Lately, for once, Malaysians have found a topic to unite them across racial and political divisions: their dislike of the Rohingya ethnic group who have fled Myanmar.

"Send them back." "As anak (children of) Malaysia, we are united and will force Rohingya to leave our country." These are just a sample of some of the less offensive posts.

Malaysia's security minister urges Malaysians to stay calm. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

Malaysia's security minister urges Malaysians to stay calm. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

Malaysia's navy revealed it has been lately pushing boats crammed with Rohingya back out to the sea when they've been intercepted while approaching Malaysian waters, though it has taken in some who made it to land.

Malaysians widely supported the move.

NGOs and groups like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have warned Malaysia of the dangers. One boat ended up adrift for weeks and by the time the Bangladeshi coast guard intercepted it, dozens of people on board had died.

Yusof Ali took a perilous boat journey to get to Malaysia and knows how real the danger is. He now works on a construction site outside the capital.

Yusof Ali says dozens of people died on the boat he was on. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

Yusof Ali says dozens of people died on the boat he was on. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

"We were in a boat at sea for a month," he says.

"We got food and water just once a day. We were beaten for very little reason, even asking to relieve ourselves. Around 70 people died on the journey."

Some 100,000 Rohingya in Malaysia are registered with the UNHCR. Tens of thousands more have yet to be registered.

