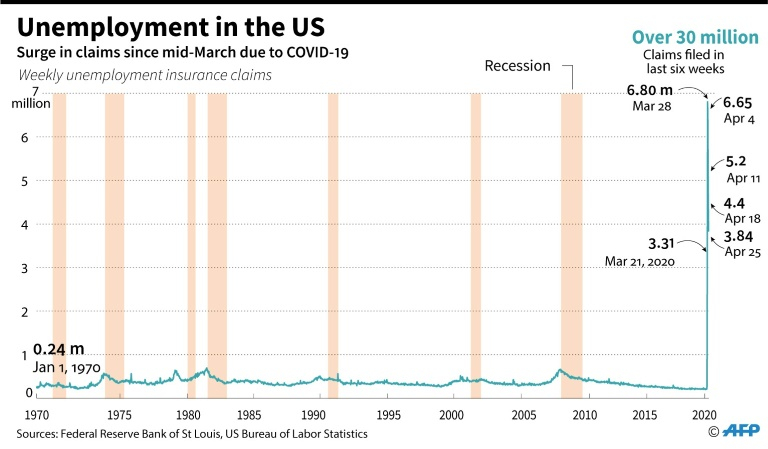

Over 3.1 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits in the week ending May 2, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

The data brings the total claims filed since mid-March, when the coronavirus pandemic forced businesses to close their doors to stop the virus's spread, to 33.5 million, far surpassing the worst of the global financial crisis and reaching levels not seen since the Great Depression last century.

The U.S. government and central bank worked at a stunning pace to rush out aid and financing to workers and businesses to try to prevent a complete economic collapse, but there is a growing fear that the temporary shutdowns imposed to contain the spread of the virus will become permanent for many companies.

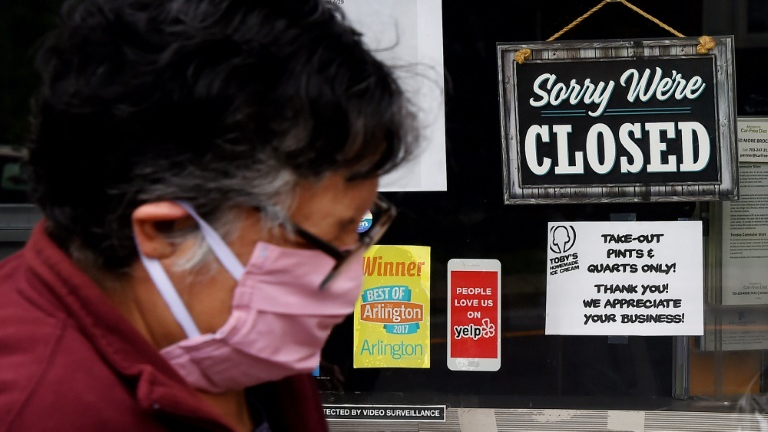

Many businesses forced to close to contain the spread of COVID-19 may not survive. /AFP

Many businesses forced to close to contain the spread of COVID-19 may not survive. /AFP

The coronavirus has infected nearly 1.2 million people in the United States and killed around 70,000, according to a count from Johns Hopkins University, and analysts fear some of the economic damage may be permanent.

"We took the elevator down, but we're going to need to take the stairs back up," Tom Barkin, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, said in a recent speech.

Despite nearly three trillion U.S. dollars in financial aid approved by Congress in March alone and trillions more in liquidity provided by the Federal Reserve, the U.S. economy contracted by 4.8 percent in the first three months of the year -- a period that included only a couple of weeks of the strict business shutdowns.

The second quarter could see the economy plunge by twice that amount.

The worst is yet to come

The data on the jobs market has become so bad so fast that there are no comparisons.

Statisticians in the Labor Department's Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which produces the monthly unemployment report, are using natural disasters as a point of reference.

"The closest that we have in terms of what was in our playbook has been usually hurricanes, because they tend to be large and impact significant periods of time, or areas," BLS Associate Commissioner Julie Hatch Maxfield said.

But even devastating events, like Hurricane Katrina in 2005, were regional -- not national and certainly not global.

The job losses spread from airlines and hotels to restaurants and factories as states ordered lockdowns and then closed schools, sending initial claims for unemployment insurance surging from mid-March, with 20 million posted in the four weeks of April alone.

But those figures could underestimate the true size of the shock, since many people have not been able to file for benefits, and others do not qualify.

The official unemployment rate in March jumped from a historic low of 3.5 percent to 4.4 percent, with 701,000 jobs lost.

But the monthly data, which are separate from the jobless claims reports, are calculated only during the pay period that includes the 12th day of each month, so they too missed the real picture. BLS said the survey of households likely underestimated the jobless rate, which should have been 5.4 percent.

April will be far worse, with some economists projecting jobs losses at 28 million and a 17 percent unemployment rate. And as more businesses report their data, job losses in March are expected to be revised higher as well.

Employment in the private sector alone collapsed 20.2 million last month, U.S. payroll services firm ADP said Wednesday. But ADP acknowledges the data do not present the complete picture.

"Job losses of this scale are unprecedented. The total number of job losses for the month of April alone was more than double the total jobs lost during the Great Recession," said Ahu Yildirmaz, co-head of the ADP Research Institute.

False rebound, slow comeback

Job losses during the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009 totaled 8.6 million and the unemployment rate peaked at 10 percent.

Even among workers who are still employed, many have seen their hours cut.

"It's now clear the economy was in a downdraft much more rapidly than anyone expected," said Diane Swonk, chief economist at Grant Thornton.

The expansive government aid programs mean the U.S. might see a temporary pickup in hiring in May and June, Swonk said.

But if small businesses aren't fully back to normal by July, which depends on consumers feeling safe enough to go back to restaurants and shops, "they're going to have to lay them off again," she said.

(With input from AFP)