When the World Health Organization (WHO) declared on January 30 the novel coronavirus outbreak "a public health emergency of international concern" (PHEIC), most of the world thought the virus was China's problem.

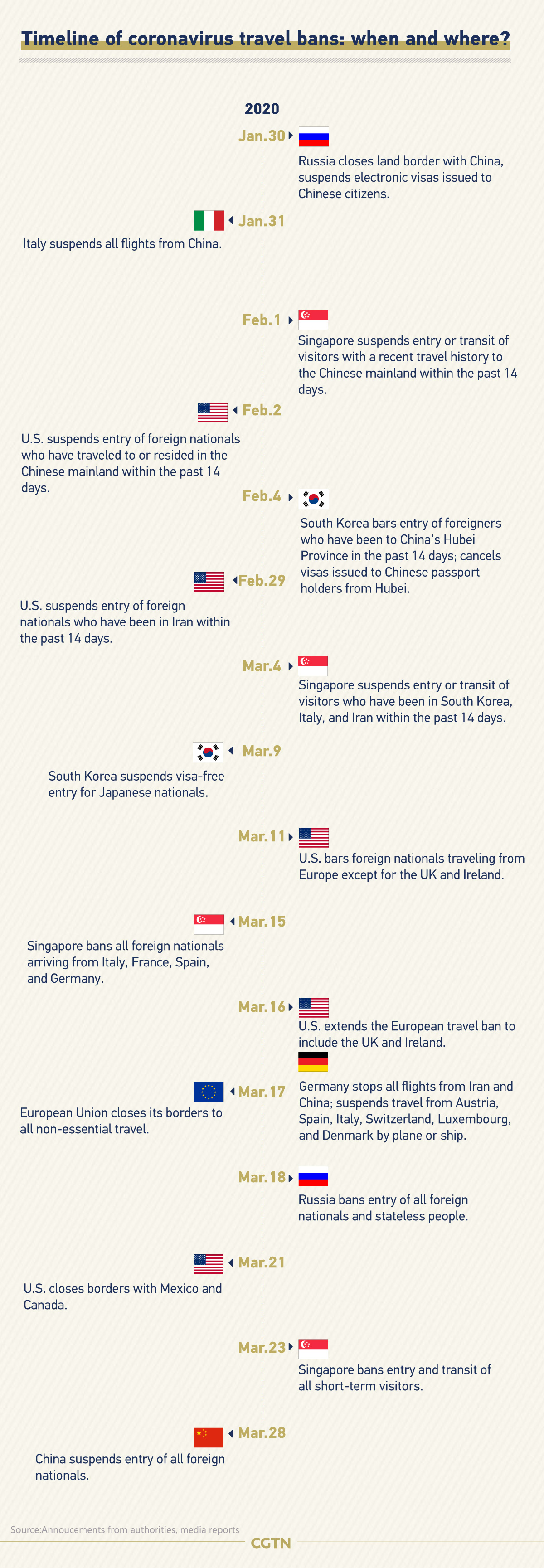

There were less than 100 cases outside China at the time, and 62 countries had already imposed travel restrictions on Chinese citizens. As the situation evolved, restrictions on cross-border movement did not stop there.

By April, at least 93 percent of the world's population were affected by coronavirus-related travel restrictions, with three billion people living under lockdowns that completely bar foreigners, according to the Pew Research Center. It is safe to say that any damage due to disruptions to international travel has been done.

But what's worse is that border closures didn't do much to prevent a global pandemic, which has killed over 300,000 people and sickened more than four million around the world.

Global health experts have overwhelmingly opposed travel and trade restrictions from the start. In its official recommendation, the WHO says denying entry to travelers coming from affected areas are usually not effective in preventing the importation of cases but may have a significant economic and social impact.

However, most countries flouted the UN health agency's guidance. What transpired in countries hardest hit by COVID-19, despite having implemented strict travel bans in the early days, might be a testament to how well such as prohibition has worked.

'Closed the front door, but left the back door wide open'

When China locked down Wuhan, the early epicenter of coronavirus outbreak, there was already a range of measures such as screening of passengers on arrival, flight cancelations, and travel advisories in dozens of countries with air traffic from China.

Italy and the United States were the first to declare public health emergencies over the virus in late January. Italy imposed a complete travel ban on China, the first EU country to do so, right after two Chinese tourists in Rome tested positive for the virus on January 31. The U.S. began to stop flights from China a few days later at the discretion of airlines but made exemptions for U.S. citizens, residents and family members.

But it wasn't until late February that it became clear the virus had been spreading among the populations in both countries undetected. Both saw exponential increases in infection cases in the following weeks and subsequently became new epicenters in the global pandemic.

