Muslims the world over are currently on a spiritual detox, forgoing food and drink from sunup to sundown in their quest to get closer to their creator. But Ramadan can be challenging for worshipers with eating disorders who might find themselves troubled by clashing thoughts and inner turmoil during the holy month.

For a whole month, adherents of Islam embark on some serious soul searching. They're encouraged to look inwards and upwards for enlightenment, take stock of their life and rise above the trammels of everyday desires.

Faith also goes hand in hand with food. On the menu during Ramadan is fasting, a powerful exercise in religiosity.

Passing up meals during daylight hours is a show in compassion and a reminder for people, having experienced the hunger and thirst of the less fortunate, to count their blessings. The act is a test in willpower that requires turning one's focus from worldly pursuits to spiritual needs. By enduring the discomfort caused by deprivation, fasting is also meant to cultivate patience and discipline.

With no food and water for extended periods of time – as many as 18 hours in places like Reykjavik in Iceland this year – observing Ramadan is no small feat to pull off, especially for people with eating disorders.

Testing times

Research on how refraining from food impacts people with eating disorders is hard to come by. A 2018 analysis of three studies on fasting and eating habits and disorders concluded that going nil by mouth "may affect eating behavior in few subjects vulnerable to eating disorders."

The food-centric nature of the occasion makes it tempting but tricky for individuals with unhealthy eating habits.

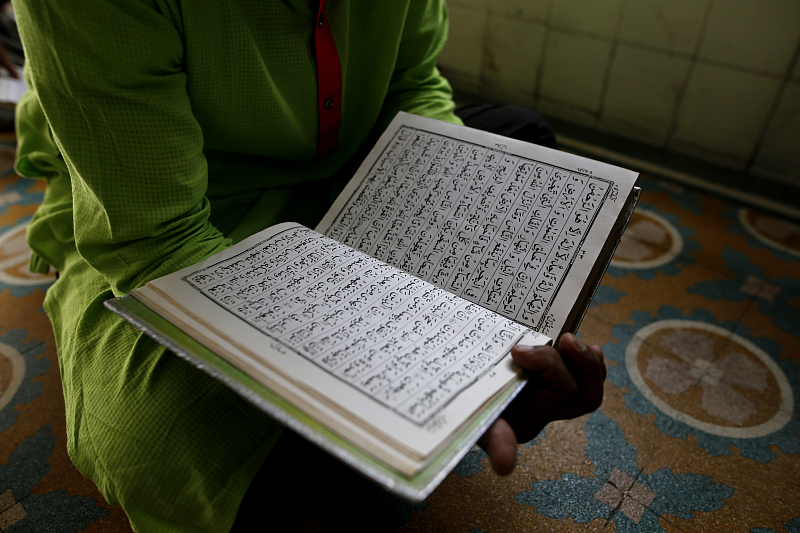

Reading the Quran, the holy book in Islam, is one way to observe Ramadan. /VCG

Reading the Quran, the holy book in Islam, is one way to observe Ramadan. /VCG

"The lack of food, or restricting, or at the end of the day, breaking fast and feasting, could potentially be a trigger for someone with an eating disorder," said Dr. Rania Awaad, a psychiatry professor and director of Muslims and Mental Health Lab at Stanford University.

"The message is always 'eat well, drink a lot of fluids.' For someone with an eating disorder, pushing so much food and drink on them in very limited numbers of hours in the day could be quite difficult," she told CGTN Digital.

Sufferers speak of wrestling between heeding the religious call and giving in to the nagging voice of their disorder, and their caregivers are familiar with the duress and dangerous decisions that could potentially exacerbate their condition.

"Ramadan is really hard for people with ED (eating disorder) because this time is so conflicting. Religiously, it is part of our requirements to fast and when you have a mental health condition, it's hard to put it aside," said Malak Saddy, a Texas-based dietitian who specializes in eating disorders.

Maha Khan knows this struggle all too well. She battled anorexia for over 15 years before recovering. At one of her lowest points, doctors gave the young woman just five weeks to live.

"Before my ED was diagnosed, Ramadan was always the month for me to lose weight. My mind was conditioned from my teenage years to see Ramadan as such," says Khan, who is now an advocate for Muslims with eating disorders.

