as an intermediary host before jumping on to humans.

A close-up photo of the bamboo rat Liang raised. /Photo courtesy of Liang

A close-up photo of the bamboo rat Liang raised. /Photo courtesy of Liang

Even in the case of Ebola, SARS and MERS, the viruses came from bats and found a host and infected humans. According to recent researches, more than 1.7 million viruses with the potential to infect humans still exist in wildlife.

Some animals can still be farmed for meat and fur

In late January, when the government announced a ban on the wildlife trade, Nine Deer, a firm that breeds sika deer were equally concerned about the stock.

But a few days later, local authorities confirmed sika deer is not on the draft list of animals banned for captive breeding. The majestic deer raised by the company were saved but such revisions took many by surprise.

The list released on April 9, included animals like reindeer, alpacas, guinea fowls, ostriches and emus, which can be farmed for meat. Silver fox, arctic fox, and raccoon dog farming have been allowed for the production of fur, which defeats the purpose of wildlife ban to prevent viral outbreaks.

"It's not a complete ban on wildlife trade," Liu Jinmei, General Counsel of Friends of Nature, told CGTN. The policy only bans illegal trade, consumption of wild animals listed by the government. Still, it allows the use of wild animals for medicinal use and fur production.

A man wearing a protective face mask walks by a poster promoting to protect wildlife animals, Beijing, March 11, 2020. /AP

A man wearing a protective face mask walks by a poster promoting to protect wildlife animals, Beijing, March 11, 2020. /AP

"The government is cautious about excluding wildlife animals from the ban, especially terrestrial animals," said Liu. Whether or not an animal can be excluded should focus on: consumption rate of wild animals, risk of outbreaks, and technology available for safe meat production, she suggested.

Equally intriguing is the non-inclusion of pangolins – strongly linked to the novel coronavirus pandemic – leopards and a few other iconic animals.

Aron White, a wildlife campaigner with Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), explains lawmakers are focusing on animals used for eating rather than altogether ending the trade in protected species.

"Trade in pangolin scales, leopard bones, and captive-bred tiger skins have not been banned," he told CGTN. "Lawmakers should ban all trade in all species that are threatened by trade and launch an evidence-based behavior change campaign to end persistent demand among consumers who aren't dissuaded by the ban."

Agriculture, chicken, pork production: no more attractive

A few provincial governments have announced compensation but only to those firms having a permit for wildlife farming. A large number of farmers claim, only two percent of firms have such a document.

While the government's proposed wildlife ban is already in effect, a few provinces have started providing subsidy to wildlife farmers to switch over to an alternate livelihood.

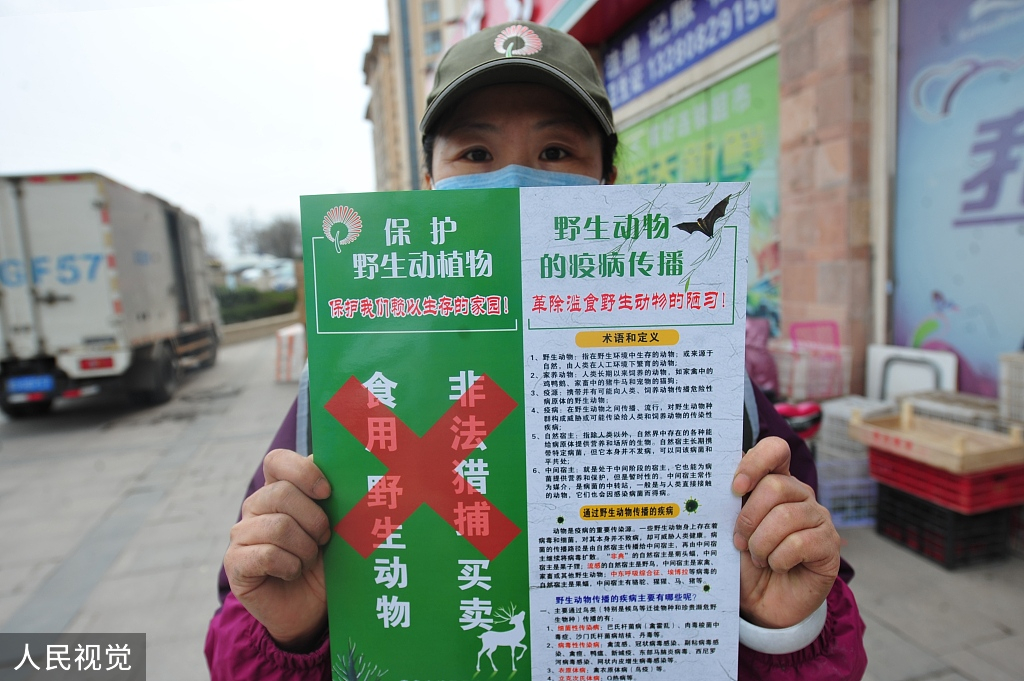

A poster that says the consumption of wildlife animals and the illegal trade and hunting of wildlife animals are prohibited, Qingdao, China. /VCG

A poster that says the consumption of wildlife animals and the illegal trade and hunting of wildlife animals are prohibited, Qingdao, China. /VCG

Since wildlife farming requires a large patch of land, Ganzhou City of southern China's Jiangxi province is offering loans up to 300,000 yuan to help wildlife breeders switch over to agriculture. Farmers can also raise chicken or pigs.

Authorities are motivating them to produce Camellia oleifera plant, a good source of edible oil. Farmers below the poverty line are eligible for an interest-free loan.

But some farmers are hesitant.

"Of course, I can turn to raise pigs, but with the risk of African Swine Fever, if I lose one pig, I would lose more than one thousand yuan," said He. "In comparison, the risk in bamboo rat raising business is much lower."

Pork, chicken and poultry sector is already too competitive, and wildlife farmers are not eager to invest in the industry, said Liang, a captive breeder of bamboo rats.

Experts believe that a large number of captive breeders desperately looking for a new occupation might come as an opportunity in disguise for China.

"The government had redeployed people in the past, such as when it banned logging, and perhaps farmers should be assisted in switching to domestic animal or crop production," Peter Knights, CEO of WildAid, an environmental organization told CGTN.

"Obviously, this may involve some cost in the short term, but little in comparison to the economic damage caused by a pandemic," he suggested.

(Cover image designed by CGTN's Qu Bo)