To this day, no one understands how the outbreak in Italy's Lombardy region began. However, some scientists speculated the virus came from elsewhere in Europe before the country's flight ban on China.

In the U.S., President Donald Trump has repeatedly cited the China travel ban for fending off criticism over his administration's response to the health crisis, while using the term "Chinese virus" to appease to popular xenophobic sentiments. As new hotspots cropped up, the U.S. broadened its travel ban to more countries, eventually including the whole of Europe amid a full-blown pandemic.

Commenting on Trump's European travel ban in March, Pascal Canfin, chair of the European Parliament's public health committee, said the Italian case proved that banning flights from China didn't work. "So I don't see why it should work from Europe to the U.S.," he said.

The U.S.'s top infectious disease expert Dr. Anthony Fauci had explained that it was too late by the time Trump announced the China ban. By the time he banned Europe, it was even later. Fauci said that there were cases in the community under the radar meant this was no longer a travel-related issue.

"By that time, we had enough cases in our own country that the ability to do the containment slipped … and we saw what happened in New York," Fauci said.

JFK airport in New York, United States, March 24, 2020. /AP

JFK airport in New York, United States, March 24, 2020. /AP

U.S. researchers later found that the country's deadliest outbreak in New York City was seeded there by infected travelers from Europe, not China.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo said in April that "we closed the front door" to the virus with China travel ban but "left the back door wide open." Cuomo reminded Americans again this week that the virus came from Europe in January and February. Yet no one knew about it.

"Everybody was looking at China, and the virus was coming from Europe," the governor said.

Although angered by the U.S. ban, it didn't stop European nations, which have always enjoyed free movement on the continent, from shutting borders between one another.

Most of China's neighbors also acted early in regard to Chinese nationals. Likewise, their real troubles began with either a super-spreading event locally, as in South Korea's Daegu, or an outside source other than China, like the ill-fated Diamond Princess cruise ship in the case of Japan. Russia, where new cases have been rising by over 10,000 since early May, was one of the first to close its land border with China.

Why travel bans failed

An apparent problem with travel bans is that they can never be airtight because, in effect, they only kept out foreign passport holders rather than every single person arriving from an affected area.

This carries the risks of discouraging people from disclosing their travel history, making contact tracing even harder, health experts said. It has also fueled discrimination and stigmatization against certain nationalities.

"Viruses don't carry passports … They certainly don't prefer one country's citizens over another," said Steven Hoffman, professor of global health law and political science at York University who advises governments on pandemics.

Hoffman noted that borders in a globalized society are not as sealed as many like to think, and people who want to travel will find a way to do so. "If we encourage travel through unofficial means, it actually undermines the whole process."

Also, the long incubation period and asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19 means some infected people can cruise through screenings at ports of entry undetected. At the same time, they pass the virus onto more people without realizing it.

The huge workload of enforcing travel restrictions can also take away already-stretched resources from public health measures that have been proven far more effective, experts said, such as developing a vaccine or rapid diagnostic test.

"Although travel restrictions may intuitively seem like the right thing to do, this is not something that WHO usually recommends," said WHO spokesperson Tarik Jasarevic. "This is because of the social disruption they cause and the intensive use of resources required."

The 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR) require countries to base actions that discriminate or disrupt travel and trade on scientific evidence and public health principles. The WHO says travel restrictions are only justified at the beginning of an outbreak to give countries time to prepare for their response.

What set some countries apart afterward was their efforts to keep local COVID-19 cases in check toward late February. That means wide-scale testing, contact tracing, isolation of cases, social distancing, and correct information.

After controlling an initial outbreak, Germany struggles to safely reopen, April 20, 2020. /AP

After controlling an initial outbreak, Germany struggles to safely reopen, April 20, 2020. /AP

A study published in Science magazine shows that the quarantine of Wuhan reduced case importation internationally by nearly 80 percent until mid-February.

Modeling results also indicate that sustained 90 percent travel restrictions to and from the Chinese mainland only modestly affected the epidemic trajectory unless combined with a 50 percent or higher reduction of transmission in the community.

However, even countries that initially succeeded in containing a domestic outbreak, including China, face continued challenges to prevent a resurgence of infections. As seen recently in South Korea, Germany and Singapore – all widely lauded virus-fighting success stories, the relaxing of lockdown and social distancing measures quickly led to an uptick in infection rates and fresh clusters of local cases.

Months into the pandemic, one thing is clear: it has a long past of point for any country to try to stop the virus at its borders. But closed borders are unlikely to be opening back up anytime soon.

(Cover photo and graphic designed by Qu Bo)