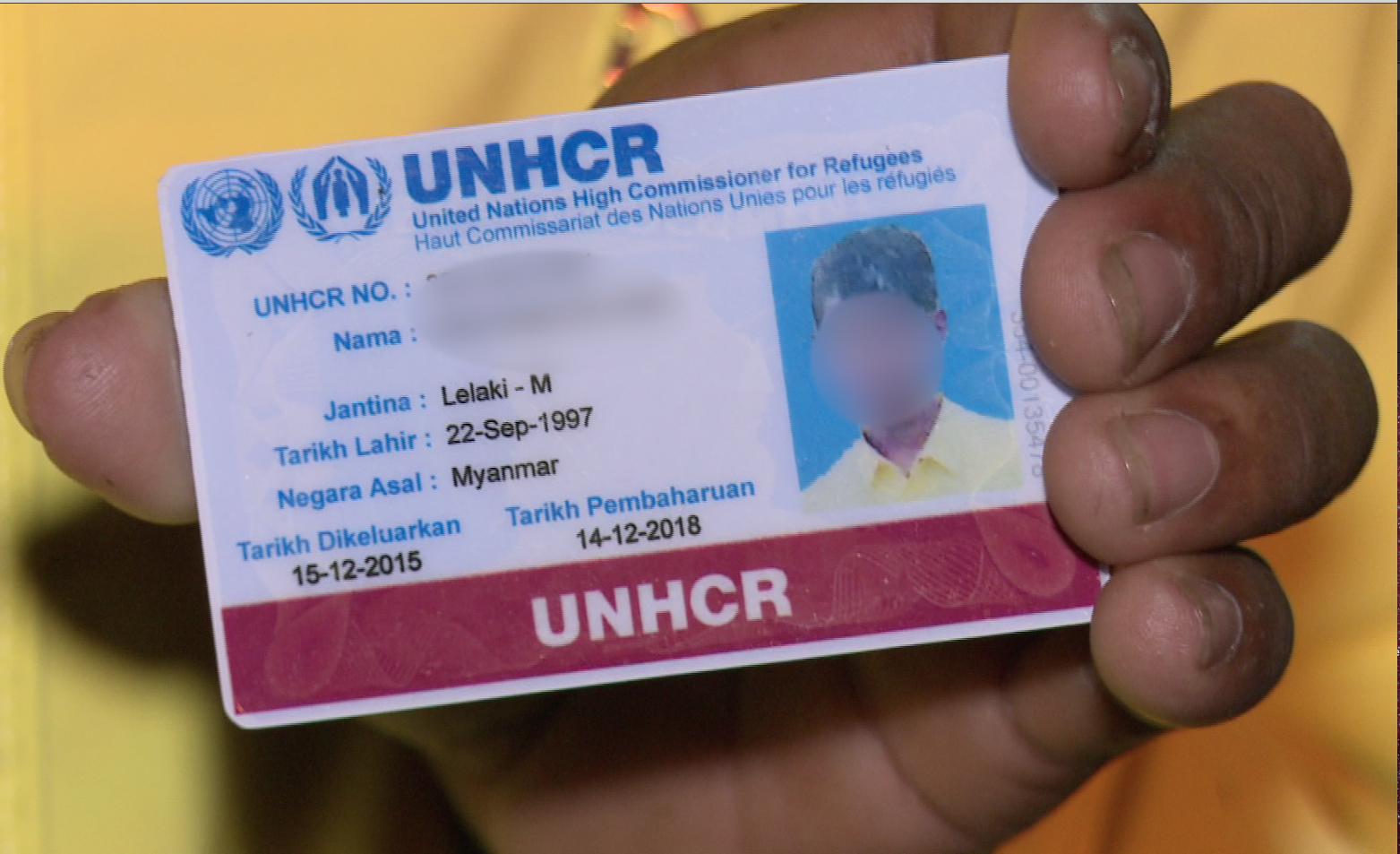

But even those registered with the UNHCR as refugees have few rights in Malaysia since the country has not signed the UN's refugee convention.

The country's Home Minister Hamzah Zainudin this week described the Rohingya as "illegal immigrants with UNHCR cards."

Malaysia doesn't recognize refugees, even with UNHCR cards. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

Malaysia doesn't recognize refugees, even with UNHCR cards. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

This is only likely to fuel the rampant online vilification of the Rohingya that appears to have been sparked by people's frustration over the restrictions imposed to control the spread of COVID-19, and fanned by much fake or misleading news.

False reports have been circulating that Rohingya receive generous daily cash allowances from the UNHCR in excess of the aid poor Malaysians are getting from the government.

A video and statements falsely linked to a local Rohingya activist demanding that Malaysia's government grant the Rohingya citizenship pushed Malaysians into a frenzy.

Refugee children cannot attend state schools. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

Refugee children cannot attend state schools. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

Online petitions calling for Malaysia to withhold even basic food aid to Rohingya in areas under strict quarantine and calling to expel the Rohingya quickly got tens of thousands of signatures, crossing all of Malaysia's racial lines.

Twenty-eight year old Hasnah Hussin is a Rohingya refugee born and raised in Malaysia. She took a break from organizing food aid for the needy from all races to talk with CGTN.

"Honestly, growing up in Malaysia I did face some discrimination. But I have never seen this kind of extreme reaction. I really hope it is because of the COVID-19 outbreak and people are frustrated."

Hasnah Hussin has never seen so much anger toward her community. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

Hasnah Hussin has never seen so much anger toward her community. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

Malaysia's senior minister responsible for security, Ismail Sabri Yaakob, noted that the Rohingya have been in the country for many years without serious issues.

"Suddenly, during the movement control order (to control the spread of COVID-19), it became a big issue and this perplexes the police, because there were too many news on social media that incites anger against them."

He urged Malaysians to remain calm to avoid the occurrence of any untoward incidents.

Hasnah said she herself has faced threats lately, and that the entire Rohingya community is on edge.

"They are living in fear because it's not only backlash on social media, they also receive face-to-face threats from the locals. Suddenly there is all this backlash because of a few fake news. The whole community is being targeted."

Rohingya and other refugees cannot legally work in Malaysia or send their kids to state schools. Instead they work under the table, in odd jobs, prone to exploitation.

And lately, with all except essential services and businesses shut down, most have lost even the meager incomes they had.

NGOs are helping needy locals as well as refugees. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

NGOs are helping needy locals as well as refugees. Rian Maelzer/CGTN

Local NGOs have stepped in to assist them, also a source of ire for many Malaysians. What the critics don't realize is that most of the NGOs are also providing food for low-income Malaysians who find themselves in dire need.

Hansah feels much more dialogue is needed so that Malaysians can better understand the plight of the Rohingya, and the Rohingya – many if not most of whom are illiterate – can better understand Malaysian culture and expectations.

"I really hope this is temporary," Hasnah says. "We are really grateful to the Malaysian government and the local people."