"After diagnosis, not fasting was horrible and my ED was getting worse. I just wanted Ramadan to be about hunger and starvation," she told CGTN Digital.

Disguised disease

Why Khan and others see an appeal in the holy month isn't all that surprising. Ramadan has the potential to conceal people's fraught relationship with food. It's an ideal excuse to indulge harmful eating patterns without raising suspicions since everyone is skipping repasts during the day and tucking into big plates of food at night.

But as many would tell you, it's a slippery slope. For individuals who are already likely to limit their energy intake, the line between restricted and restrictive diets can become increasingly blurred and fasting could soon give way to deprivation.

Many Muslims spend extra time praying during Ramadan. /VCG

Many Muslims spend extra time praying during Ramadan. /VCG

While the anorexic pick at their food over iftar, the nighttime meal that breaks the fast, bulimic patients "overeat and the urge to purge is extremely elevated," said Saddy. Binge eaters also use abstaining from food during daytime as a justification to overindulge after sunset and a mechanism to ease their guilt the following day.

If the pull of doing without food is self-evident, so are its dangers. No mental health disorder is as life-threatening as the family of eating disorders, and among them, anorexia carries the highest mortality rate. By one estimate, it's four times more fatal than clinical depression and twice as deadly as schizophrenia. The strain of long hours without nourishment on practitioners with disturbed eating habits goes beyond the regular tummy rumbles and hunger pangs to seriously imperil their fragile health state.

"One of my anorexic patients has hypoglycemia and we just stabilized her blood sugar levels. A 12-hour fast could get this girl into a coma," warned Saddy.

And as if things weren't taxing enough already, eating disorder patients have to contend with a deadly pandemic this year as they weigh their options for Ramadan. Amid the uncertainty, anxiety, and stress, experts are sounding the alarm over COVID-19 chipping away at the mental health of millions across the globe, and risking sending individuals already grappling with psychological disorders into a tailspin.

Fast of the heart

Fasting during Ramadan is one of the five pillars of Islam, meaning it's a mandatory duty for every Muslim. Exceptions, however, do exist. Old people, children, pregnant women, and travelers are under no such obligation. The sick are also absolved from the fast – but there's a problem.

Many perceive illness as physical ailments, and mental disorders are oftentimes an afterthought, if at all. This, experts say, invalidates people's struggles and feeds into the feelings of shame and the sense of failing their religious beliefs.

"People are more readily able to see what's directly in front of them. But they can't understand what they can't see," said Awaad, explaining how to make the similarities between the two illnesses more apparent.

"For a person who broke their leg, it's very obvious they're hobbling around and can't get down and perform a prayer. Mental health conditions are more like invisible wounds that [people] can't see. But the person is very much suffering and ailing also."

This is the kind of knowledge that Khan, the London-based mental health advocate, has been trying to spread for years. In 2012, she founded Islam and Eating Disorders, a website to help fellow Muslims combating mental health access scientifically accurate and religiously sound information.

Traditionally, congregational prayers are held in mosques. /VCG

Traditionally, congregational prayers are held in mosques. /VCG

"Going through the treatment, I became so focused on explaining my ED and trying to make sense of it. But there was nothing out there," Khan told CGTN Digital.

So she did what no one before her had done. "I would simply aggregate anything I could find from any source and put it up online."

One memory still vividly stands out. "My eating was very very bad. I remember I went from London in Exeter to see an imam because I wasn't getting an answer [to my question about fasting when mentally struggling]," she recounted.

It was a 300km journey, but Khan got what she was looking for. "If you're ill, you don't fast. You're exempted," the religious leader told her.

"I was able to go back home and put the blog up and say: This is the reference I have," Khan said.

Today, topics on the website run the gamut from nutrition-packed food recipes to explanations of Quranic verses on health and tips for eating disorder patients on how to spend a wholesome Ramadan.

For those who can't abstain from eating and drinking, there are alternatives to recharge their faith.

"Take a fast from using social media, help serve your community through volunteering at food banks or try to manage your anger and temperament," advised Saddy.

During the month of mercy, nourishing the soul comes from the heart, not the mouth.