As the deadline (May 9) for the Iraqi prime minister-designate to form a government approaches, all eyes are now on the 53-year-old intelligence chief's next moves. Mustafa al-Kadhimi, the third candidate tasked with taking the country out of its months-long political stalemate, seems to be on the right path to overcome seemingly insurmountable hurdles.

On Wednesday, Kadhimi submitted his prospective government's program to parliament, but whether it will be approved by the highly fractured legislature remains largely unknown.

Previously a prominent opposition figure during Saddam Hussein's rule, Kadhimi was appointed as the head of the Iraqi National Intelligence Service in 2016. He has presided over much of the battle against ISIL and his agency also played a key role in the hunt for the notorious armed group's leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.

Unlike the two previous candidates, Kadhimi appears to garner broad support from across the political spectrum. Some of the most powerful Shiite parties, along with other Sunni and Kurdish factions, have all come out to signal their support for the independent candidate. On top of that, the vote of confidence extended by the United States, the United Arab Emirates, and Iran has also cleared the way for his success.

"The first candidate Mohammed Tawfiq Allawi was considered as too subservient to Iran and met opposition even inside the Shiite camp," Meir Litvak, chair of the Department of Middle Eastern and African History at Tel Aviv University, told CGTN. "As for Adnan al-Zurfi, the second candidate, he was associated too much as a pro-American and Iran exerted very heavy pressure against him."

Yet the ideal scenario where Kadhimi does secure a cabinet lineup that is acceptable to most parties barely offers any comfort to the protesting Iraqis.

Forming a government in Iraq has never been easy. It's important to note that outgoing Prime Minister Abdul al-Mahdi took almost a year to complete the cabinet allocations after assuming office.

As a relatively young, yet overly flawed democracy, the nascent republic has suffered multiple political crises throughout its existence. Causes for each of these could be manifold, but they never escape a dominant political arrangement that has been shaping Iraq's political landscape since 2005.

The muhasasa, a sectarian quota system that organizes Iraqi politics along confessional lines, was initially intended to include Iraq's diverse ethno-sectarian groups for proportional government participation. But as the mechanism itself also leaves room for manipulation by self-serving politicians while inadvertently deepening sectarian divides, it has become a breeding ground for a slew of perennial woes disastrously plaguing the country.

Featuring much of Iraq's last 17 years was a mixture of deeply entrenched corruption, rampant sectarian violence and constant political instability. Over the years, Iraqis have been attributing the country's unabated hardships to the muhasasa and the public demand for its removal only grows stronger.

Coinciding with Iraqis' rejection of the Muhasasa is a wave of civil unrest that has lasted more than half a year with no sign of ending despite the coronavirus pandemic. While the occupation of public squares across the country has subsequently unseated a prime minister, Baghdad has done little to address the protesting crowds' key demand.

Anti-government protests in Baghdad, Iraq, November 14, 2019. /Reuters

Anti-government protests in Baghdad, Iraq, November 14, 2019. /Reuters

Absent in political elites' intention to overhaul the system is their reluctance to give up the muhasasa-stemmed privileges. As this process entitles them to govern based on consensus and informal agreements, the diverse political blocs all have a say in the selection of ministers and other high-ranking positions of the state apparatus. With parties wading into the selection process usually comes a raft of top officials representing sectarian, partisan interests and thus devoid of the necessary expertise to govern, as was the case in almost all previous governments.

While former heads of government, including Abdul al-Mahdi who still serves as caretaker premier, did endeavor to appoint independent technocrats as ministers, such attempts were only to prove futile as the rebellion by parties was too strong.

"It is always a game of who would grab more power, and therefore too many politicians benefit from the system," Litvak said.

Allawi, the first prime minister-designate, received the same fate when he insisted on filling the government with skilled experts.

It is tempting to see whose names were nominated at Kadhimi's discretion, but analysts have already cast doubt on the odds of his list representing a fundamental breakaway from the current cabinet makeup.

Several Iraqi lawmakers told Rudaw, an Iraqi Kurdistan-based news outlet, that Kadhimi's current selections have been pushed through by political parties for the sake of their own interests, rather than being chosen for their expertise.

"The names in Kadhimi's cabinet list have come about through pressure from some political parties in the Kurdistan Region, some Sunni political parties, and some Shiite parties," one MP said.

On Wednesday, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called on Iraqi leaders to "put aside the sectarian quota system and make compromises that lead to government formation for the good of the Iraqi people."

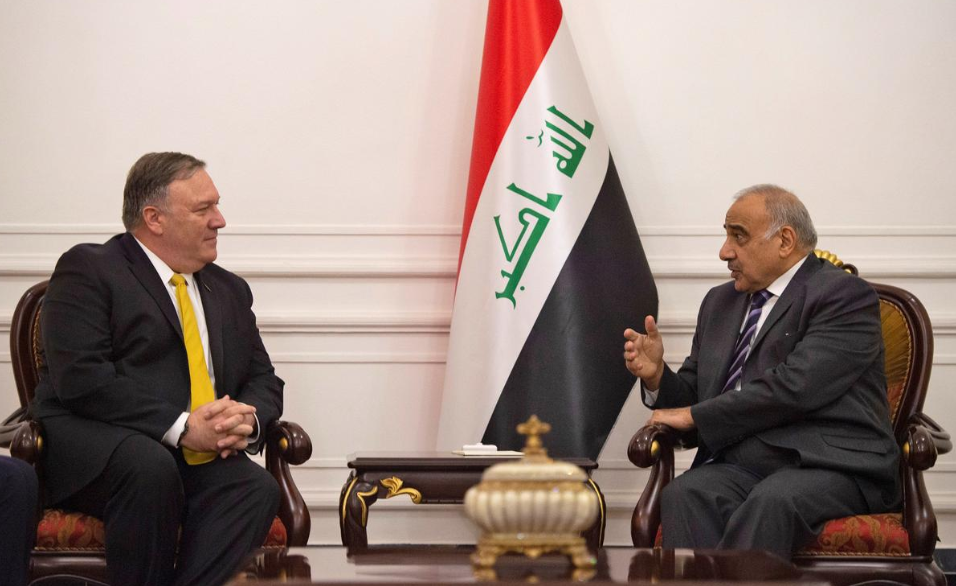

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo talks with Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi in Baghdad, Iraq, January 9, 2019. /Reuters

U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo talks with Iraqi Prime Minister Adel Abdul-Mahdi in Baghdad, Iraq, January 9, 2019. /Reuters

Whether Pompeo's message will have any real impact on Baghdad is unclear, but the enduring political crisis and uncertainties over its future trajectory have surely overshadowed the urgency to overhaul a principal arrangement that enjoys many politicians' silent support.

For political leaders to actually mull the idea of abandoning the system is a taboo that could amount to political suicide, Litvak said. It is exactly this arrangement that they must rely on to secure a complete, though potentially untenable, government. Otherwise, they risk being ousted by a vote of no confidence.

Determination to discard the muhasasa is not completely absent in the political realm, but promises and stated resolve eventually succumbed to the daunting obstacles and thus failed to translate into concrete actions. Indicative of these repetitive cycles is a palpable quandary that has strangled the prospect of any meaningful reform.

So far, none of the three prime ministers-designate has offered a solution that could ultimately fulfill the protesters' primary demand.

(Cover image: Iraqi intelligence chief Mustafa al-Kadhimi speaks during a news conference. /Reuters)